User:CaveatLector2022/History of climate change science

When it is assumed that the CO2 content of the atmosphere is doubled and statistical thermal equilibrium is achieved, the more realistic of the modeling efforts predict a global surface warming of between 2 °C and 3.5 °C, with greater increases at high latitudes. ... we have tried but have been unable to find any overlooked or underestimated physical effects that could reduce the currently estimated global warmings due to a doubling of atmospheric CO2 to negligible proportions or reverse them altogether.

Consensus begins to form, 1980–1988[edit]

By the early 1980s, the slight cooling trend from 1945 to 1975 had stopped. Aerosol pollution had decreased in many areas due to environmental legislation and changes in fuel use, and it became clear that the cooling effect from aerosols was not going to increase substantially while carbon dioxide levels were progressively increasing.

Hansen and others published the 1981 study Climate impact of increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide, and noted:

It is shown that the anthropogenic carbon dioxide warming should emerge from the noise level of natural climate variability by the end of the century, and there is a high probability of warming in the 1980s. Potential effects on climate in the 21st century include the creation of drought-prone regions in North America and central Asia as part of a shifting of climatic zones, erosion of the West Antarctic ice sheet with a consequent worldwide rise in sea level, and opening of the fabled Northwest Passage.[1]

In 1982, Greenland ice cores drilled by Hans Oeschger, Willi Dansgaard, and collaborators revealed dramatic temperature oscillations in the space of a century in the distant past.[2] The most prominent of the changes in their record corresponded to the violent Younger Dryas climate oscillation seen in shifts in types of pollen in lake beds all over Europe. Evidently drastic climate changes were possible within a human lifetime.

In 1973 James Lovelock speculated that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) could have a global warming effect. In 1975 V. Ramanathan found that a CFC molecule could be 10,000 times more effective in absorbing infrared radiation than a carbon dioxide molecule, making CFCs potentially important despite their very low concentrations in the atmosphere. While most early work on CFCs focused on their role in ozone depletion, by 1985 Ramanathan and others showed that CFCs together with methane and other trace gases could have nearly as important a climate effect as increases in CO2. In other words, global warming would arrive twice as fast as had been expected.[3]

In 1985 a joint UNEP/WMO/ICSU Conference on the "Assessment of the Role of Carbon Dioxide and Other Greenhouse Gases in Climate Variations and Associated Impacts" concluded that greenhouse gases "are expected" to cause significant warming in the next century and that some warming is inevitable.[4]

Meanwhile, ice cores drilled by a Franco-Soviet team at the Vostok Station in Antarctica showed that CO2 and temperature had gone up and down together in wide swings through past ice ages. This confirmed the CO2-temperature relationship in a manner entirely independent of computer climate models, strongly reinforcing the emerging scientific consensus. The findings also pointed to powerful biological and geochemical feedbacks.[5]

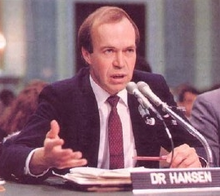

In June 1988, James E. Hansen made one of the first assessments that human-caused warming had already measurably affected global climate.[6] Shortly after, a "World Conference on the Changing Atmosphere: Implications for Global Security" gathered hundreds of scientists and others in Toronto. They concluded that the changes in the atmosphere due to human pollution "represent a major threat to international security and are already having harmful consequences over many parts of the globe," and declared that by 2005 the world would be well-advised to push its emissions some 20% below the 1988 level.[7]

The 1980s saw important breakthroughs with regard to global environmental challenges. Ozone depletion was mitigated by the Vienna Convention (1985) and the Montreal Protocol (1987). Acid rain was mainly regulated on national and regional levels.

Modern period: 1988 to present[edit]

In 1988 the WMO established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change with the support of the UNEP. The IPCC continues its work through the present day, and issues a series of Assessment Reports and supplemental reports that describe the state of scientific understanding at the time each report is prepared. Scientific developments during this period are summarized about once every five to six years in the IPCC Assessment Reports which were published in 1990 (First Assessment Report), 1995 (Second Assessment Report), 2001 (Third Assessment Report), 2007 (Fourth Assessment Report), 2013/2014 (Fifth Assessment Report). and 2021 Sixth Assessment Report[12] The 2001 report was the first to state positively that the observed global temperature increase was "likely" to be due to human activities. The conclusion was influenced especially by the so-called hockey stick graph showing an abrupt historical temperature rise simultaneous with the rise of greenhouse gas emissions, and by observations of changes in ocean heat content that had a "signature" matching the pattern that computer models calculated for the effect of greenhouse warming. By the time of the 2021 report, scientists had much additional evidence. Above all, measurements of paleotemperatures from several eras in the distant past, and the record of temperature change since the mid 19th century, could be matched against measurements of CO2 levels to provide independent confirmation of supercomputer model calculations.

These developments depended crucially on huge globe-spanning observation programs. Since the 1990s research into historical and modern climate change expanded rapidly. International coordination was provided by the World Climate Research Programme (established in 1980) and was increasingly oriented around providing input to the IPCC reports. Measurement networks such as the Global Ocean Observing System, Integrated Carbon Observation System, and NASA's Earth Observing System enabled monitoring of the causes and effects of ongoing change. Research also broadened, linking many fields such as Earth sciences, behavioral sciences, economics, and security.

- ^ Hansen, J.; et al. (1981). "Climate impact of increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide". Science. 231 (4511): 957–966. Bibcode:1981Sci...213..957H. doi:10.1126/science.213.4511.957. PMID 17789014. S2CID 20971423.

- ^ Dansgaard W.; et al. (1982). "A New Greenland Deep Ice Core". Science. 218 (4579): 1273–77. Bibcode:1982Sci...218.1273D. doi:10.1126/science.218.4579.1273. PMID 17770148. S2CID 35224174.

- ^ Spencer Weart (2003). "Other Greenhouse Gases". The Discovery of Global Warming.

- ^ World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) (1986). "Report of the International Conference on the assessment of the role of carbon dioxide and of other greenhouse gases in climate variations and associated impacts". Villach, Austria. Archived from the original on 21 November 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ^ Lorius Claude; et al. (1985). "A 150,000-Year Climatic Record from Antarctic Ice". Nature. 316 (6029): 591–596. Bibcode:1985Natur.316..591L. doi:10.1038/316591a0. S2CID 4368173.

- ^ "Statement of Dr. James Hansen, Director, NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies" (PDF). The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ^ WMO (World Meteorological Organization) (1989). The Changing Atmosphere: Implications for Global Security, Toronto, Canada, 27–30 June 1988: Conference Proceedings (PDF). Geneva: Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-06-29.

- ^ Cook, John; Oreskes, Naomi; Doran, Peter T.; Anderegg, William R. L.; et al. (2016). "Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming". Environmental Research Letters. 11 (4): 048002. Bibcode:2016ERL....11d8002C. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002.

- ^ Powell, James Lawrence (20 November 2019). "Scientists Reach 100% Consensus on Anthropogenic Global Warming". Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. 37 (4): 183–184. doi:10.1177/0270467619886266. S2CID 213454806. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ Lynas, Mark; Houlton, Benjamin Z.; Perry, Simon (19 October 2021). "Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (11): 114005. Bibcode:2021ERL....16k4005L. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966. S2CID 239032360.

- ^ Myers, Krista F.; Doran, Peter T.; Cook, John; Kotcher, John E.; Myers, Teresa A. (20 October 2021). "Consensus revisited: quantifying scientific agreement on climate change and climate expertise among Earth scientists 10 years later". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (10): 104030. Bibcode:2021ERL....16j4030M. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2774. S2CID 239047650.

- ^ "IPCC – Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change". ipcc.ch.