User:AKALIA23/Pausanias (geographer)

Pausanias (/pɔːˈseɪniəs/; Greek: Παυσανίας Pausanías; c. 110 – c. 180 CE[1]) was a Greek traveller and geographer of the second century CE. He is famous for his Description of Greece (Ancient Greek: Ἑλλάδος Περιήγησις, Hellados Periegesis),[2] a lengthy work that describes ancient Greece from his firsthand observations. Description of Greece provides crucial information for making links between classical literature and modern archaeology.

Biography of Pausanias[edit]

Not much is known about Pausanias apart from what historians can piece together from his own writing. However, it is mostly certain that he was born c. 110 CE into a Greek family and was probably a native of Lydia in Asia Minor.[3] From c. 150 CE until his death in 180, Pausanias travelled through the mainland of Greece, writing about various monuments, sacred spaces, and significant geographical sites along the way. In writing Description of Greece, Pausanias sought to put together a lasting written account of “all things Greek,” or "panta ta hellenika."[4]

Living in the Roman Empire[edit]

Despite being born in Asia Minor, Pausanias belonged to a Greek family and was of Greek heritage.[5] However, he grew up and lived under the rule of the Roman Empire. Although Pausanias was a subordinate of the Roman Empire, he nonetheless valued his Greek identity, history, and culture: he was keen to describe the glories of a Greek past that still was relevant in his lifetime, even if the country was beholden to Rome as a dominating imperial force. Pausanias’ pilgrimage through the land of his ancestors was his own attempt to establish a place in the world for this new Roman Greece, connecting myths and stories of ancient culture to those of his own time.[6]

Travel[edit]

Although Pausanias is known for his travels throughout the Greek mainland, he also journeyed to various regions and countries beyond Greece. Since he grew up in Asia Minor, he began his traveling there, visiting sites near Mount Sipylos. He also explored other cities in the Middle East such as Jerusalem and Antioch, in addition to natural phenomena like the River Jordan. In his trip to Egypt, he saw the pyramids and visited the temple of Amon at Siwah. He also toured Macedonia, Italy (Rome and Campania, in particular), and the ruins of Troy and Mycenae.[7]

Writing Style[edit]

Pausanias has a noticeably straightforward and simple way of writing. He is, overall, direct in his language, writing his stories and descriptions in an unelaborate style. However, some translators have noted that Pausanias' use of various prepositions and tenses are confusing and difficult to render in English. For example, Pausanias may use a past tense verb rather than the present tense in some instances. It is thought that he did this in order to make himself seem to be in the same temporal setting as his audience.[8]

Additionally, unlike in a traditional travel guide, in Description of Greece, Pausanias tends to digress to discuss a point of an ancient ritual or to tell a myth that goes along with the site he is visiting. This style of writing would not become popular again until the early nineteenth century.[9] In the topographical aspect of his work, Pausanias makes many digressions on the wonders of nature, the signs that herald the approach of an earthquake, the phenomena of the tides, the ice-bound seas of the north, and the noonday sun that at the summer solstice casts no shadow at Syene (Aswan). While he never doubts the existence of the deities and heroes, he sometimes criticizes the myths and legends relating to them. His descriptions of monuments of art are plain and unadorned, bearing a solid impression of reality.[10]

Pausanias is also frank in his confessions of ignorance. When he quotes a book at second hand rather than relating his own experiences, he is honest about his sourcing.[11]

Description of Greece (Hellados Periegesis)[edit]

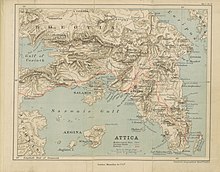

Pausanias' Description of Greece comprises ten books, each dedicated to some portion of Greece. He begins his tour in Attica (Ἀττικά), where the city of Athens and its demes dominate the discussion. Subsequent books describe Corinthia (Κορινθιακά), Laconia (Λακωνικά), Messenia (Μεσσηνιακά), Elis (Ἠλιακῶν), Achaea (Ἀχαικά), Arcadia (Ἀρκαδικά), Boetia (Βοιωτικά), Phocis (Φωκικά), and Ozolian Locris (Λοκρῶν Ὀζόλων).[12] The project is more than topographical: it is a cultural geography of Greece. Pausanias does not only describe architectural and artistic objects, but also reviews the mythological and historical underpinnings of the society that produced them.[13]

Although Pausanias was not a naturalist by trade, he does tend to comment on the physical aspects of the Greek landscape. He notices the pine trees on the sandy coast of Elis, the deer and the wild boars in the oak woods of Phelloe, and the crows amid the giant oak trees of Alalcomenae. Towards the end of Description of Greece, Pausanias touches on the products and fruits of nature, such as the wild strawberries of Helicon, the date palms of Aulis, the olive oil of Tithorea, as well as the tortoises of Arcadia and the "white blackbirds" of Cyllene.

Additionally, Pausanias was heavily motivated by his interest in religion: in fact, his Description of Greece has been regarded as a "journey into identity,"[14] referring to that of his Greek heritage and beliefs. Pausanias describes the religious art and architecture of many famous sacred sites such as Olympia and Delphi. However, even in the most remote regions of Greece, he is fascinated by all kinds of depictions of deities, holy relics, and many other sacred and mysterious objects. For example, at Thebes, he views the shields of those who died at the Battle of Leuctra, the ruins of the house of Pindar, and the statues of Hesiod, Arion, Thamyris, and Orpheus in the grove of the Muses on Helicon, as well as the portraits of Corinna at Tanagra and of Polybius in the cities of Arcadia.[15]

Pausanias was mostly interested in relics of antiquity, rather than contemporary architecture or sacred spaces. As Christian Habicht, a contemporary classicist who wrote a multitude of scholarly articles on Pausanias, says:

In general, he prefers the old to the new, the sacred to the profane; there is much more about classical than about contemporary Greek art, more about temples, altars and images of the gods, than about public buildings and statues of politicians.[16]

The end of Description of Greece remains mysterious: some believe that Pausanias died before finishing his work,[17] and others believe his strange ending was intentional. He concludes his Periegesis with a story about a Greek author, thought to be Anyte of Tegea, who has a divine dream. In the dream, she is told to present the text of Description of Greece to a wider Greek audience in order to open their eyes to "all things Greek."[18]

Different Translations[edit]

Pausanias’ Description of Greece has been translated into English by several different scholars over time. A widely known version of the text is available through the Loeb Classical Library and was translated by William Henry Samuel James. The Loeb Classical Library offers translations of Greek and Latin texts in a manner that is accessible to those who have knowledge of the languages and even those who do not. Translations are provided in English. The W.H.S. James translation of Description of Greece comes in five volumes with the ancient Greek text included. It also includes an introduction that summarizes the contents of each book.[19] Additionally, Description of Greece was translated by Peter Levi. This translation is also popular among English speakers, but is often thought to be a loose translation of the original text: Levi took liberties with his translation that restructured Description of Greece to function like a general guidebook to mainland Greece, which was not Pausanias’ original intention.[20] Sir James George Frazer also published six volumes of translation and commentary of Description of Greece; his translation remains a credible work of scholarship to readers of Pausanias today.[21]

Lost in History[edit]

Description of Greece left very faint traces in the known Greek corpus. "It was not read," Habicht relates, "there is not a single mention of the author, not a single quotation from it, not a whisper before Stephanus Byzantius in the sixth century, and only two or three references to it throughout the Middle Ages."[22] The only surviving manuscripts of Pausanias are three fifteenth-century copies, full of errors and lacunae, which all appear to depend on a single manuscript that managed to be copied. Niccolò Niccoli, a collector of manuscripts from antiquity, had this archetype in Florence around 1418. After his death in 1437, it was sent to the library of San Marco, Florence, ultimately disappearing after 1500.[23]

Modern Views of Pausanias[edit]

Until the twentieth-century, when archaeologists concluded that Pausanias was a reliable guide to the sites they were excavating, Pausanias was largely dismissed by classicists of a purely literary bent: they tended to follow their usually authoritative contemporary Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, regarding him as little more than a purveyor of second-hand accounts. They also believed Pausanias had not visited most of the places he described. Modern archaeological research, however, has tended to vindicate Pausanias.[24]

Additionally, there have been a multitude of scholars who have sought to discover the truth about Pausanias and his Description of Greece. Many books, commentaries, and scholarly articles have been written on this ancient figure, and Pausanias' recorded travels still serve as a tool to understanding the relationship between archaeology, mythology, and history.[25]

Bibliography[edit]

- Diller, Aubrey. 1957. "The Manuscripts of Pausanias." Transactions of the American Philological Association 88:169–188.

- Elsner, John. “Pausanias: A Greek Pilgrim in the Roman World.” Past & Present 135, no. 1 (May 1992): 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/past/135.1.3.

- Fowler, Harold N. “Pausanias’s Description of Greece.” American Journal of Archaeology 2, no. 5 (1898): 357–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/496590.

- Habicht, Christian. “An Ancient Baedeker and His Critics: Pausanias’ ‘Guide to Greece.’” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 129, no. 2 (1985): 220–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/986990.

- Habicht, Christian. “Pausanias and the Evidence of Inscriptions.” Classical Antiquity 3, no. 1 (April 1984): 40–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/25010806.

- Habicht, C. 1998. Pausanias’ Guide to Ancient Greece. 2d ed. Sather Classical Lectures 50. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

- Howard, Michael C. (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: The Role of Cross-Border Trade and Travel. McFarland. p. 178.

- Hutton, William. Describing Greece: Landscape and Literature in the Periegesis of Pausanias. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Jacob, Christian, and Anne Mullen-Hohl. “The Greek Traveler’s Areas of Knowledge: Myths and Other Discourses in Pausanias’ Description of Greece.” Yale French Studies, no. 59 (1980): 65–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/2929815.

- MacCormack, S. (2010-11-01). "Pausanias and his commentator Sir James George Frazer". Classical Receptions Journal. 2 (2): 287–313. doi:10.1093/crj/clq010. ISSN 1759-5134.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. Translated by Jones W H S. 5. Vol. 1. 5 vols. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1918.

- Sidebottom, H. “Pausanias: Past, Present, and Closure.” The Classical Quarterly 52, no. 2 (2002): 494–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/cq/52.2.494

Further Reading[edit]

- Alcock, Susan E., John F. Cherry, and Elsner Jaś. Pausanias: Travel and Memory in Roman Greece. Google Books. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Arafat, K.W. 1992. "Pausanias' Attitude to Antiquities." Annual of the British School at Athens 87: 387–409.

- Akujärvi, J. 2005. Researcher, Traveller, Narrator: Studies in Pausanias’ Periegesis. Studia graeca et latina lundensia 12. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Arafat, K. 1996. Pausanias’ Greece: Ancient Artists and Roman Rulers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Diller, Aubrey. “Pausanias in the Middle Ages.” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 87 (1956): 84–97. https://doi.org/10.2307/283874.

- Dunn, Francis M. “Pausanias on the Tomb of Medea’s Children.” Mnemosyne 48, no. 3 (1995): 348–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4432507.

- Hutton, W. E. 2005. Describing Greece: Landscape and Literature in the Periegesis of Pausanias. Greek Culture in the Roman World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Peter Levi, Guide to Greece (vol. 1: Northern Greece; vol. 2: Southern Greece), Penguin Classics, 1971.

- Pausanias Description of Greece, tr. with a commentary by J.G. Frazer (1898) Volume 1 (also at the Internet Archive)

- Pirenne-Delforge, V. 2008. Retour à la Source: Pausanias et la Religion Grecque. Kernos Supplément 20. Liège, Belgium: Centre International d‘Étude de la Religion Grecque.

- Pretzler, Maria. 2005. "Pausanias and Oral Tradition." Classical Quarterly 55.1: 235–249.

- Pretzler, M. 2007. Pausanias: Travel Writing in Ancient Greece. Classical Literature and Society. London: Duckworth.

- Pretzler, Maria. 2004, "Turning Travel into Text: Pausanias at Work" Greece & Rome 51.2: 199–216.

- Sanchez Hernandez, Juan Pablo. 2016. "Pausanias and Rome's Eastern Trade." Mnemosyne 69.6: 955–977.

Citations, Notes, and References[edit]

- ^ Historical and Ethnological Society of Greece, Aristéa Papanicolaou Christensen, The Panathenaic Stadium – Its History Over the Centuries (2003), p. 162

- ^ Also known in Latin as Graecae descriptio; see Pereira, Maria Helena Rocha (ed.), Graecae descriptio, B. G. Teubner, 1829.

- ^ Howard, Michael C. (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: The Role of Cross-Border Trade and Travel. McFarland. p. 178. ISBN 9780786490332.

Pausanias was a 2nd century ethnic Greek geographer who wrote a description of Greece that is often described as being the world’s first travel guide.

- ^ Frazer, Pausanias's Description, i. p. xxii; Sidebottom, H. “Pausanias: Past, Present, and Closure.” The Classical Quarterly 52, no. 2 (2002): pp.499. https://doi.org/10.1093/cq/52.2.494.

- ^ Pausanias. Description of Greece. Translated by Jones W H S. Vol. 1. pp. ix-x. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1918.

- ^ Elsner, John. “Pausanias: A Greek Pilgrim in the Roman World.” Past & Present 135, no. 1 (May 1992): pp. 3-5. https://doi.org/10.1093/past/135.1.3.

- ^ Peter Levi, Guide to Greece (vol. 1: Northern Greece; vol. 2: Southern Greece), Penguin Classics, 1971.

- ^ Pausanias. Description of Greece. Translated by Jones W H S. 5. Vol. 1. pp. x-xi. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1918.

- ^ Elsner, John. “Pausanias: A Greek Pilgrim in the Roman World.” Past & Present 135, no. 1 (May 1992): pp.10. https://doi.org/10.1093/past/135.1.3.

- ^ Pausanias. Description of Greece. Translated by Jones W H S. 5. Vol. 1. pp. ix. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1918.

- ^ Pausanias. Description of Greece. Translated by Jones W H S. 5. Vol. 1. pp. x. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1918.

- ^ Pausanias. Description of Greece. Translated by Jones W H S. 5. Vol. 1-5. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1918. Further Reading

- ^ Habicht, Christian. “Pausanias and the Evidence of Inscriptions.” Classical Antiquity 3, no. 1 (April 1984): pp 41-46. https://doi.org/10.2307/25010806.

- ^ Elsner, John. “Pausanias: A Greek Pilgrim in the Roman World.” Past & Present 135, no. 1 (May 1992): pp.12. https://doi.org/10.1093/past/135.1.3.

- ^ Pausanias. Description of Greece. Translated by Jones W H S. 5. Vol. 1-5. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1918.

- ^ Christian Habicht, "An Ancient Baedeker and His Critics: Pausanias' 'Guide to Greece'" Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 129.2 (June 1985:220–224) p. 220.

- ^ Habicht, C. 1998. Pausanias’ Guide to Ancient Greece. 2d ed. Sather Classical Lectures 50. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

- ^ Sidebottom, H. “Pausanias: Past, Present, and Closure.” The Classical Quarterly 52, no. 2 (2002): pp. 499. https://doi.org/10.1093/cq/52.2.494

- ^ Pausanias. Description of Greece. Translated by Jones W H S. 5. Vol. 1-5. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1918.

- ^ Elsner, John (1992). "PAUSANIAS: A GREEK PILGRIM IN THE ROMAN WORLD". Past and Present. 135 (1): 3–29. doi:10.1093/past/135.1.3. ISSN 0031-2746.

- ^ MacCormack, S. (2010-11-01). "Pausanias and his commentator Sir James George Frazer". Classical Receptions Journal. 2 (2): 287–313. doi:10.1093/crj/clq010. ISSN 1759-5134.

- ^ Habicht, Christian. “An Ancient Baedeker and His Critics: Pausanias’ ‘Guide to Greece.’” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 129, no. 2 (1985): 220–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/986990.

- ^ Diller, A. 1957. "The Manuscripts of Pausanias." Transactions of the American Philological Association 88:169–188.

- ^ Christian Habicht, "An Ancient Baedeker and His Critics: Pausanias' 'Guide to Greece'" Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 129.2 (June 1985:220–224) p. 220.

- ^ Habicht, Christian. “Pausanias and the Evidence of Inscriptions.” Classical Antiquity 3, no. 1 (April 1984): pp. 55-56. https://doi.org/10.2307/25010806.