User:ToothFairyy123/sandbox

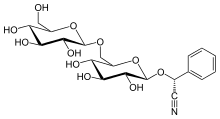

Amygdalin[edit]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(2R)-[β-D-Glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranosyloxy]phenylacetonitrile

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2R)-Phenyl{[(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-({[(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]oxy}methyl)oxan-2-yl]oxy}acetonitrile | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 66856 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| EC Number |

|

| MeSH | Amygdalin |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C20H27NO11 | |

| Molar mass | 457.429 |

| Melting point | 223-226 °C(lit.) |

| H2O: 0.1 g/mL hot, clear to very faintly turbid, colorless | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H302 | |

| P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | A6005 |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds

|

Vicianin, laetrile, prunasin, sambunigrin |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Amygdalin (from Ancient Greek: ἀμυγδαλή amygdalē 'almond') is a naturally occurring chemical compound found in many plants, most notably in the seeds (kernels) of apricots, bitter almonds, apples, peaches, cherries and plums, and in the roots of manioc.

Amygdalin is classified as a cyanogenic glycoside, because each amygdalin molecule includes a nitrile group, which can be released as the toxic cyanide anion by the action of a beta-glucosidase. Eating amygdalin will cause it to release cyanide in the human body, and may lead to cyanide poisoning.[1]

Since the early 1950s, both amygdalin and a chemical derivative named laetrile have been promoted as alternative cancer treatments, often under the misnomer vitamin B17 (neither amygdalin nor laetrile is a vitamin).[2] Scientific study has found them to not only be clinically ineffective in treating cancer, but also potentially toxic or lethal when taken by mouth due to cyanide poisoning.[3] The promotion of laetrile to treat cancer has been described in the medical literature as a canonical example of quackery,[4][5] and as "the slickest, most sophisticated, and certainly the most remunerative cancer quack promotion in medical history".[2]

Chemistry[edit]

Amygdalin is a cyanogenic glycoside derived from the aromatic amino acid phenylalanine. Amygdalin and prunasin are common among plants of the family Rosaceae, particularly the genus Prunus, Poaceae (grasses), Fabaceae (legumes), and in other food plants, including flaxseed and manioc. Within these plants, amygdalin and the enzymes necessary to hydrolyze it are stored in separate locations, and only mix as a result of tissue damage. This provides a natural defense system against insects or animals that might want to eat the plant. Antiherbivory compounds is a defense mechanism against insects or animals that want to eat the plant. However, it is not meant to kill the animal but make the eating process lethal[6]. It is a way to promote animals to eat the fruit instead of the seeds.[7]

Amygdalin is contained in stone fruit kernels, such as almonds, apricot (14 g/kg), peach (6.8 g/kg), and plum (4–17.5 g/kg depending on variety), and also in the seeds of the apple (3 g/kg).[8] Benzaldehyde released from amygdalin provides a bitter flavor. Because of a difference in a recessive gene called Sweet kernal [Sk], much less amygdalin is present in nonbitter (or sweet) almond than bitter almond.[9] In one study, bitter almond amygdalin concentrations ranged from 33 to 54 g/kg depending on variety; semibitter varieties averaged 1 g/kg and sweet varieties averaged 0.063 g/kg with significant variability based on variety and growing region.[10]

For one method of isolating amygdalin, the stones are removed from the fruit and cracked to obtain the kernels, which are dried in the sun or in ovens. The kernels are boiled in ethanol; on evaporation of the solution and the addition of diethyl ether, amygdalin is precipitated as minute white crystals.[11] Natural amygdalin has the (R)-configuration at the chiral phenyl center. Under mild basic conditions, this stereogenic center isomerizes; the (S)-epimer is called neoamygdalin. Although the synthesized version of amygdalin is the (R)-epimer, the stereogenic center attached to the nitrile and phenyl groups easily epimerizes if the manufacturer does not store the compound correctly.[12]

Another method of isolating amygdalin is to grind the apricot seeds into fine powder with 20-100 mesh. Water is added to the fine powder to create a 1:5-20 ratio to obtain a mixture. Finally, the amygdalin is separated using an ultrasonic machine. This method can be used to further decompose amygdalin and remove hydrogen cyanide.[13]

Amygdalin is hydrolyzed by intestinal β-glucosidase (emulsin)[14] and amygdalin beta-glucosidase (amygdalase) to give gentiobiose and L-mandelonitrile. Gentiobiose is further hydrolyzed to give glucose, whereas mandelonitrile (the cyanohydrin of benzaldehyde) decomposes to give benzaldehyde and hydrogen cyanide. Hydrogen cyanide in sufficient quantities (allowable daily intake: ~0.6 mg) causes cyanide poisoning which has a fatal oral dose range of 0.6–1.5 mg/kg of body weight.[15] The cyanide ion attaches to ferric ion on cytochrome oxidase, interrupting the electron transport chain and oxidative metabolism, leading to cellular hypoxia and lactic acidosis.[16] Mild to moderate symptoms may include tachycardia, headache, confusion, nausea, and weakness. Severe symptoms include cyanosis, coma, convulsions, cardiac arrhythmias, cardiac arrest, and death.[17]

Though the drug interactions are unknown, there is a case study where Vitamin C increases the in vitro conversion of amygdalin to cyanide and reduces the body’s cysteine storage, which is used to detoxify cyanide. [18]

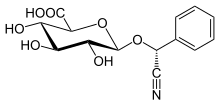

Laetrile[edit]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(2S,3S,4S,5R,6R)-6-[(R)-cyano(phenyl)methoxy]-3,4,5-trihydroxyoxane-2-carboxylic acid

| |

| Other names

L-mandelonitrile-β-D-glucuronide, Vitamin B17

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C14H15NO7 | |

| Molar mass | 309.2714 |

| Melting point | 214 to 216 °C (417 to 421 °F; 487 to 489 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Laetrile (patented 1961) is a simpler semisynthetic derivative of amygdalin. Laetrile is described to be the purified form of amygdalin.[19] Laetrile is synthesized from amygdalin by hydrolysis. The usual preferred commercial source is from apricot kernels (Prunus armeniaca). The name is derived from the separate words "laevorotatory" and "mandelonitrile". Laevorotatory describes the stereochemistry of the molecule, while mandelonitrile refers to the portion of the molecule from which cyanide is released by decomposition.[20] A 500 mg laetrile tablet may contain between 2.5 and 25 mg of hydrogen cyanide.[21]

Like amygdalin, laetrile is hydrolyzed in the duodenum (alkaline) and in the intestine (enzymatically) to D-glucuronic acid and L-mandelonitrile; the latter hydrolyzes to benzaldehyde and hydrogen cyanide, that in sufficient quantities causes cyanide poisoning.[22]

Claims for laetrile were based on four different hypotheses:[23] The first hypothesis proposed that cancerous cells contained copious beta-glucosidases and incorporates the trophoblastic theory of cancer (developed by John Beard), which release HCN from laetrile via hydrolysis. Normal cells were reportedly unaffected, because they contained low concentrations of beta-glucosidases and high concentrations of rhodanese, which converts HCN to the less toxic thiocyanate. Later, however, it was shown that both cancerous and normal cells contain only trace amounts of beta-glucosidases and similar amounts of rhodanese.[23][24]

The second proposed that, after ingestion, amygdalin was hydrolyzed to mandelonitrile, transported intact to the liver and converted to a beta-glucuronide complex, which was then carried to the cancerous cells, hydrolyzed by beta-glucuronidases to release mandelonitrile and then HCN. Mandelonitrile, however, dissociates to benzaldehyde and hydrogen cyanide, and cannot be stabilized by glycosylation.[25]: 9

The third asserted that laetrile is the discovered vitamin B-17, and further suggests that cancer is a result of "B-17 deficiency". The third hypothesis states that the cancer is a result of a metabolic disorder caused by vitamin deficiency. It states that the body is missing amygdalin/vitamin B-12 to restore homeostasis. It postulated that regular dietary administration of this form of laetrile would, therefore, actually prevent all incidences of cancer. There is no evidence supporting this conjecture in the form of a physiologic process, nutritional requirement, or identification of any deficiency syndrome.[26] There is experimental evidence that indicates that the level of vitamin intake can influence the development of cancer. However, the term "vitamin B-17" is not recognized by Committee on Nomenclature of the American Institute of Nutrition Vitamins and no evidence that laetrile is needed for normal metabolism.[20] Ernst T. Krebs (not to be confused with Hans Adolf Krebs, the discoverer of the citric acid cycle) branded laetrile as a vitamin in order to have it classified as a nutritional supplement rather than as a pharmaceutical.[2]

The fourth hypothesis suggests that cyanide release by cyanide released by laetrile has a toxic effect beyond its interference with oxygen. Cyanide would increase the acid content of the tumors leading to the destruction of lysosomes. These lysosomes will kill the cancer cells and arrest the tumor growth.

Chemistry[edit]

Laetrile is a man-made form of amygdalin. Originally, Laetrile was reported to be obtained from amygdalin by a multistep chemical synthesis. Amygdalin is commercially derived from natural sources like apricot pits. One way to synthesize laetrile is through the Koenigs-Knorr reaction. The Koenigs-Knorr reaction is the substitution reaction of glycosyl halide with an alcohol to give a glycoside and UDP glucuronosyltransferase.[27] Laetrile metabolism reflects Amygdalin’s metabolism as outlined in previous sections. Amygdalin is metabolized in the small intestine and colon using Beta-glucosidase.

Physical Properties and Uses[edit]

Laetrile, vitamin B-17, and amygdalin are used interchangeably, but they are not the same product. The US patent is a semisynthetic derivative of amygdalin, which is different from the natural product produced in Mexico, which is from crushed apricot pits.

Laetrile can be administered orally as a pill or given by intravenous or intramuscular injection. It is commonly given intravenously followed with oral maintenance therapy. Cyanide poisoning is higher when laetrile is taken orally due to intestinal bacteria and commonly eaten plants that contain beta-glucosidases, which activates the release of cyanide after ingestion.[28]

Some of its qualities include anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects. Hydrogen Cyanide is the dangerous portion while amygdalin is harmless. Amygdalin’s benefits have been studied across a wide range of medical conditions such as leprosy, colorectal cancer, asthma, bronchitis, and others.

The antidote varies depending on the type of exposure. However, the most common antidotes are hydroxocobalamin for cyanide antidote kit (containing amyl nitrite, sodium nitrate, and sodium thiosulfate. Hydroxocobalamin can be used as monotherapy. Additionally, there is research where it shows potential synergistic effects when mixed with sodium thiosulfate. A case report stated that the combined use of hydroxocobalamin and sodium thiosulfate had a positive effect on survival without the use of long term neurological and visual sequelae.[29]

History of laetrile[edit]

Early usage[edit]

Amygdalin was first isolated in 1830 from bitter almond seeds (Prunus dulcis) by Pierre-Jean Robiquet and Antoine Boutron-Charlard.[30] Liebig and Wöhler found three hydrolysis products of amygdalin: sugar, benzaldehyde, and prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide, HCN).[31] Later research showed that sulfuric acid hydrolyzes it into D-glucose, benzaldehyde, and prussic acid; while hydrochloric acid gives mandelic acid, D-glucose, and ammonia.[32]

In 1845 amygdalin was used as a cancer treatment in Russia due to high its toxicity and poor efficacy. Scientists believe that the hydrogen cyanide was the main anticancer compound. Many countries started to speculate the efficiency, and Germany and the United States rejected Laetrile as a cancer treatment in 1892 and 1920s respectively due to it being dangerous. Laetrile showed little anticancer activity in animal studies and no anticancer activity in human trials. In 1940, Ernst T. Krebs reintroduced the trophoblast theory, proposing that all cancer forms originate from undifferentiated cells known as trophoblasts. This theory aimed to propose the mechanism behind Laetrile's ‘effectiveness’ against cancer cells. In the 1950s, a purportedly non-toxic, synthetic intravenous form was patented for use as a meat preservative, and later marketed as laetrile for cancer treatment, but quickly rejected by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[17]

In 1970, an IND application to study laetrile was filed by the McNaughton Foundation. It was initially approved but rejected later due to the lack of evidence as an anticancer agent and questions on the study’s procedures. However, Laetrile supporters viewed this reversal as an attempt by the United States Government to block access to new and promising cancer therapies. There were court cases in Oklahoma, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and California that challenged the FDA’s role in determining which drugs should be available to cancer patients. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration prohibited the interstate shipment of amygdalin and laetrile in 1977. Thereafter, 27 U.S. states legalized the use of amygdalin within those states. In 1980, the United States Supreme Court acted to uphold a federal ban on interstate shipment of laetrile, and the use of laetrile greatly diminished.

In Traditional Chinese Medicine, Amygdalin is a therapeutic medicine used to “remove blood stasis' ' and treat abcesses. Blood stasis is a concept that has stagnant blood within the body which loses its physiological functions. It is often referred as “Xing Ren '' and sourced from apricot kernels. It is believed that amygdalin can selectively target cancer cells and kill them while sparing healthy cells.[33][34]

In parts of North Africa, Middle East, and sub-Saharan African countries, apricot seeds containing amygdalin are used in traditional remedies as a powder for teas, poultices, and other preparations. In addition, traditional healers in Africa may use plants and other ingredients as its components are believed to have medicinal effects.[35]

Subsequent results[edit]

In a 1977 controlled, blinded trial, laetrile showed no more activity than placebo.[27]

Subsequently, laetrile was tested on 14 tumor systems without evidence of effectiveness. The Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) concluded that "laetrile showed no beneficial effects."[27] Mistakes in an earlier MSKCC press release were highlighted by a group of laetrile proponents led by Ralph Moss, former public affairs official of MSKCC who had been fired following his appearance at a press conference accusing the hospital of covering up the benefits of laetrile.[36] These mistakes were considered scientifically inconsequential, but Nicholas Wade in Science stated that "even the appearance of a departure from strict objectivity is unfortunate."[27] The results from these studies were published all together.[37]

A 2015 systematic review from the Cochrane Collaboration found:

The claims that laetrile or amygdalin have beneficial effects for cancer patients are not currently supported by sound clinical data. There is a considerable risk of serious adverse effects from cyanide poisoning after laetrile or amygdalin, especially after oral ingestion. The risk–benefit balance of laetrile or amygdalin as a treatment for cancer is therefore unambiguously negative.[3]

The authors also recommended, on ethical and scientific grounds, that no further clinical research into laetrile or amygdalin be conducted.[3]

Given the lack of evidence, laetrile has not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or the European Commission.

The U.S. National Institutes of Health evaluated the evidence separately and concluded that clinical trials of amygdalin showed little or no effect against cancer.[38] For example, a 1982 trial by the Mayo Clinic of 175 patients found that tumor size had increased in all but one patient.[39] The authors reported that "the hazards of amygdalin therapy were evidenced in several patients by symptoms of cyanide toxicity or by blood cyanide levels approaching the lethal range."

The study concluded "Patients exposed to this agent should be instructed about the danger of cyanide poisoning, and their blood cyanide levels should be carefully monitored. Amygdalin (Laetrile) is a toxic drug that is not effective as a cancer treatment".

Additionally, "No controlled clinical trials (trials that compare groups of patients who receive the new treatment to groups who do not) of laetrile have been reported."[38]

The side effects of laetrile treatment mirrors the symptoms of cyanide poisoning. These symptoms include: nausea and vomiting, headache, dizziness, cherry red skin color, liver damage, abnormally low blood pressure, droopy upper eyelid, trouble walking due to damaged nerves, fever, mental confusion, coma, and death. Oral laetrile causes more severe side effects than injected laetrile because our digestive system breaks down the laetriles and releases cyanide.[40]

The European Food Safety Agency's Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain has studied the potential toxicity of the amygdalin in apricot kernels. The Panel reported, "If consumers follow the recommendations of websites that promote consumption of apricot kernels, their exposure to cyanide will greatly exceed" the dose expected to be toxic. The Panel also reported that acute cyanide toxicity had occurred in adults who had consumed 20 or more kernels and that in children "five or more kernels appear to be toxic".[25]

Advocacy and Legality of Laetrile[edit]

Advocates for laetrile assert that there is a conspiracy between the US Food and Drug Administration, the pharmaceutical industry and the medical community, including the American Medical Association and the American Cancer Society, to exploit the American people, and especially cancer patients.[41]

Advocates of the use of laetrile have also changed the rationale for its use, first as a treatment of cancer, then as a vitamin, then as part of a "holistic" nutritional regimen, or as treatment for cancer pain, among others, none of which have any significant evidence supporting its use.[41]

Despite the lack of evidence for its use, laetrile developed a significant following due to its wide promotion as a "pain-free" treatment of cancer as an alternative to surgery and chemotherapy that have significant side effects. The use of laetrile led to a number of deaths.[41] The FDA and AMA crackdown, begun in the 1970s, effectively escalated prices on the black market, played into the conspiracy narrative and enabled unscrupulous profiteers to foster multimillion-dollar smuggling empires.[42]

Some American cancer patients have traveled to Mexico for treatment with the substance, for example at the Oasis of Hope Hospital in Tijuana.[43] The actor Steve McQueen died in Mexico following surgery to remove a stomach tumor, having previously undergone extended treatment for pleural mesothelioma (a cancer associated with asbestos exposure) under the care of William D. Kelley, a de-licensed dentist and orthodontist who claimed to have devised a cancer treatment involving pancreatic enzymes, 50 daily vitamins and minerals, frequent body shampoos, enemas, and a specific diet as well as laetrile.[44]

Laetrile advocates in the United States include Dean Burk, a former chief chemist of the National Cancer Institute cytochemistry laboratory,[45] and national arm wrestling champion Jason Vale, who falsely claimed that his kidney and pancreatic cancers were cured by eating apricot seeds. Vale was convicted in 2004 for, among other things, fraudulently marketing laetrile as a cancer cure.[46] The court also found that Vale had made at least $500,000 from his fraudulent sales of laetrile.[47]

In the 1970s, court cases in several states challenged the FDA's authority to restrict access to what they claimed are potentially lifesaving drugs. More than twenty states passed laws making the use of laetrile legal. After the unanimous Supreme Court ruling in United States v. Rutherford[48] which established that interstate transport of the compound was illegal, usage fell off dramatically.[20][49]

The Supreme Court Case for the United States v. Rutherford was a pivotal case marking the interstate transport of laetrile illegal. Rutherford became ill with cancer in the summer and fall of 1971 and was diagnosed with cancer after going to Dr. J Walker Butin MD of Wichita Clinic. Rutherford was upset about the potential surgeries, so he went to Centro Medico Del Mar in Tijuana Mexico for another exam and to pursue treatment. The doctors at the clinic treated Rutherford with Vitamin B17 for a period of weeks. When Rutherford was getting better and had no ill effect of the cancer, he planned on coming back to the United States. However, without the continued use of laetrile as diagnosed by Dr. Carlos Lopez, he was afraid of escalation of cancer cells. The Court found Rutherford to not be free to have shipped or purchased the Vitamin B12 pills back to the United States, and found the FDA abdicated its duty to make clear determination of which drugs should or should not be placed in commerce.[50]

The US Food and Drug Administration continues to seek jail sentences for vendors marketing laetrile for cancer treatment, calling it a "highly toxic product that has not shown any effect on treating cancer."[51]

Controversy[edit]

There are several reasons why researchers and physicians reject laetrile. First, most laetrile advocates reject the theories of contemporary oncology and postulate a trophoblastic theory on cancer. The trophoblastic theory of cancer suggests that cancer cells behave similarly to trophoblastic cells in early pregnancy, leading to the development of an alternative treatment like laetrile. The second issue is the debate on the early detection of cancer. Early proponents believed that cancer and pregnancy shared similarities, including certain biomarkers detectable through a urine test, such as the Beta hCG Pregnancy Tests (BAT). However, medical leaders – like the California Department of Public Health – have discredited BAT, citing its lack of sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing cancer. Additionally, claims regarding the ingestion of inadequate amounts of vitamin B17 found in laetrile have sparked epidemiological arguments. Despite being dubbed a vitamin by some, there’s scant evidence supporting this classification. Fourth, Laetrile’s proposed mechanism in cancer therapy involves targeting cancer cells with high levels of beta-glucosidases, but concerns arise over its efficacy due to studies suggesting lower levels in cancer cells than initially thought. Moreover, there the debate over whether laetrile can cure or control cancer persist due to insufficient data and research. While advocates argue for its “non-toxic” nature, scientific findings reveal its highly toxic properties. Sloan Kettering Cancer Center reports concluded amygdalin ineffective, adding to the ongoing controversy and research around its use in cancer treatment.[52]

In popular culture[edit]

The Law & Order episode "Second Opinion" is about a nutritional counselor named "Doctor" Haas giving patients laetrile as a cancer treatment for breast cancer as an alternative to getting a mastectomy.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Apricot kernels pose risk of cyanide poisoning". European Food Safety Authority. 27 April 2016.

A naturally-occurring compound called amygdalin is present in apricot kernels and converts to hydrogen cyanide after eating. Cyanide poisoning can cause nausea, fever, headaches, insomnia, thirst, lethargy, nervousness, joint and muscle various aches and pains, and falling blood pressure. In extreme cases it is fatal

- ^ a b c Lerner IJ (1981). "Laetrile: a lesson in cancer quackery". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 31 (2): 91–5. doi:10.3322/canjclin.31.2.91. PMID 6781723. S2CID 28917628.

- ^ a b c Milazzo S, Horneber M (April 2015). "Laetrile treatment for cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (4): CD005476. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005476.pub4. PMC 6513327. PMID 25918920.

- ^ Lerner IJ (February 1984). "The whys of cancer quackery". Cancer. 53 (3 Suppl): 815–9. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3+<815::AID-CNCR2820531334>3.0.CO;2-U. PMID 6362828. S2CID 36332694.

- ^ Nightingale SL (1984). "Laetrile: the regulatory challenge of an unproven remedy". Public Health Reports. 99 (4): 333–8. PMC 1424606. PMID 6431478.

- ^ "Amygdalin - Molecule of the Month - November 2017 (JSMol version)". www.chm.bris.ac.uk. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ Mora CA, Halter JG, Adler C, Hund A, Anders H, Yu K, Stark WJ (May 2016). "Application of the Prunus spp. Cyanide Seed Defense System onto Wheat: Reduced Insect Feeding and Field Growth Tests". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 64 (18): 3501–7. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.6b00438. PMID 27119432.

- ^ Bolarinwa, Islamiyat F.; Orfila, Caroline; Morgan, Michael R.A. (2014). "Amygdalin content of seeds, kernels and food products commercially-available in the UK" (PDF). Food Chemistry. 152: 133–139. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.002. PMID 24444917. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Sanchez-Perez, R.; Jorgensen, K.; Olsen, C. E.; Dicenta, F.; Moller, B. L. (2008). "Bitterness in Almonds". Plant Physiology. 146 (3): 1040–1052. doi:10.1104/pp.107.112979. PMC 2259050. PMID 18192442.

- ^ Lee, Jihyun; Zhang, Gong; Wood, Elizabeth; Rogel Castillo, Cristian; Mitchell, Alyson E. (2013). "Quantification of Amygdalin in Nonbitter, Semibitter, and Bitter Almonds (Prunus dulcis) by UHPLC-(ESI)QqQ MS/MS". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 61 (32): 7754–7759. doi:10.1021/jf402295u. PMID 23862656. S2CID 22497338.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 900.

- ^ Wahab MF, Breitbach ZS, Armstrong DW, Strattan R, Berthod A (October 2015). "Problems and Pitfalls in the Analysis of Amygdalin and Its Epimer". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 63 (40): 8966–73. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b03120. PMID 26431391.

- ^ "Method for removing chromium containing coatings from aluminum". Metal Finishing. 93 (6): 147. 1995-06. doi:10.1016/0026-0576(95)94717-5. ISSN 0026-0576.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ George Mann F, Charles Saunders B (1975). Practical Organic Chemistry (4th ed.). London: Longman. pp. 509–517. ISBN 9788125013808. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ "Medical Management Guidelines (MMGs): Hydrogen Cyanide (HCN)". ATSDR. 21 October 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Graham, Jeremy; Traylor, Jeremy (2024), "Cyanide Toxicity", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29939573, retrieved 6 May 2024

- ^ a b "Laetrile/Amygdalin (PDQ®) - NCI". www.cancer.gov. 10/15/2023 - 08:00. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Bromley, Jonathan; Hughes, Brett G. M.; Leong, David C. S.; Buckley, Nicholas A. (2005-09). "Life-threatening interaction between complementary medicines: cyanide toxicity following ingestion of amygdalin and vitamin C". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 39 (9): 1566–1569. doi:10.1345/aph.1E634. ISSN 1060-0280. PMID 16014371.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Laetrile (amygdalin or vitamin B17)". www.cancerresearchuk.org. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Pdq Integrative, Alternative (15 March 2017). "Laetrile/Amygdalin (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version: General Information". cancer.gov. Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Health Professionals. National Cancer Institute. PMID 26389425. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ Jerrold B. Leikin; Frank P. Paloucek, eds. (2008), "Laetrile", Poisoning and Toxicology Handbook (4th ed.), Informa, p. 950, ISBN 978-1-4200-4479-9

- ^ Rietjens IM, Martena MJ, Boersma MG, Spiegelenberg W, Alink GM (February 2005). "Molecular mechanisms of toxicity of important food-borne phytotoxins". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 49 (2): 131–58. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200400078. PMID 15635687.

- ^ a b Duke JA (2003). CRC Handbook of Medicinal Spices. CRC Press. pp. 261–262. ISBN 978-0-8493-1279-3.

- ^ "Laetrile/Amygdalin (PDQ®) - NCI". www.cancer.gov. 10/15/2023 - 08:00. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Acute health risks related to the presence of cyanogenic glycosides in raw apricot kernels and products derived from raw apricot kernels". EFSA Journal. 14 (4). 2016. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4424. hdl:2164/7789.

- ^ Greenberg DM (April 1975). "The vitamin fraud in cancer quackery". The Western Journal of Medicine. 122 (4): 345–8. PMC 1129741. PMID 1154776.

- ^ a b c d Wade N (December 1977). "Laetrile at Sloan-Kettering: a question of ambiguity". Science. 198 (4323): 1231–4. Bibcode:1977Sci...198.1231W. doi:10.1126/science.198.4323.1231. PMID 17741690.

- ^ PDQ Integrative, Alternative, and Complementary Therapies Editorial Board (2002), "Laetrile/Amygdalin (PDQ®): Health Professional Version", PDQ Cancer Information Summaries, Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US), PMID 26389425, retrieved 6 May 2024

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dang, Tam; Nguyen, Cham; Tran, Phu N. (2017). "Physician Beware: Severe Cyanide Toxicity from Amygdalin Tablets Ingestion". Case Reports in Emergency Medicine. 2017: 1–3. doi:10.1155/2017/4289527. ISSN 2090-648X. PMC 5587935. PMID 28912981.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "A chronology of significant historical developments in the biological sciences". Botany Online Internet Hypertextbook. University of Hamburg, Department of Biology. 18 August 2002. Archived from the original on 20 August 2007. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ^ Wöhler, F.; Liebig, J. (1837). "Ueber die Bildung des Bittermandelöls". Annalen der Pharmacie. 22 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1002/jlac.18370220102. S2CID 96869201.

- ^ Walker, J. W.; Krieble, V. K. (1909). "The hydrolysis of amygdalin by acids. Part I". Journal of the Chemical Society. 95 (11): 1369–77. doi:10.1039/CT9099501369.

- ^ Li, Yun-Long; Li, Qiao-Xing; Liu, Rui-Jiang; Shen, Xiang-Qian (2018-03). "Chinese Medicine Amygdalin and β-Glucosidase Combined with Antibody Enzymatic Prodrug System As A Feasible Antitumor Therapy". Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 24 (3): 237–240. doi:10.1007/s11655-015-2154-x. ISSN 1993-0402. PMID 26272547.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Jiang, Huajuan; Li, Minmin; Du, Kequn; Ma, Chuan; Cheng, Yanfen; Wang, Shengju; Nie, Xin; Fu, Chaomei; He, Yao (2021-12). "Traditional Chinese Medicine for adjuvant treatment of breast cancer: Taohong Siwu Decoction". Chinese Medicine. 16 (1). doi:10.1186/s13020-021-00539-7. ISSN 1749-8546. PMC 8638166. PMID 34857023.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Spanoudaki, Maria; Stoumpou, Sofia; Papadopoulou, Sousana K.; Karafyllaki, Dimitra; Solovos, Evangelos; Papadopoulos, Konstantinos; Giannakoula, Anastasia; Giaginis, Constantinos (19 September 2023). "Amygdalin as a Promising Anticancer Agent: Molecular Mechanisms and Future Perspectives for the Development of New Nanoformulations for Its Delivery". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 24 (18): 14270. doi:10.3390/ijms241814270. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 10531689. PMID 37762572.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Budiansky S (9 July 1995). "Cures or Quackery: How Senator Harkin shaped federal research on alternative medicine". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- ^ Stock CC, Tarnowski GS, Schmid FA, Hutchison DJ, Teller MN (1978). "Antitumor tests of amygdalin in transplantable animal tumor systems". Journal of Surgical Oncology. 10 (2): 81–8. doi:10.1002/jso.2930100202. PMID 642516. S2CID 5896930. Stock CC, Martin DS, Sugiura K, Fugmann RA, Mountain IM, Stockert E, Schmid FA, Tarnowski GS (1978). "Antitumor tests of amygdalin in spontaneous animal tumor systems". Journal of Surgical Oncology. 10 (2): 89–123. doi:10.1002/jso.2930100203. PMID 347176. S2CID 22185766.

- ^ a b "Laetrile/Amygdalin". National Cancer Institute. 23 September 2005.

- ^ "Laetrile (amygdalin, vitamin B17)". cancerhelp.org.uk. 30 August 2017.

- ^ "Laetrile/Amygdalin - NCI". www.cancer.gov. 09/23/2005 - 08:00. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c Editors of Consumer Reports Books (1980). "Laetrile: the Political Success of a Scientific Failure". Health Quackery. Vernon, New York: Consumers Union. pp. 16–40. ISBN 978-0-89043-014-9.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Herbert, V (1979). "Laetrile: the cult of cyanide Promoting poison for profit". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 32 (5): 1121–1158. doi:10.1093/ajcn/32.5.1121. PMID 219680.

- ^ Moss RW (March 2005). "Patient perspectives: Tijuana cancer clinics in the post-NAFTA era". Integrative Cancer Therapies. 4 (1): 65–86. doi:10.1177/1534735404273918. PMID 15695477.

- ^ Lerner BH (15 November 2005). "McQueen's Legacy of Laetrile". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Dean Burk, 84, Noted Chemist At National Cancer Institute, Dies". The Washington Post. 9 October 1988. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- ^ McWilliams BS (2005). Spam kings: the real story behind the high-rolling hucksters pushing porn, pills and @*#?% enlargements. Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-596-00732-4.

Jason Vale.

- ^ "New York Man Sentenced to 63 Months for Selling Fake Cancer Cure". Medical News Today. 22 June 2004. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ United States v. Rutherford, 442 U.S. 544 (United States Supreme Court 1979).

- ^ Curran WJ (March 1980). "Law-medicine notes. Laetrile for the terminally ill: Supreme Court stops the nonsense". The New England Journal of Medicine. 302 (11): 619–21. doi:10.1056/NEJM198003133021108. PMID 7351911.

- ^ Hoogenboom, Ari (2000-02). Hayes, Rutherford Birchard (1822-1893), nineteenth president of the United States. American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Lengthy Jail Sentence for Vendor of Laetrile – A Quack Medication to Treat Cancer Patients". FDA. 22 June 2004. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009.

- ^ Petersen, James C.; Markle, Gerald E. (1979). "Politics and Science in the Laetrile Controversy". Social Studies of Science. 9 (2): 139–166. ISSN 0306-3127.