Temple of Juno Moneta

Drawing of the Capitoline Hill by Georg Rehlender, with the Temple of Juno Moneta at upper right, above the Tabularium. | |

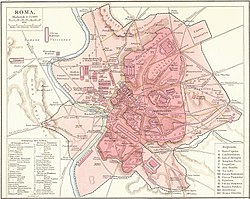

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Location | Regione VIII Forum Romanum |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°53′36″N 12°29′1″E / 41.89333°N 12.48361°E |

| Type | Temple |

| History | |

| Builder | Lucius Furius Camillus |

| Founded | 344 BC[1] |

The Temple of Juno Moneta (Latin: Templum Iunonis Monetæ) was an ancient Roman temple that stood on the Arx or the citadel on the Capitoline Hill overlooking the Roman Forum.[2] Located at the center of the city of Rome, it was next to the place where Roman coins were first minted, and probably stored the metal and coins involved in this process, thereby initiating the ancient practice of associating mints with temples.[3] In addition, it was the place where the books of the magistrates were deposited.

Etymology[edit]

Juno Moneta, the second name associating the Roman goddess Juno with the goddess Moneta who was worshiped at some locations outside Rome, was regarded as the protectress of the city's funds. Money was coined in her temple for over four centuries, before the mint was moved to a new location near the Colosseum during the reign of emperor Domitian.[1] Thus, moneta came to mean "mint" (mint itself being a corruption of moneta) in Latin, which was used in written works of ancient Roman writers such as Ovid, Martial, Juvenal, and Cicero, and was the origin of the English words "monetary" and "money".

Cicero suggests that the name Moneta derived from the verb "monere" (to warn) because during an earthquake, a voice from this temple had demanded the expiatory sacrifice of a pregnant sow, connecting to the old Roman legend that Juno's sacred geese warned the Roman commander Marcus Manlius Capitolinus of the approach of the Gauls in 390 BC.[2] But modern scholars reject this explanation, because it is clear that "Moneta" was the name of a goddess who was worshiped in some places outside Rome, and when her worship was transferred to Rome, she was equated with Juno.

Moneta is also a name used for Mnemosyne, mother of the Muses, by Livius Andronicus in his translation of the Odyssey, and Hyginus' citation of Jupiter and Moneta as parents of the muses. The name Mnemosyne or Memory was connected to Juno Moneta who maintained in her temple an unimpeachable record of historical events.[2]

History[edit]

In the beginning of the hostilities with the Aurunci in 345 BC, Camillus decided to summon the aid of the gods for the conflict by vowing to build a temple to Juno Moneta. While victoriously returning to Rome, he resigned from his post and the senate appointed two commissioners to build the temple. They chose its site to be on the citadel, where the house of Marcus Manlius Capitolinus had been, and dedicated it one year after the vow.[1] This was recorded in Livy's History of Rome and Ovid's Fasti, where the latter states:[4]

|

|

The temple stored the Libri Lintei, the records of annually elected consuls, dating from 444 BC to 428 BC. From 273 BC, Roman silver mint and its workshops were attached to the temple. Moneta's guardianship of Roman coinage encouraged Roman moneyers to use this means as a true record for glorifying their families by commemorating heroic family legends.[2]

If still in use by the 4th-century, it would have been closed during the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire.

According to legend, it was here that the Roman sibyl foretold the coming of Christ to the emperor Augustus, who was granted a heavenly vision of the Virgin Mary standing on an altar holding the Christ child. Augustus supposedly built an altar on the spot – the altar of heaven or ara coeli – and the church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli rose around it. The original structure cannot possibly date back to the time of Augustus (Rome did not become officially Christian until the 4th century), but by the 6th century the existing church was already considered old. It was later rebuilt, with the present structure dating from the 13th century.[6]

Location[edit]

Due to lack of vestiges and scarce information concerning the exact location, the temple is considered to be an enigma in the topography of ancient Rome. However, all agree on the fact that it stood on the summit of the citadel rather than on the other two areas of the hill. Some topographers placed the temple's location under the church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli, while others placed it close to the edge of the hill facing the Forum alongside the stairway up to the back of the church.[1]

Although tradition talks about the construction of the temple on the site of the house of the patrician hero Manlius,[1] ancient sources, in reference to the period of the Gallic Wars of 390 BC, suggest the existence of a previous temple building, which was linked to two found Archaic terracotta artefacts in the Aracoeli garden dating to the period between late 4th and early 5th centuries. Other remains of square walls and stones which were preserved in the garden, were attributed by scholars to the fortification work of the Arx, possibly going back to the supposed Archaic and Mid-Republican phases of the Temple.[7]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Peter J. Aicher, Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, (2004). Rome Alive: A Source-Guide to the Ancient City, Volume 1 p.66-68.

- ^ a b c d Littlewood, R. Joy (2006). A Commentary on Ovid's Fasti, Book 6. Oxford University Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-19-156920-8.

- ^ Taylor, Mark C. (1 November 1992). Disfiguring: Art, Architecture, Religion. University of Chicago Press. p. 146. ISBN 9780226791326.

- ^ William Smith, Walton & Maberly, (1857). Dictionary of Greek and Roman geography, Volume 2 p.766.

- ^ Ovid, Notes & Introduction: Thomas Keightley, Richard Miliken and Son, 1833. Ovid's Fasti p.229.

- ^ George H. Sullivan, Da Capo Press, (2006). Not Built in a Day: Exploring The Architecture of Rome p. 33. ISBN 0-78-671749-1

- ^ The Temple of Juno Moneta, Ancient Capitol Musei Capitolini Archived 2012-01-14 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on April 17, 2012.