User:Mr. Ibrahem/Sickle cell disease

| Sickle cell disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Sickle cell disorder |

| |

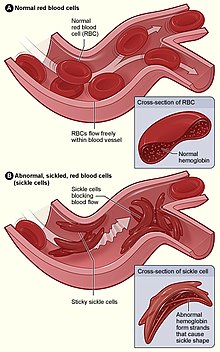

| Figure (A) shows normal red blood cells flowing freely through veins. The inset shows a cross section of a normal red blood cell with normal haemoglobin. Figure (B) shows abnormal, sickled red blood cells sticking at the branching point in a vein. The inset image shows a cross-section of a sickle cell with long polymerized sickle haemoglobin (HbS) strands stretching and distorting the cell shape to look like a crescent. | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

| Symptoms | Attacks of pain, anemia, swelling in the hands and feet, bacterial infections, stroke[1] |

| Complications | Chronic pain, stroke, aseptic bone necrosis, gallstones, leg ulcers, priapism, pulmonary hypertension, vision problems, kidney problems[2] |

| Usual onset | 5–6 months of age[1] |

| Causes | Genetic[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood test[4] |

| Treatment | Vaccination, antibiotics, high fluid intake, folic acid supplementation, pain medication, blood transfusions[5][6] |

| Prognosis | Life expectancy 40–60 years (developed world)[2] |

| Frequency | 4.4 million (2015)[7] |

| Deaths | 114,800 (2015)[8] |

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of blood disorders typically inherited from a person's parents.[2] The most common type is known as sickle cell anaemia (SCA).[2] It results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin found in red blood cells.[2] This leads to a rigid, sickle-like shape under certain circumstances.[2] Problems in sickle cell disease typically begin around 5 to 6 months of age.[1] A number of health problems may develop, such as attacks of pain ("sickle cell crisis"), anemia, swelling in the hands and feet, bacterial infections and stroke.[1] Long-term pain may develop as people get older.[2] The average life expectancy in the developed world is 40 to 60 years.[2]

Sickle cell disease occurs when a person inherits two abnormal copies of the β-globin gene that makes haemoglobin, one from each parent.[3] This gene occurs in chromosome 11.[9] Several subtypes exist, depending on the exact mutation in each haemoglobin gene.[2] An attack can be set off by temperature changes, stress, dehydration, and high altitude.[1] A person with a single abnormal copy does not usually have symptoms and is said to have sickle cell trait.[3] Such people are also referred to as carriers.[5] Diagnosis is by a blood test, and some countries test all babies at birth for the disease.[4] Diagnosis is also possible during pregnancy.[4]

The care of people with sickle cell disease may include infection prevention with vaccination and antibiotics, high fluid intake, folic acid supplementation, and pain medication.[5][6] Other measures may include blood transfusion and the medication hydroxycarbamide (hydroxyurea).[6] A small percentage of people can be cured by a transplant of bone marrow cells.[2]

As of 2015, about 4.4 million people have sickle cell disease, while an additional 43 million have sickle cell trait.[7][10] About 80% of sickle cell disease cases are believed to occur in Sub-Saharan Africa.[11] It also occurs relatively frequently in parts of India, the Arabian Peninsula, and among people of African origin living in other parts of the world.[12] In 2015, it resulted in about 114,800 deaths.[8] The condition was first described in the medical literature by American physician James B. Herrick in 1910.[13][14] In 1949, its genetic transmission was determined by E. A. Beet and J. V. Neel.[14] In 1954, the protective effect against malaria of sickle cell trait was described.[14]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Sickle Cell Disease?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. June 12, 2015. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "What Is Sickle Cell Disease?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. June 12, 2015. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b c "What Causes Sickle Cell Disease?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. June 12, 2015. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b c "How Is Sickle Cell Disease Diagnosed?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. June 12, 2015. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b c "Sickle-cell disease and other haemoglobin disorders Fact sheet N°308". January 2011. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b c "How Is Sickle Cell Disease Treated?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. June 12, 2015. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b GBD 2015 Disease Injury Incidence Prevalence Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

{{cite journal}}:|author1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b GBD 2015 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

{{cite journal}}:|author1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Learning About Sickle Cell Disease". National Human Genome Research Institute. May 9, 2016. Archived from the original on January 4, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators (August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

{{cite journal}}:|author1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT (December 2010). "Sickle-cell disease". Lancet. 376 (9757): 2018–31. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61029-x. PMID 21131035.

- ^ Elzouki, Abdelaziz Y. (2012). Textbook of clinical pediatrics (2 ed.). Berlin: Springer. p. 2950. ISBN 9783642022012. Archived from the original on 2020-08-19. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- ^ Savitt TL, Goldberg MF (January 1989). "Herrick's 1910 case report of sickle cell anemia. The rest of the story". JAMA. 261 (2): 266–71. doi:10.1001/jama.261.2.266. PMID 2642320.

- ^ a b c Serjeant GR (December 2010). "One hundred years of sickle cell disease". British Journal of Haematology. 151 (5): 425–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08419.x. PMID 20955412.