Chagga states

Chagga States and Kingdoms Uchaggani (Swahili) | |

|---|---|

| c.1600–6 December 1963 | |

Location of Chaggaland c.1891 | |

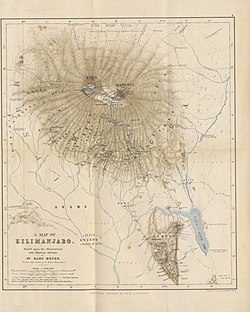

Map of Kilimanjaro showing 15 of the largest states as of 1964 | |

| Official languages | Chagga |

| Common languages | Chagga & Swahili |

| Religion | African traditional religions & Sunni Islam |

| Demonym(s) | Chaggan |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Mangi (King) | |

| History | |

• Established | c.1600 |

• Disestablished | 6 December 1963 |

| Area | |

• Total | 518[1] km2 (200 sq mi) |

| Currency | barter |

| Today part of | |

| Person | Mchaga |

|---|---|

| People | Wachaga |

| Language | Kichaga |

| Country | Dchaga |

The Chagga States or Chagga Kingdoms also historically referred to as the Chaggaland [2] (Uchaggani, in Swahili) were a pre-colonial series of a Bantu sovereign states of the Chagga people on Mount Kilimanjaro in modern-day northern Kilimanjaro Region of Tanzania.[3] The Chagga kingdoms existed as far back as the 17th century according to oral tradition,[4] a lot of recorded history of the Chagga states, was written with the arrival, and colonial occupation of Europeans in the mid to late 19th century.[5] On the mountain, many minor dialects of one language are divided into three main groupings that are defined geographically from west to east: West Kilimanjaro, East Kilimanjaro, and Rombo. One word they all have in common is Mangi, meaning king in Kichagga.[6] The British called them chiefs as they were deemed subjects to the British crown, thereby rendered unequal.[7] After the conquest, substantial social disruption, domination, and reorganization by the German and British colonial administrations, the Chagga states were officially abolished in 1963 by the Nyerere administration during its third year as the newly independent nation of Tanganyika.[8]

Etymology[edit]

The word Chagga an exonym, does not refer to the mountain; rather, it refers to the area around Kilimanjaro and the slopes where people live. The term's origin is unknown to linguists, but some theorize that it may have been the term used by speakers of Bantu languages (which includes Swahili) to describe the mountain's inhabitants. This theory would fit with the term's appearance in the early nineteenth century after the arrival of coastal caravan traders. Swahili is probably used similarly to the endonym, Wakirima "People of the Mountain" in Kichagga, to refer to the mountain and its inhabitants, but not to suggest any kind of social or political cohesion. But the word Chagga has no meaning among the people of the mountain.[9]

The word was taken by European explorers who arrived on the mountain in the middle to end of the nineteenth century from their Swahili guides. A pioneer in this was Johannes Rebmann. He referred to both individuals as "Jagga" in his letters and journal entries. While mentioning the various kingdoms, he thought of the mountain as one social and cultural realm. He was followed by explorers like Karl Klaus von der Decken who visited in 1869, Charles New in 1871, Harry Johnston in 1886–7, Hans Meyer in1187, and William Abbott in 1888, and they all came to refer to the mountain as Kilimanjaro and the locals as Chagga.[10]

The mountain was already referred to by the Swahili as "Kilima Ndsharo" (or "Dscharo"), "The Country of Dschagga," at the coast in the early 19th century. Rebmann said the mountains meaning from Swhaili is "Great Mountain" or "the Mountain of the Caravans" in 1848–1849, referring to the mountain that could be seen from a great distance and acted as a signpost for travelers. He and Krapf discovered that different adjacent peoples had different names for it: the Taita just reduced the coastal Swahili name to "Ndscharo." The Kamba termed it "Kima ja Jeu," or "Mountain of Whiteness." The Maasai dubbed it "Ol Donyo Eibor," or "White Mountain." It was simply referred to as "Kibo" by the Chagga themselves, particularly the Kilema and Machame. By 1860, Rebmann's German spelling of Kilimandscharo from 1848 to 1849 had adopted the anglicized name "Kilimanjaro".[11]

The most striking illustration came from Johnston, who built a homestead on the slopes of the mountain and spent close to six months there. He described the kingdom in which he lived, Moshi, as one of many "Chagga states" on the mountain in his texts. He speaks to the mountain as if they are a single group, destined in the natural order of events to become politically unified, despite the division and animosity existing on the mountain.[12]

The usage of a single name to describe Kilimanjaro sounded reasonable from a distance. The people spoke what was thought to be a dialect of the same language, lived on the same mountain slopes, engaged in the same types of agriculture, and shared many other cultural practices, spiritual beliefs, and social structures. Nevertheless, it also revealed a basic misunderstanding of Africa, based on the presumption that individuals could and ought to be divided into tribes, regardless of their individual histories and ideas about what constitutes diversity.[13]

This misconception quickly turned into the foundation of colonial rule. German expeditionary forces took over military command of the Kilimanjaro kingdoms in 1892, incorporating them into German East Africa. German control in the region drastically changed regional government in the years that followed. At the newly established town of Moshi, mangis were appointed local administrators who were tasked with keeping the peace, allocating land, organizing corvée labor, and collecting taxes under the supervision of a government official. Their prosperity now came from extorting money and labor from their subjects rather than through trade or combat.[14]

Moreover, the Germans started to combine many of the lesser kingdoms into bigger ones. By 1916, the total had dropped to 28 as a result. The mountain was significantly impacted by Christian missionaries as well. Following the Germans into Kilimanjaro in the middle of the 1890s, the Catholic Holy Fathers and the Leipzig Lutheran Mission soon spread across the mountain, erecting churches, schools, and clinics. Every chiefdom on the mountain had a resident European missionary by the year 1915. Kilimanjaro was approached by these officials and missionaries in the same manner as it was by the explorers—as one mountain, one community.[15]

For instance, Widenmann concluded that specific behaviors were distinctive to the "Chagga" people in his publications from the late nineteenth century concerning health on the mountain. The people were seen by missionaries as belonging to a single "tribe" that had only been divided by a century of inter-chiefdom conflict. Bruno Gutmann, a Leipzig missionary, provides one of the most extreme instances of this alleged oneness. Between 1907 and 1950, he wrote more than thirty books and essays about the inhabitants of the mountain. Along with acknowledging that they were all members of one tribe and shared an identity, he also recorded what he believed to be their shared cultural norms and rules.[16]

Geographic context[edit]

On the slope of Mount Kilimanjaro, which rises 5,895 meters above sea level, were the Chagga kingdoms and states. Without any prior foothills, the mountain rises directly from the plain. The Shira plateau, which blends into the main shape, was created by one volcanic spout; the jagged spur Mawenzi, by another; and the summit Kibo, which is the highest point in all of Africa, by the third and final enormous eruption, which forced its way between the two.[17]

Despite being only 3 degrees south of the equator, Kibo is a natural wonder since it is permanently covered in snow and ice. The Chagga gave their mountain the name "Kibo," which in some areas of Chaggaland means "Speckled" and in others is pronounced with a remarkable felicity as "Kiboo!" [18]

This having a mountain as focus, a precise position, in a single grate mountain which is one of the great spots of naturally fertile earth in the world, has bred the Chagga sense of identity. The sum of the individualistic histories of each tiny, long-established portion of the mountain rooted in that location, which itself drew its own identity from a mountain stream, ravine, spur of the hill, or a wall of the impenetrable forest; has colored their history, which is detailed and complex. Kahe and Arusha Chini are a part of the plain that is a component of the Chagga realm.[19]

According to Johannes Rebmann's journals and correspondence with Johann Krapf and the Church Missionary Society, people called themselves "mountain people or "Wakirima,"and those who lived elsewhere were known as "Wanyika" or "people of the plains." Moritz Merker also made note of the classification word "wandu wa mndeni," which translates to "people of the banana groves." They used this to contrast themselves with the Humba and Kuavi, which are pastoralists, and the Kasi, or hunter-gatherers. They show how the Chagga's conception of themselves and other people was shaped by the landscape. The importance of the mountain next to the lowlands is suggested by the terms Wakirima and Wanyika.[20]

In contrast to those who lived in the semiarid steppe, as the Maasai, those who lived on the mountain regarded themselves to be the benefactors of divine favor because they lived in a lush, well-watered environment. Meanwhile, Wandu wa Mdneny, Wasi, Humba, and Kuavi emphasize the value of sustenance. The mountain's main crop, bananas were also the defining element of the kihamba and daily life. They suggested a particular kind of social and political structure, which was viewed as lacking among the inhabitants of the plains.[21]

Kilimanjaro has served as a signpost from which other distant tribes, trading caravans, and travelers can get their bearings in addition to providing the Chagga with a focal point. The great snow dome can be seen high in the sky for up to 240 kilometers in all directions: to the east, just inland from the Swahili coral stone coastal cities of the Indian Ocean; to the west, deep in the Serengeti plains leading through to Lake Victoria; to the south, from the Great Rift Valley on the way to Unyamwezi and Lake Tanganyika; and to the north, across an endless plain, from Mount Kenya.[22]

The Chagga's northern neighbors are the Kamba, who are thinly spread throughout the arid region and have only one visible point, the Kamba hills; the Taita live to the east in the Taita Hills, which are visible from Chaggaland. The Taveta are situated next to them on the Lumi River's banks, down a plain that is concealed by a small area of forest. The Pare people reside to the south, concealed by the Pare Mountains' naked shoulder. The Maasai, who just recently migrated to the region from Kenya in the late 18th century, are to the south and west.[23] Located on the slopes of Mount Meru, to the northwest, are the Meru and the Arusha.[24]

Recorded history[edit]

Kilimanjaro is first mentioned in the Geography of Ptolemy, which was written in the second century AD. Ptolemy mentions a "huge snow mountain" that is located inland from the coastal city of Rhapta. Rhapta's location is still a mystery; it may have been in the Rufiji delta or to the north of the Pangani River's mouth, although Kilimanjaro is certainly in the background. The second-oldest surviving account of the East African coast and the ancient cities that grew along it from Mogadishu to Kilwa, on the Indian Ocean Trade, is found in Ptolemy's Geography. The Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, the first reference, dates from AD 90. Residents of coastal cities, especially those along the line from Malindi to Pangani, from whose hinterland the mountain was most easily visible, must have known this.[25]

A white mountain was mentioned by Arab geographer Abu'l Fida in the 13th century. Although no early Portuguese records of it have been discovered, it seems improbable that the Portuguese were unaware of it when they occupied the Swahili coast in the 16th century. Yet Martín Fernández de Enciso, a contemporary Spanish author, claims in his Suma de Geographia, which was published in 1519, that "west (of Mombasa) stands the Ethiopian Mount Olympus, which is exceedingly high, and beyond it are the Mountains of the Moon, in which are the headwaters of the Nile." It has been assumed that Kilimanjaro is meant by this.[26]

Kilimanjaro can be seen on top of Yombo hill just inland from the coast or eastward and seen across the Indian Ocean, the island of Zanzibar on a clear day. On early maps of the East African coast, the great mountain lying in the interior was set down. The world inside the mountain area was recorded much later, one fragment of knowledge being gradually added to another in the 19th century. Certainly, the Swahili knew about it for centuries, when Rebmann's colleague, Krapf, landed at Takaungu in 1844 there was plenty of information available concerning the great mountain which lay on the way to the inland sea of the great central lakes.[27]

The first recorded account we have is of the Swahili caravan leader Bwana Kheri, thanks to Rebmann writing it down. Kheri was a friend of the governor of Mombasa, who in 1848 commended him to Rebmann. It happened that Kheri was on the point of making one of his periodic journeys to Kilimanjaro with his caravan, and Rebmann joined him. He visited Kilema making Kilema the first kingdom visited by a European. Machame and Kilema were visited on the second and third visits by Rebmann.[28]

Von der Decken traveled to the mountain twice in 1861. In 1861, he visited Kilema and Machame, traveling from Mombasa via Taita and Taveta, following a course parallel to the Pnagani River, passing through the southern part of the Usambaras and arriving at his chosen port of Wanga. In 1862, he visited Uru and Moshi, traveling from Wanga via Usambara, Ugweno in north Pare, Lake Jipe through Ndara and Buru mountains to Mombasa.[29]

In 1871 an English Methodist missionary, Charles New, Journeyed to Kilimanjaro when he visit the kingdoms of Marangu, Mamba, and Msae; going from, and returning to, Mombasa he took the route through Taita and Taveta. To the Chagga, the European explorers were unusual visitors since they didn't come to trade anything. Rebmann intended to spread the word of the Christian God among the heathen, and von der Decken and Charles New planned to climb the mountain. They were all seen as magicians with their instruments and Holy Book. The three travelers, separated from each other by ten-year intervals, left written accounts for which Chagga's life can be seen this time in the 19th century. They allowed for dating of the rule of certain mangis and even handed down by oral tradition.[30]

Sir Harry Johnston and Hnas Meyer also visited Moshi in the 1880s and wrote reports of the place. The German Roman Catholic Fathers of the Holy Ghost established their station in Kilema in 1892, the same year that the English Church Missionary Society (CMS) withdrew from Kilimanjaro and was replaced by the German Lutheran Mission operating out of Leipzig. The first station was established by the CMS in Moshi in 1885.[31]

The German government entered the picture last but not least. Mangi Rindi of Moshi signed a piece of paper given to him by von Juhlke, an emissary of the German government, in 1885, and the church's influence helped make Kilimanjaro German territory the following year when Britain and Germany signed a treaty outlining the borders of German and British East Africa.[32]

The Chagga states[edit]

The mountain was divided into kingdoms, which the British authority ultimately degraded to chiefdoms and which, by 1886, were governed by sovereign independent mangis (kings in Kichagga). After that, Kilimanjaro was included in the governing structure, and the "chiefs" authority was constrained accordingly. From 1886 to 1916, Kilimanjaro was governed by the Germans as part of German East Africa. From 1916 to 1961, it was governed by the British as a part of the territory that had been renamed Tanganyika. In December 1961, it was incorporated into the independent sovereign state of Tanganyika.[33]

As of 1899, there were 37 Kingdoms atop the mountain, according to August Windenmann, a German surgeon stationed at Moshi in the 1890s[34]

|

|

|

Except for Kahe and Arusha Chini, all other states are located on the mountain. Kahe and Arusha Chini are primarily connected to Chagga for administrative reasons. Although there is an old connection between them in the ancient trade route from Pangani that the coast passed through Masinde and then through Kahe and Arusha Chini, themselves near the banks of the Pangani River before it reached the mountain, their different histories, as told by their elders today, highlight a contrast to that of the Chagga. Today's Chagga will only acknowledge the Kahe people as being Chagga, but they will consider the Arusha Chini people to be distinct from themselves.[35]

From Kibongoto (Siha) on the west to Usseri on the east, all of the kingdoms descend in erratically vertical sections, up to the forest line, down to the plain; some are better off for the plain than others, but only Mamba is barred from the plain. Natural landmarks, primarily ravines, form the borders of the kingdoms. The land holdings of the kingdoms, mitaa, or clans have not been measured. However, some, especially Kibosho, Machame, Masama, and Kibongoto, are larger than others (Siha). States like Kilema and Kirua, in comparison, are more condensed and compact.[36]

Chaggaland's area and people are divided in half between Sanya in the west and Moshi in the east. As you move east toward Tarakea, the terrain becomes dryer and less fruitful because it receives less rainfall and better water from streams fed by glaciers. Rombo's rivers, except for the Lumi River, are dry throughout the dry season; there are few furrows, therefore the kingdom depends on the rains, specifically the brief rains in December and the long rains lasting from mid-March to mid-June. Yet, Rombo is just the least fruitful region in comparison to Chaggaland's extremely high standards. By any other standard, the area is very fruitful due to its large trees, dense vegetation, and broad wide meadows of plumed waving grasses.[37]

Defence[edit]

The Chagga were at the vanguard of tactical and weaponry advancements for the majority of the 19th century, undoubtedly aided by their proximity to both the Maasai and the Arabs. Traditional reports of the warfare between the Maasai and the Rombo clan of the Ngasseni undoubtedly give a decent indication of how the rest of the Chaga fought at the beginning of the century. Rombo was the region most open to attacks from the steppe to the north. The Ngasseni, whose battle cry is Wuui! Wuui! Otiemagati! would ambush the enemy in the woods and banana groves, set up in three lines: spearmen in front, shield-carrying men behind them, and archers in the back. [38] Throughout the century, the traditionalist Rombo continued to employ these strategies, while elsewhere in Chagga, Maasai influence grew significantly beginning in the 1860s. It is known that at least two chiefs, Orio of Kilema and Mdusio of Siha, resided with the Maasai at this time and studied their combat techniques.[39]

Sina of Kibosho, who seems to have been a remarkable innovator, was the other significant impact on tactics. He kept his warriors under severe discipline and housed and trained them in his stone palace; it was rumored that the punishment for sleeping at home was death. The broad-bladed Maasai spear is thought to have been given to Kibosho by him, and he is also credited with designing his own throwing spear with a narrow blade "as long as the human arm." He kept all of their weapons in his arsenal and only released them when necessary.[40]

His troops typically launched their assaults at dawn, with the advance guard initially dispersing and setting a few sparsely placed huts on fire to mislead the adversary about the direction in which the main body was moving. They then advanced in three waves, with men with stabbing spears in reserve in the back and men wielding throwing spears in front, accompanied by a line of musketeers.[41]

Chagga first encountered firearms in the 1860s. Through his connections with the Arabs, Mandara of Moshi was the first Mangi to obtain them, and he used them naturally to gain an advantage over his competitors. By the 1880s, Swahili dealers had begun purchasing Snider rifles from soldiers returned from European missions and selling them in Chagga, where the new bunduki snap design was obviously preferred to the traditional bunduki za fataki or muzzle-loader.[42]

400 warriors of Mangi Marealle of Marangu were equipped with Snider rifles in 1884. Even though he already had a few tiny cannons to protect his stockade, Mandara asked Johnston to show his smiths how to make more of them. Despite this, Johnston was sure that the spearmen continued to cause the vast majority of losses in Chagga combat since so few men had any understanding how to shoot their firearms correctly.[43]

Communication among the states[edit]

Across all the mountain runs an intricate network of tracks. In modern times broad dirt roads have been made leading from Moshi town up to the center of each kingdom and on the mountain itself, notably, the horizontal road linking Usseri to Moshi. For the most part, these tracks go back to the olden days. Many in the first place were probably made by elephants, finding the easiest ways through the forest and down and across the steep ravines. By innumerable paths, still known today, the Chagga of old communicated with each other, going not only from one kingdom to the next but from one far-flung kingdom to another and down into the world outside the mountain.[44] There are other Kichagga dialects, some of which are unintelligible, in Siha and the eastern region of Usseri where people speak Kingassa, a different tongue. Taita and Kichagga are related.

The history of the Chagga is shaped by three main horizontal routes that pass through various altitudes: the lower track traverses the plain, the middle track travels through Chaggaland's most populous region, and the upper track passes through the high forest or even above it via the high open savanna. When communicating with one another, the ancient Chagga had to decide strategically between these three sources of power and whether their kingdom had friendly or hostile relations with the states they had to pass through. Generally speaking, the intermediate track was the most practical and efficient since it spanned the ravines where they were less steep than either above or below.[45]

For safety reasons, people frequently took the upper and lower tracks to avoid unfavorable situations. Yet, there are times when the upper track is the most practical and direct option. For instance, the route from Marangu to Mkuu passes through a high forest, and the upper routes were particularly popular between the countries of Rombo and Vunjo. The discovery of an upper track that circumnavigated Kilimanjaro and reached Siha on the far west is one of the most intriguing pieces of evidence gleaned from a study of these ancient trails. This upper track ran from the Kingdom of Usseri, the furthest eastern boundary of then-inhabited Chaggaland.[46]

Infrastructure[edit]

The other network running across the mountain is that indigenous marvel, the Chagga irrigation system using furrows (Mfongo in Kichaga). Each furrow is cut from an intake high up on a mountain stream whence it is led by a circuitous course for miles following the contours of the land. From each main furrow branches and sub-branches are led off until one gets down to the unit of the modest channel of clear flowing water which runs through every homestead, providing the Chagga with water for drinking, washing, and cultivating his land.[47][48]

Furrow surveyors used little sticks as their only tool to draw the required course in the furrows and cut them. Their biggest talent was used in the initial phase when determining where to make the intake and how to organize the course of action. In some places today, for instance across the hillside of the boundary at Kilema, a series of up to five main furrows run one above the other, appearing to defy gravity and to be running back to the river rather than down towards the plain.[49] This is because their plotting was so exact that it prevented future landslides. In the kingdom of Mbokomu, there was a special art associated with surveying, particularly a method by which furrows were carried right over the oddly precipitous ravines using hollowed tree trunks arranged horizontally and resting one on top of the other.[50]

Plotted within the kingdoms, each furrow has a name and historical significance, ranging from the earliest, which are less in length and are located higher up the mountain, to the lengthy, magnificent constructions of the 19th century. Mangi Mlatie of Mbokomu, a former king, was one of the illustrious surveyors. No mangi is more joyfully remembered because Mlatie, who was temporarily exiled, surveyed furrows throughout the highlands wherever he happened to be. These furrows still hold his name and are still used by the Chagga today.[51]

Homestead[edit]

Even in the most populated areas of Chaggaland, every single family resides in the privacy of their farmhouse, which is fenced in called kihamba in Kichagga. The ancient Chagga sacred plant of peace and forgiveness, Masale Dracaena, surrounds each dwelling. A banana grove can be found within, its long, overhanging fronds shading tomatoes, onions, and always different types of yam. A house in the shape of a spherical beehive, built of mud and thatched with grass or banana leaves, stands in the center of the grove. The sleeping quarters, which can be either a hide or a bed, are located close to the door and have a space for the husband's hoe and other tools. A fire burns in the center of the room, supported by three stones, and a little loft holds bananas for drying above the fire.[52][53]

Outside, beehives made of hollowed-out tree trunk lengths with stoppers are hung from the trees; hides are stretched on pegs to dry at the door; in some homesteads, a blacksmith may be seen hunched over hot embers with his anvil and goatskin bellows; in others, a woman shaping and firing earthen pots is more rarely seen.[54]

Neighbors usually belong to the same clan. Within the area covered by that clan interior connecting paths run between one homestead and another, and the whole area is demarcated by a bigger hedge or an earth bank from the adjacent dwellings of the next clan. Several clans comprise a mtaa, and several mtaa in turn a kingdom. When Rebmann reached Kilema in 1848 he immediately remarked upon the orderliness which prevailed thanks to the strong authority exercised by the mangi. He was captivated by the well-being and talents of the people, by the good climate and the beauty of the land.[55]

Chagga states in the 20th century[edit]

Following the First World War, Kilimanjaro underwent a further set of political and economic upheavals as British rule began. Similar to the Germans, the British also accepted the idea of "one mountain, one people," and they took several actions to turn cultural "reality" into political reality. The mangis were combined into a single organizational structure known as the Chagga Native Authority in 1919, and they were made into salaried workers by the district headquarters in Moshi town. These actions aimed to strengthen the authority and lessen corruption. The agency also established three regional Chagga councils, each of which was made up of the mangis for that region as well as their separate treasuries.[56]

The emergence of coffee was the most important economic development throughout the British era. As early as 1900, Catholic missionaries brought Arabica coffee to the mountain. Nonetheless, coffee production increased during the 1920s, partly as a result of Charles Dundas' activities. When he was appointed as the Moshi district officer in 1920, he thought that coffee was "the sine qua non" of the growth of the indigenous economy and started to provide mountain farmers with direct government assistance in growing the commodity. The outcomes were extraordinary, to put it mildly. The Dar es Salaam government began to view the Kilimanjaro people as economically progressive in the 1930s.[57]

The extraordinary success of African coffee farming thrilled the government and brought great income to Chagga farmers, but it also intimidated the European settlers in the area, the majority of whom were also actively engaged in coffee cultivation. In the 1920s, settlers turned into aggressive opponents of African coffee production. They worried that a booming African coffee market would not only drive down prices but would also make it harder for them to acquire the low-cost agricultural labor they needed to manage their estates. The Kilimanjaro Planters Association (KPA), an organization that actively pressured the government to outlaw all African coffee cultivation on Kilimanjaro as had been done in Kenya, was founded in 1923 by a group of settlers.[58]

By the 1930s disputes over land, water, and coffee farming did not develop in a vacuum; rather, they occurred in the context of a society that was changing quickly, one that was characterized by an increase in educational opportunities and Christian conversions. People first turned to their mangis when they wanted to voice their complaints. But, the mangis had taken on a dangerous stance. Although they were paid agents of colonial power, they pretended to represent the interests of their people. A new generation of educated elites, coffee growers, and clan headmen were the other three significant power players on the mountain that they had managed to alienate.[59]

Kilimanjaro had nonetheless become a vital component of the colonial economy, but there was still a crippling lack of cohesion. For instance, the residents of the mountain still refused to identify as Chagga. "If a Chagga, preparing to give evidence in Court, is questioned about his tribe, he generally says, "Mkibosho" or "Mkilema" or whatever the name by which the people in his particular area are called: if he adds, "Mchagga," it is an afterthought,".[60]

The registration requirement played a role in public outrage, which was significant, yet the majority of people opposed dissolving the KNPA. People were willing to resist the mangis to save the group since it had evolved into a type of uniting point against both them and the settlers. The organization continued to exist, indicating that people on the mountain were now identifying politically with an organization that transcended kingdom lines. For a few more years, the KNPA remained a formidable force on Mount Kilimanjaro, but an accounting scandal in 1932 eventually led to its dissolution.[61] By this time, the government had firmly committed to promoting African coffee growing, which was now very profitable, but it also wished to purge the organ of its "radical" components. The scandal allowed the district office to remove the organization's current leadership, disband it, and replace it with the Kilimanjaro Cooperative Union (KNCU). Compared to its predecessor, the new co-op was less of a political forum, but it still operated independently of the mangis. Both KNPA and KNCU were successful in organizing people to defend their rights in coffee cultivation. People formed these organizations to defend themselves against foreigners beyond the mountain and their mangis, not from one another.[62]

The decline of the Chagga states[edit]

Clans used their connections with other clans as a source of resources to give the traders the food, water, ivory, and slaves they needed. Throughout time, the mangis in these alliances evolved as the main clan members. They were the male age groups responsible for organizing attacks on neighboring ridges to dominate trade and acquire slaves, as well as for defending against such incursions. They not only acted as trade negotiators on behalf of the clans. By 1890, the mountain's key political personalities and the monarchy as a significant political entity had emerged.[63]

Though still the permanent units of authority on the mountain, the so-called "chiefdoms" underwent several modifications in the middle of the 20th century. They were formally divided into three divisions, each under the supervision of a divisional chief, from 1946 to 1961. From 1952 to 1960, the superstructure of the three divisional chiefs was expanded by the addition of a single supreme Paramount Chief. In 1960, the Paramount chief was replaced by the President, and in 1961 the divisions and the position of the divisional chief were abolished. The council's advice to the chiefs was developed at the same time. The 1932-founded Chagga Council made strides in 1952 and again in 1960. It gave a new democratic elected element a foothold that, starting in 1952, slowly started to undermine the hereditary main rulers' power.[64]

Chiefdoms as of 1961, west to East:

| Chiefdoms | Mangi | Division Group |

|---|---|---|

| Kibongoto (Siha) | John Gideon | Hai |

| Masama | Charles Shangali | Hai |

| Machame | Gilead Shangali | Hai |

| Kibosho | Alex Ngulisho | Hai |

| Uru | Sabhas Kasarike | Hai |

| Moshi | Tom Salema | Hai |

| Kirua | Balthasar Mashingia | Vunjo |

| Kilema | Aloisi Kirita | Vunjo |

| Marangu | Augustine Marealle | Vunjo |

| Mamba | Samuel Werya | Vunjo |

| Mwika | Abdiel Solomon | Vunjo |

| Arusha Chini | Wilson Ndiliai | Vunjo |

| Kahe | Joas Maya | Vunjo |

| Keni Mriti Mengwe | Wingia Ngache | Rombo |

| Mkuu | George Selengya | Rombo |

| Mashati | Edward Latemba | Rombo |

| Usseri | Alfred Salakana | Rombo |

The new divisional leaders were addressed by the existing Chagga Council. Despite allowing for some popular rule by the people, these reforms concentrated power in the hands of the divisional chiefs and strengthened the clan chiefs' dominance. Most significantly, they gave the divisional chiefs little to no checks on their authority and gave them control over land allocation. Beginning in 1945, a group of worried coffee farmers known as the Chagga Association was formed under the leadership of previous activists Merinyo and Njau. This organization developed an interest in issues of governance as well as the preservation of the general public's rights to land and water.[66]

Merinyo and Njau argued for the appointment of a paramount chief to lead the current mangis. They believed that doing so would weaken the influence of the local rulers and increase local democracy and fairness in matters relating to land and water. The Chagga Association's adoption of the name by the mangis is possibly its most significant aspect. The term "traditional" authority" refers to colonial governance in a political context. Yet, this new group repurposed the phrase to refer to the unification of the populace as a whole in opposition to the mangis’ tyrannical exercise of power.[67]

The divisional mangis received several hundred acres of excellent former German farmland from the government in 1947. The lands remained in their possession and were never transferred, just as the Chagga Association had prophesied. Merinyo and Njau established the Kilimanjaro Chagga Citizens Union as a new political organization in response to the lack of advancement (KCCU). Its two objectives were to change how the land was distributed and to create a more unified government by electing a mangi mkuu (Paramount Chief). The politically disaffected populace, including "dispossessed chiefs, ambitious traders and farmers, elderly KNPA militants, underprivileged Muslims, noblemen who despised mangi authority, and young educated men restless with the old system, were highly popular with the organization. In 1951, it expanded rapidly to 12,000 members.[68]

The colonial administration had serious concerns about the KCCU because it thought that local indirect rule implementation might be threatened by this widespread opposition to colonial policy. Yet, it was united in its aim to establish central authority on the mountain to improve governance and cut expenditures. To adopt a paramount chieftaincy and even allow the mangi mkuu to be chosen by popular vote, the administration reached an agreement with the Chagga Council and the KCCU in 1951.[69]

Three of the four candidates for the 8 October 1951 election were the divisional chiefs who were still in office: Petro Itosi Marealle of Vunjo, Abdiel Shangali of Hai, and John Maruma of Rombo. Thomas Marealle, the fourth, was somewhat of an outsider. He shared the same main clan as the other candidates, which was a prerequisite for running in the election. He was Petro Marealle's nephew, another candidate. However, Thomas Marealle had not been actively involved in local politics his entire life, in contrast to his rivals. He finished his secondary education on the mountain and then went on to study overseas at Trinity College, Cambridge, and the London School of Economics. Marealle distinguished himself from the divisional leaders by campaigning on behalf of the mountain's inhabitants rather than a specific chiefdom or division.[70]

Marealle ultimately prevailed, gaining every chiefdom but one. His triumph was a significant turning point in Kilimanjaro's history. He not only served as Kilimanjaro's first paramount chief, but he also did it with widespread backing from the chiefdoms. Marealle was attractive for a variety of reasons, including his personality, his position as an outsider, and his advanced education. Yet, his victory was primarily a result of their battle for control of the mountain's resources and their conviction that he would be best able to represent their interests.[71]

On January 17, 1952, Thomas Marealle became the paramount chief of Kilimanjaro. Governor Twining presided over the installation ceremony, which combined 'traditional' and modern rites and customs. Marealle utilized tax money from the booming coffee industry to engage with local authorities on important concerns for the following several years, such as water supply, road development, school, and dispensary construction. Regarding the matter of significant concern, he had little actual power.[72]

The emerging sense of Chagga identity, which Marealle attempted to exploit, is best recognized during his time serving as paramount chief. He also took part in developing fresh cultural imagery. He ordered the creation of a Chagga flag in 1952. The background is anchored by the mountain's flag-like, snow-covered top. a banana tree on the right, a coffee tree on the left, and a masale plant connecting the two are the three photos in the foreground. The mountain's symbol of tradition and heritage is the banana tree, while the coffee plant symbolizes the mountain's present and future wealth. The masale, a traditional peace symbol on the mountain, connects the past and present in this way. The leopard, a symbol of strength, finally envelops the entire landscape.[73]

Marealle pushed the idea that Chagga identity and political unification had to emerge over time, drawing on the colonial idea of "one mountain, one people." He refers to the 1951 election as "the historic come together of the whole tribe" in the introduction he penned for the Chagga Day 1955 booklet. Then he made extensive reference to Charles Dundas' works, who claimed in 1924 that a unique Chagga kingdom would have risen over time had a colonial rule not been interrupted. Marealle saw Chagga Day as a delayed realization of what Dundas and others had said—namely, that the peoples of Kilimanjaro were destined to unite as one.[74]

He had some regional development triumphs, but did not deal with the main problem that helped him win the election: the land question. As a result, he lost the support of the clan leader coffee growers, who believed he had failed to bring about the necessary reforms to amend the policies governing land distribution (such as eliminating the system of divisional chiefs). In addition, he alienated educated youth who questioned his commitment to land reform as well as his preference for using archaic symbols and dictatorial political methods over more democratic ones. Marealle disagreed with the nationalist because of his political beliefs. One of the last areas in the colony to support the independence movement was Kilimanjaro.[75]

The TANU leadership, especially Julius Nyerere, a former friend of Marealle, believed that the overt displays of identification on the mountain erred on the side of ethnic nationalism and were detrimental to their mission. The pressure mounted, and Marealle resigned in 1958. A second political reform referendum was held two years later, this time replacing the supreme chieftaincy with an elected president. As colonial control came to an end, primarily leadership in mountain politics underwent a significant shift in the year 1960. Almost immediately after Marealle's resignation as mangi Mkuu, the Chagga Day celebrations and the practically patriotic markers of Chagga identity that had arisen vanished.[76]

Throughout the ensuing years, as the independent state of Tanzania took shape, a common Tanzanian identity started to emerge. Despite this, the sense of Chagga identity created by political conflict and competition for resources has persisted, particularly when residents of Kilimanjaro have moved to other regions of the nation. Today, it connotes a sense of belonging to the mountainous scenery as well as cultural and political legacy.[77]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 22. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ von Clemm, Michael. “12. Trade-Bead Economics in Nineteenth-Century Chaggaland.” Man, vol. 63, 1963, pp. 13–14. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2797613. Accessed 10 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Yonge, Brian. "The rise and fall of the Chagga empire." Kenya Past and Present 11.1 (1979): 43-48.

- ^ Vansina, Jan. “Once upon a Time: Oral Traditions as History in Africa.” Daedalus, vol. 100, no. 2, 1971, pp. 442–68. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20024011. Accessed 10 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Iliffe, John (1979). A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780511584114.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ "Chagga people- history, religion, culture and more". United Republic of Tanzania. 2021. Retrieved 2023-04-08.

- ^ Chiefs (Abolition of Office: Consequential Provisions) Act of 1963 53 (PDF). Republic of Tanganyika. 6 December 1963.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 38. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ “The Kilimanjaro Expedition.” Science, vol. 5, no. 107, 1885, pp. 152–54. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1760887. Accessed 10 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 19. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 20. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 21. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ "Hanby, Jeannette & Bygott, David: Ngorongoro Conservation Area". ntz.info. Retrieved 2023-01-01.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 21. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 22. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 22. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 22. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 22. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 36. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 36. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 37. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 37. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 22. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 22. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 24. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 25. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Heath, Ian (2004). East Africa: Tribal and Imperial Armies in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar, 1800 to 1900. Foundry. p. 137. ISBN 9781901543353.

- ^ Heath, Ian (2004). East Africa: Tribal and Imperial Armies in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar, 1800 to 1900. Foundry. p. 137. ISBN 9781901543353.

- ^ Heath, Ian (2004). East Africa: Tribal and Imperial Armies in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar, 1800 to 1900. Foundry. p. 137. ISBN 9781901543353.

- ^ Heath, Ian (2004). East Africa: Tribal and Imperial Armies in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar, 1800 to 1900. Foundry. p. 137. ISBN 9781901543353.

- ^ Heath, Ian (2004). East Africa: Tribal and Imperial Armies in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar, 1800 to 1900. Foundry. p. 137. ISBN 9781901543353.

- ^ Heath, Ian (2004). East Africa: Tribal and Imperial Armies in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar, 1800 to 1900. Foundry. p. 137. ISBN 9781901543353.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 24. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 25. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 25. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Grove, Alison. “Water Use by the Chagga on Kilimanjaro.” African Affairs, vol. 92, no. 368, 1993, pp. 431–48. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/723292. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 25. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Tagseth, Mattias. “The Expansion of Traditional Irrigation in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol. 41, no. 3, 2008, pp. 461–90. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40282528. Accessed 10 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 26. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 25. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 27. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Cleveland, David A., and Daniela Soleri. “Household Gardens as a Development Strategy.” Human Organization, vol. 46, no. 3, 1987, pp. 259–70. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44126174. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 27. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 27. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 22. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. p. 23. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Bender, Matthew V. “BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO.” The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.