User:Penguin2006/Fair Head

|

This is the user sandbox of Penguin2006. A user sandbox is a subpage of the user's user page. It serves as a testing spot and page development space for the user and is not an encyclopedia article. For a sandbox of your own, create it here.

Other sandboxes: Main sandbox | Tutorial sandbox 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | Template sandbox If you are writing an article, and are ready to request its creation, click here. |

| Fair Head | |

|---|---|

| an Bhinn Mhór | |

Fair Head seen from Ballycastle | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 196 m (643 ft) |

| Coordinates | 55°13′16″N 6°09′14″W / 55.221°N 6.154°W |

| Naming | |

| Language of name | lang-ga |

| Geography | |

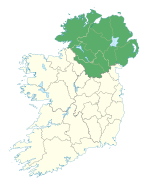

| Location | County Antrim, Northern Ireland |

| OSI/OSNI grid | D180438 |

| Topo map | OSNI Discoverer 5 |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Paleogene dolerite sill |

Fair Head (Irish: an Bhinn Mhór) is the most prominent headland of the north Antrim coast.[1] It is three miles (five km) east of the town of Ballycastle and the closest part of the mainland to Rathlin Island.

The largest settlement is the small clachan of Craigfad with less than a dozen houses. The eastern side of the headland is designated a coastal reserve.[2] But Fair Head has been inhabited since prehistoric times. In the eighteenth century it was the site of large scale industries, including coal mines. In the nineteenth century, it became a tourist destination.[3]

Among rock climbers, Fair Head has the reputation as being the 'best crag in the UK'.[4]

Public access[edit]

The east side of Fair Head is owned by the National Trust. It has one car park on top of the headland, at Lough na Cranagh, and another at nearby Murlough Bay.[3]

Access to the rest of the headland is at the discretion of local landowners. Even well-established trails like the Grey Man's Path cut through private land.[3]

The one public car park can be found to the west in Collier's Bay beside Marconi's Cottage.[3]

The Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure stocks the lakes at Lough na Cranagh and Lough Doo with fingerling brown trout. A permit is necessary to fish here.[5]

Geology[edit]

Fair Head is the largest and thickest sill in north east Ireland, 85 m at its widest.[1]

50 to 60 million years ago, about the same time that the Giant's Causeway was formed, molten rock was injected roughly horizontally through existing sedimentary layers. The sill tilts down slightly inland, to the south, and so cuts through the sedimentary rock's layers - first the distinctive Cretaceous Ulster chalk, then Triassic sandstones and then Carboniferous shales containing coal which are the last visible layer at Fair Head,[6] although much older Dalradian schists are visible underneath this at Murlough Bay.[7]

The olivine dolerite that makes up Fair Head sill is similar in composition to the basalt that forms the columns of the Giant's Causeway, except that the dolerite solidified underground, more slowly, and so is a coarser grained, harder rock with much more massive columnar jointing. Some of the crude columns at Fair Head extend up to 15 m wide.[3]

This durable dolerite has eroded less than the surrounding rocks, creating the distinctive headland of Fair Head.[1]

History[edit]

Ptolemy's Geography[edit]

In the second century, Ptolemy of Alexandria referred to Fair Head in his Geographia, probably calling it the Rhobogdion promontory,[8] and included it on his map of the world[1] naming the local peoples the Rhobogdioi.[8]

Crannog and other prehistoric remains[edit]

An artificial island or crannog is in a small lake on the top of the headland. The age of the crannog is uncertain, but has been dated between early Christian to Iron Age. The crannog is oval and unusual in being completely surrounded by drystone walls, still three to four feet high.[9][10]

The island itself was built using boulders topped with laterite - a distinctive weathered basalt found in layers on the surrounding coast between the more common dark rock.[9] Laterite may have had significance to early inhabitants as an important source of iron ore and due to its bright red colour.[11]

A passage tomb, a possible wedge tomb and a court tomb, a rath and various cairns also attest to an early presence here.[10][3]

Norman fort (ruins)[edit]

The remains of a mound or fortified outcrop is at Doonmore Fort.[12] The Anglo-Normans arrived in Northern Ireland in 1177, with the baron John de Courcy dubbed the 'Conqueror of Ulster'. After de Courcy grew too powerful, King John seized his lands after a battle. Even more fortifications were built along in this area in the thirteenth century as John arrived in Ireland and fought other rebel barons, especially at Carrickfergus.[13]

Coal mining[edit]

In the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a complex of industries based on coal mining developed around the coastline of Fair Head.[11] Since before 1629, salt had been mined at the coalfields between Ballycastle and Murlough Bay. From 1735, Hugh Boyd took control of them and greatly expanded their output, building a new harbour at Ballycastle and shipping coal as far as Belfast and Dublin, fuelling the Irish Industrial Revolution.By 1759, Boyd claimed that the supply of Ballycastle coal had saved the nation £829,000.[14]

A glassworks, built by Boyd, also depended on a regular supply of local coal. [14]Other activities that sprung up were lime kilns, soap manufacture and iron smelting.[11]

Boyd died in 1765, after which much of the industry faded away. Mining continued on a smaller scale until the 1960s. Today, the coal seam is mostly worked out, leaving just the name of Colliery Bay.[11]

The closed coal mines should not be entered as they are highly dangerous due to instability.[7]

Marconi's Cottage[edit]

In 1898, Guglielmo Marconi and his assistant, George Stephen Kemp, arranged wireless transmissions on behalf of Lloyds between White Lodge, a house on top of the cliff at Ballycastle, and a mast erected near Rathlin Island's east lighthouse.[15] On Fair Head, a house is locally known as Marconi's Cottage and has been marketed on this basis by estate agents. There is no definite evidence that Marconi ever stayed here.[16][3]

In art[edit]

Fair Head has been popular with artists since Victorian times.

- In 1842, Robert Brandard made a steel engraving after a study from the William Henry Bartlett part-work The Scenery and Antiquities of Ireland[17]

- Thomas Creswick made a painting of Fair Head, after which which steel engravings were made

- Maurice Canning Wilks painted several studies in watercolour and oils

- In 1932, Paul Henry produced a poster promoting Ulster as a tourist destination

- Other artists include James Humbert Craig

Climbing[edit]

Fair Head is widely regarded as Ireland's finest rock-climbing crag, and is believed to be the biggest expanse of climbable rock in either Ireland or Britain, but for a variety of reasons including its relatively remote location and the physical strength and unfamiliar climbing techniques often required there, does not attract the volume of climbers that one might expect at a crag of such quality.

Its cliffs stretch for a distance of over 5 km around the headland, rising to a maximum height of over 100m. They are not sea-cliffs, but have been described as a mountain crag by the sea, since they tower above an extensive boulder field and their isolation and size gives climbing there a big-wall mountaineering feel.

The cliffs are composed of dolerite, giving a mixture of steep cracked walls, corners, and, in many places, sets of columns reminiscent of organ-pipes. The dolerite sits on top of a bed of chalk which is visible in places.

The cliffs abound in well-protected steep crack climbing, between one and four pitches long. Many of the cracks involve hand-jamming, so some climbers tape their hands to protect the skin from what they term "Fair Head rash". Other climbs involve off-width or full-width chimneying, which is not often encountered in other Irish crags. As with nearly all Irish crags, only traditional protection ("clean climbing") is used.

The current guidebook, published in 2002, lists about 400 routes from under grade VS 4c up to E6 6b, but more recent climbing includes routes up to E8 6c.

Climbing History[edit]

The first climbs at Fair Head were done in the mid-1960s by some Belfast-based climbers and members of the Dublin-based Spillikin Club. Most of these climbs followed loose and dirty chimneys and are rarely repeated nowadays, but the seed had been planted, and before the end of the sixties development of the crag had started in earnest. However, it was not long before the increasing political violence in the North started making its presence felt; the Fair Head area was generally unaffected, but development of the crag slowed to a trickle during the early 1970s. However the attractions of Fair Head eventually proved irresistible and development picked up again in the late seventies, led by the husband-and-wife team of Calvin Torrans and Clare Sheridan and a number of other Dublin climbers. This small band devoted themselves to developing Fair Head, founded the Dal Riada Climbing Club (named after the ancient kingdom which included this area), and acquired a climbing hut nearby to accommodate themselves and other visiting climbers. There is still unclimbed rock at Fair Head; opportunities, mainly in the higher grades, are waiting for those who have the talent and dedication.

Layout[edit]

The cliffs are divided into several main sectors. From east to west, these are:

- The Small Crag. This 20m-high sector containing about seventy climbs stretches for 1 km above a heavily-forested hillside; the difficulty of access means that abseiling in is usually necessary. Together with the problems often caused by midges, this make the sector unpopular, in spite of the quality of climbing to be had there.

- The Main Crag (including The Prow at its western end) is by far the most important sector. It curves around the headland for 3 km, and contains the longest and best-quality climbs, up to 100m in height. Access is gained mainly by two easy descent gullies near either end of the sector, the Grey Man's Path at the east, and the Ballycastle Gully at the west. The Ballycastle Gully tends to be the more popular descent route for casual visitors, as there is a concentration of easier climbs in the vicinity. Between the two gullies, the starts of climbs can be reached by picking one's way through the boulder-field or by doing a usually-vertical abseil of up to 100m.

- Farrangandoo. This popular small sector consists of columns with intervening cracks every 2m or so, and contains about 30 single-pitch climbs.

- Marconi's Cove is about 500m distant from the rest of the crag, and was not discovered until 1988, but contains about 25 good-quality single-pitch climbs.

Base camps are usually established near the tops of the descent routes; the walk-ins this far are pleasant and quite short, through the open grazing fields above the crag. However, access to some of the climbs themselves can be quite rough and time-consuming.

Visiting[edit]

The Dal Riada Climbing Club formerly had the use of a series of buildings which they operated as climbing huts which they used to accommodate themselves and other visiting climbers, but this ended in 2007 when the last one was repossessed by its owners, the National Trust [1]. The most popular options now are either camping at a nearby campsite operated by a local farmer, or staying at a hostel in Ballycastle town, where there is a selection of bars and restaurants.[19]

Gallery[edit]

-

From Ireland, its Scenery and Character, published 1841-3

-

Engraving from Illustrated London News, 1874

-

Murlough Bay side of Fair Head

-

Trapezoidal cairn (possible wedge tomb) in field at Coolanlough

-

Remains of Norman motte

-

View from 'Marconi's' cottage towards Ballycastle

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Calvin Torrans and Clare Sheridan (editors), Fair Head Rock Climbing Guide (Mountaineering Ireland, 2002) ISBN 0-902940-18-X [2]

- ^ a b c d Habitas, National Museums Northern Ireland, Geological Sites Northern Ireland, Earth Science Conservation Review, Fair Head Site Description Cite error: The named reference "habitas" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ The Glens of Antrim Historical Society, Clachan Project, Craigfad

- ^ a b c d e f g BBC Northern Ireland, Off the Beaten Track, Fair Head

- ^ Paul Swail, UK Climbing, REPORT: Fair Head Meet 2012

- ^ UK Government, NI Direct Government Services, Angling at Lough Na Cranagh and Lough Doo

- ^ Habitas, National Museums Northern Ireland, Geological Sites Northern Ireland, Earth Science Conservation Review,Fair Head site Summary

- ^ a b Molloys, Tilly, Rockin' The Causeway Coast and Glens A visitor's guide to the geology of the causeway coast and glens, Causeway Coast & Glens Heritage Trust

- ^ a b Robert Faulder, C. Dilly, and J. Egerton (1794) Memoirs of science and the arts: or, An abridgement of the transactions published by the principal learned and œconomical societies established in Europe, Asia, and America, Volume 1

- ^ a b The Modern Antiquarian, Lough-na-Cranagh, Crannog

- ^ a b Irish Megaliths, Gazeteer of Irish Prehistoric Monuments, Selected Monuments in Country Antrim, Lough-na-Cranagh, Crannog

- ^ a b c d Lyle, Paul (2010) [Between Rocks and Hard Places: Discovering Ireland's Northern Landscapes], HMSO, Belfast

- ^ List of Scheduled Monuments 2007, Department of the Environment NI

- ^ The Anglo-Normans in Ireland, Department of the Environment NI, Northern Ireland Environment Agency

- ^ a b Ballycastle Museum Archive, Ballycastle

- ^ BBC Northern Ireland, Your Place Or Mine, Marconi

- ^ Marconi Cottage has gone on the market (30 Sept 2009) Ballymoney and Moyle Times

- ^ Ash Rare Books, Antique Prints of Northern Ireland

- ^ The Scenery and Antiquities of Ireland, c 1841, J. Stirling Coyne & N. P. Willis Section:Volume II, Chapter III-4, accessed via libraryireland

- ^ "Visiting". fairheadclimbers.com. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

External links[edit]

- The Northern Ireland Guide: Pictures and Information on Fair head and the Crannóg

- Fair Head Climbing

- 1932 travel poster of Fair Head by Paul Henry at Travel Posters Online

- Photographs of Craigfad by The Glens of Antrim Historical Society

Category:Climbing areas of Ireland Category:Headlands of County Antrim Category:Geology of Northern Ireland Category:Sills (geology)