Temple of Concord

| |

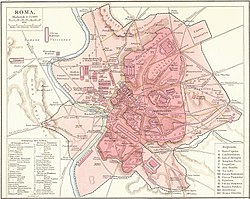

| Location | Regio VIII Forum Romanum |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°53′35″N 12°29′03″E / 41.89293°N 12.484245°E |

| Type | Roman Temple |

| History | |

| Builder | Unknown |

| Founded | 4th Century BC |

The Temple of Concord (Latin: Aedes Concordiae) in the ancient city of Rome refers to a series of shrines or temples dedicated to the Roman goddess Concordia, and erected at the western end of the Roman Forum. The earliest temple is believed to have been vowed by Marcus Furius Camillus in 367 BC, but it may not have been built until 218 BC by L. Manlius. The temple was rebuilt in 121 BC, and again by the future emperor Tiberius between 7 BC and AD 10.

History[edit]

One tradition ascribes the first Temple of Concord to a vow made by Camillus in 367 BC, on the occasion of the Lex Licinia Sextia, the law passed by the tribunes Gaius Licinius Stolo and Lucius Sextius Lateranus, opening the consulship to the plebeians. The two had prevented the election of any magistrates for a period of several years, as part of the conflict of the orders. Nominated dictator to face an invasion of the Gauls, Camillus, encouraged by his fellow patrician Marcus Fabius Ambustus, Stolo's father-in-law, determined to resolve the crisis by declaring his support for the law, and vowing a temple to Concordia, symbolizing reconciliation between the patricians and plebeians.[1][2]

Camillus' vow is not mentioned by Livy, who instead describes the dedication of the Temple of Concord in the Vulcanal, a precinct sacred to Vulcan on the western end of the forum, by the aedile Gnaeus Flavius in 304 BC. Flavius' actions were an affront to the senate, partly because he had undertaken the matter without first consulting them, and partly because of his low social standing: not only was Flavius a plebeian, but he was the son of a freedman, and had previously served as a scribe to Appius Claudius Caecus. The Pontifex Maximus, Rome's chief priest, was compelled to instruct Flavius on the proper formulae for dedicating a temple.[3] Cicero and Pliny report that Flavius was a scribe, rather than aedile, at the time of the dedication,[4][5] and a law was passed immediately afterward forbidding anyone from dedicating a temple without the authorization of the senate or a majority of the plebeian tribunes.[3]

Yet a third Temple of Concord was begun in 217 BC, early in the Second Punic War, by the duumviri Marcus Pupius and Caeso Quinctius Flamininus, in fulfillment of a vow made by the praetor Lucius Manlius Vulso on the occasion of his deliverance from the Gauls in 218. The reason why Manlius vowed a temple to Concordia is not immediately apparent, but Livy alludes to a mutiny that had apparently occurred among the praetor's men. The temple was completed and dedicated the following year by the duumviri Marcus and Gaius Atilius.[6]

The murder of Gaius Gracchus in 121 BC marked a low point in the relationship between the emerging Roman aristocracy and the popular party, and was immediately followed by the reconstruction of the Temple of Concord by Lucius Opimius at the senate's behest, which was regarded as an utterly insincere attempt to clothe its actions in a symbolic act of reconciliation.[7][8][9][10]

From this period, the temple was frequently used as a meeting place for both the Senate and the Arval Brethren.[11][12][13][14] Two important Senate meetings, including one in which Cicero delivered his Fourth Catilinarian speech and another in which Sejanus was condemned to death, took place in the Temple of Concord.[15]

A statue of Victoria placed on the roof of the temple was struck by lightning in 211 BC, and prodigies were reported in the Concordiae, the neighborhood of the temple, in 183 and 181.[16][17] Little else is heard of the temple until 7 BC, when the future emperor Tiberius undertook another restoration, which lasted until AD 10, when the structure was rededicated on 16 January as the Aedes Concordiae Augustae, the Temple of Concordia of Augustus.[18][19][20]

This new temple served as a museum for a number of works of art, many of which are described by Pliny.[21] The fine collection consisted primarily of Greek art including a statue of Hestia, several group bronzes, and panel paintings by famous Greek painters including Zeuxis, Nikias and Theoros.[22]

The temple is occasionally mentioned in imperial times, and it could have been the meeting place of the Senate after the death of Gordian I and II when Pupienus and Balbinus were elected as emperors [23][24] and may have been restored again following a fire in AD 284.[25] If still in use, the temple would have been closed during the persecution of pagans under the Christian emperors of the late fourth century. The building, however, remained standing. By the eighth century, the temple was reportedly in poor condition, and in danger of collapsing.[14]

The temple was razed circa 1450, and the stone turned into a lime kiln to recover the marble for building.[26]

Architecture[edit]

The Temple of Concord, constructed by Lucius Opimus during the Republican period, had a typical rectangular podium (40.8m x 30m). Based on the construction methods used in the base and support walls, the porch had eight Corinthian columns made out of travertine drums covered in stucco.[27]

The later construction of the Temple of Concordia Augusta expanded and altered the previous temple. Backed up against the Tabularium at the foot of the Capitoline Hill, the design of the temple had to accommodate the limitations of the site. The cella of the temple, for instance, is almost twice as wide (45m) as it is deep (24m), as is the pronaos. A steep flight of stairs led up to the entrance of the temple on the long side, which would have been flanked by statues of Hercules and Mercury, symbolizing security and prosperity.[28] A fragment of the marble threshold of the cella is preserved and features an engraved caduceus or wand of Mercury, which represented peace and reconciliation.[15] Three statues were positioned on the apex of the pediment, which represented Concord along with two other goddess, Pax and Salus (or Securitas and Fortuna).[28] Two soldiers, representing Tiberius and his brother Drusus, stood on either side of them.[28] In the cella, a row of Corinthian columns rose from a continuous plinth projecting from the wall, which divided the cella into bays, each containing a niche. The capitals of these columns had pairs of leaping rams in place of the corner volutes. Only the platform now remains, partially covered by a road up to the Capitol.

Other temples[edit]

The main temple in the Forum in Rome seems to have been a model for temples to the goddess elsewhere in the empire—a reproduction of this temple was found at Mérida in Spain, during the excavations of the town's forum in 2002.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Ovid, Fasti, i. 641–644.

- ^ Plutarch, "The Life of Camillus", 42.

- ^ a b Livy, ix. 46.

- ^ Cicero, Epistulae ad Atticum, vi. 1. § 8, Pro Murena, 25.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis, xxxiii. 17.

- ^ Livy, xxii. 33, xxiii. 21.

- ^ Appian, Bellum Civile, i. 26.

- ^ Plutarch, "The Life of Gaius Gracchus", 17.

- ^ Cicero, Pro Sestio, 140.

- ^ Augustine, De Civitate Dei, iii. 25.

- ^ Cicero, In Catilinam, iii. 21, Pro Sestio, 26, De Domo Sua, 111, Philippicae, ii. 19, 112, iii. 31, v. 18.

- ^ Sallust, Bellum Catilinae, 46, 49.

- ^ Cassius Dio, lviii. 2, 4.

- ^ a b Platner & Ashby, Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, s. v. Concordia, Aedes, Templum.

- ^ a b Coarelli, F. Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide. p. 67.

- ^ Livy, xxvi. 23, xxxix. 56, xl. 19.

- ^ Obsequens, Liber de Prodigiis, 4.

- ^ Ovid, Fasti, i. 640, 643–648

- ^ Cassius Dio, lvi. 25

- ^ Suetonius, "The Life of Tiberius", 20.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis, xxxiv. 73, 77, 80, 89, 90, xxxv. 66, 131, 144, 196, xxxvii. 4.

- ^ Claridge, Amanda. Rome: An Archaeological Guide. p. 81.

- ^ Historia Augusta. p. 166.

- ^ Edward, Gibbon. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. p. 195.

- ^ CIL VI, 89.

- ^ Lanciani, Pagan and Christian Rome, 53

- ^ The Roman Forum: A Reconstruction and Architectural Guide. p. 172.

- ^ a b c Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. p. 80.

Bibliography[edit]

- Marcus Tullius Cicero, De Domo Sua, Epistulae ad Atticum, In Catilinam, Philippicae, Pro Murena, Pro Sestio.

- Gaius Sallustius Crispus (Sallust), Bellum Catilinae (The Conspiracy of Catiline).

- Titus Livius (Livy), History of Rome.

- Publius Ovidius Naso (Ovid), Fasti.

- Gaius Plinius Secundus (Pliny the Elder), Historia Naturalis (Natural History).

- Plutarchus, Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans.

- Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, De Vita Caesarum (Lives of the Caesars, or The Twelve Caesars).

- Appianus Alexandrinus (Appian), Bellum Civile (The Civil War).

- Lucius Cassius Dio Cocceianus (Cassius Dio), Roman History.

- Julius Obsequens, Liber de Prodigiis (The Book of Prodigies).

- Augustine of Hippo, De Civitate Dei (The City of God).

- Theodor Mommsen et alii, Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (The Body of Latin Inscriptions, abbreviated CIL), Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften (1853–present).

- Rodolfo Lanciani, Pagan and Christian Rome, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston and New York (1892).

- Harper's Dictionary of Classical Literature and Antiquities, Harry Thurston Peck, ed. (Second Edition, 1897).

- Samuel Ball Platner & Thomas Ashby, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, Oxford University Press (1929).

- Claridge, Amanda. 2010. Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. 2nd ed., revised and expanded. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gorski, Gilbert, and James E. Packer. 2015. The Roman Forum: A Reconstruction and Architectural Guide. New York : Cambridge University Press.

- Coarelli, Filippo. 2007. Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Further reading[edit]

- Clark, Anna J. 2007. Divine Qualities. Cult and Community in Republican Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hillard, Tom. 2013. “Graffiti’s Engagement: The Political Graffiti of the Late Roman Republic.” In Written Space in the Latin West, 200 BC to AD 300 Edited by Gareth Sears, Peter Keegan and Ray Laurence, 105–122. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Packer, James E. 2010. "Pompey's Theater and Tiberius' Temple of Concord: A Late Republican Primer for an Early Imperial Patron." Yale Classical Studies 35: 135-167.

- Rebert, Homer F. and Henri Marceau. 1925. "The Temple of Concord in the Roman Forum." Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 5: 53-77.

- Stamper, John W. 2005. The Architecture of Roman Temples: The Republic to the Middle Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.