User:Serkatet/Lost-wax casting

Greece, Rome, and the Mediterranean[edit]

The lost-wax technique came to be known in the Mediterranean during the Bronze Age.[1] It was a major metalworking technique utilized in the ancient Mediterranean world, notably during the Classical period of Greece for large-scale bronze statuary[2] and in the Roman world.

Direct imitations and local derivations of Oriental, Syro-Palestinian and Cypriot figurines are found in Late Bronze Age Sardinia, with a local production of figurines from the 11th to 10th century BC.[1]The cremation graves (mainly 8th-7th centuries BC, but continuing until the beginning of the 4th century) from the necropolis of Paularo (Italian Oriental Alps) contained fibulae, pendants and other copper-based objects that were made by the lost-wax process.[3] Etruscan examples, such as the bronze anthropomorphic handle from the Bocchi collection (National Archaeological Museum of Adria), dating back to the 6th to 5th centuries BC, were made by cire perdue.[4] Most of the handles in the Bocchi collection, as well as some bronze vessels found in Adria (Rovigo, Italy) were made using the lost-wax technique.[4] The better known lost-wax produced items from the classical world include the "Praying Boy" c. 300 BC (in the Berlin Museum), the statue of Hera from Vulci (Etruria), which, like most statues, was cast in several parts which were then joined together.[5] Geometric bronzes such as the four copper horses of San Marco (Venice, probably 2nd century) are other prime examples of statues cast in many parts.[6]

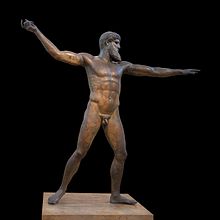

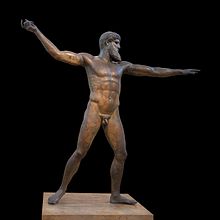

Examples of works made using the lost-wax casting process in ancient Greece largely are unavailable due to the common practice in later periods of melting down pieces to reuse their materials.[8] Much of the evidence for these products come from shipwrecks.[9] As underwater archaeology became more feasible, artifacts lost to the sea became more accessible.[9] Statues like the Artemision Bronze Zeus or Poseidon (found near Cape Artemision), as well as the Victorious Youth (found near Fano), are two such examples of Greek lost-wax bronze statuary that were discovered underwater.[9][10]

Some Late Bronze Age sites in Cyprus have produced cast bronze figures of humans and animals. One example is the male figure found at Enkomi.[11] Three objects from Cyprus (held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York) were cast by the lost-wax technique from the 13th and 12th centuries BC, namely, the amphorae rim, the rod tripod, and the cast tripod.[11]

Other, earlier examples that show this assembly of lost-wax cast pieces include the bronze head of the Chatsworth Apollo and the bronze head of Aphrodite from Satala (Turkey) from the British Museum.[12]

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Notes on the Draft[edit]

Plans for Contributions[edit]

The section that is labelled "Greek, Roman and Mediterranean", lacks a bunch of potential examples of later Greek bronze sculptures

Additionally, could use more background information on why there isn't many surviving ancient Greek bronzes

Possibly add image of Artemision Zeus/Poseidon bronze sculpture

still looking for sources on this item specifically

Might try to condense section, or potentially divide it? It seems a lot longer in relation to the other sections

definitely discuss shipwrecks

add more information to captions on images maybe

Potential Sources[edit]

Fullerton, Mark D.. Greek Sculpture. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2016. Accessed November 15, 2021. ProQuest Ebook Central.

contains information on construction of sculpture and also why there isn't many examples of ancient Greek bronze sculpture left today (they were melted down and the bronze was reused)

Dillon, Sheila. American Journal of Archaeology 101, no. 4 (1997): 806–7. https://doi.org/10.2307/506861.

references the usage of lost wax casting method in ancient greece

Sparkes, Brian A. “Greek Bronzes.” Greece & Rome 34, no. 2 (1987): 152–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/642943.

this source briefly discusses underwater archaeology, and sculptures found by this means

Konstantinidi-Syvridi, E., & Kontaki, M. (2009). CASTING FINGER RINGS IN MYCENAEAN TIMES: TWO UNPUBLISHED MOULDS AT THE NATIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL MUSEUM, ATHENS. The Annual of the British School at Athens, 104, 311–319. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20745370

References[edit]

- ^ a b LoSchiavo, F. "Early Metallurgy in Sardinia" (Document).

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help) In Maddin 1988 - ^ Fullerton, Mark D. (2016). Greek Sculpture. The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. p. 139. ISBN 9781119115311.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Giumlia-Mair, A.; Vitre, S.; Corazza, S. "Iron Age Copper-Based Finds from the Necropolis of Paularo in the Italian Oriental Alps" (Document).

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help) In Archaeometallurgy in Europe 2003 - ^ a b Bonomi, S.; Martini, G.; Poli, G.; Prandstraller, D. (September 2003). Modernity of Early Metallurgy: Studies on an Etruscan Anthropomorphic Bronze Handle. Archaeometallurgy in Europe. Milan: Associazione Italiana di Metallurgia.

- ^ Neuburger, A., 1930. The Technical Arts and Sciences of the Ancients, London: Methuen & Co. Ltd.

- ^ Darling, A. S., (1990). Non-Ferrous Materials, in An Encyclopaedia of the History of Technology, ed. I. McNeil London and New York: Routledge.

- ^ Mattusch, Carol C. (1997). The Victorious Youth. Los Angeles, California: Christopher Hudson. p. 10. ISBN ISBN 0-89236-470-x.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Fullerton, Mark D. (2016). Greek Sculpture. The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. pp. 139–40. ISBN 9781119115311.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b c Sparkes, Brian A. (1987). "Greek Bronzes". Greece & Rome. 34 (2): 152–168. doi:10.1017/S0017383500028102. JSTOR 642943. S2CID 248520562 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Lloyd, James (2012). "The Artemision Bronze". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Schorsch, D.; Hendrix, E. "The Production of Relief Ornament on Cypriot Bronze Castings of The Late Bronze Age" (Document).

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help) In Archaeometallurgy in Europe 2003 - ^ Maryon, Herbert (1956). "Fine Metal-Work". In Singer, E. J. H. Charles; Hall, A. R.; Williams, Trevor I. (eds.). The Mediterranean Civilizations and The Middle Ages c. 700 BC. to c. AD. 1500. A History of Technology. Vol. II. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-019858106-2. OCLC 491563676.; See also Dafas, K. A., 2019. Greek Large-Scale Bronze Statuary: The Late Archaic and Classical Periods, Institute of Classical Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, Monograph, BICS Supplement 138 (London).