Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2007 December 20

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < December 19 | << Nov | December | Jan >> | December 21 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

December 20[edit]

Mail delivery[edit]

My mail box has a holder on the bottom for second, third, bulk mail and unaddressed flyers but the postmen never use it. Instead they cram the regular first class mail along with the second, third, bulk mail and unaddressed flyers right into the mailbox. This forces me to go through the junk mail to be sure I do not throw first class away. Is this a conspiracy on the part of the post office and the advertisers who pay them for such method of delivery or can I somehow force them to use my mail box for only first class delivery? 71.100.14.54 (talk) 00:03, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- I don't think the Science desk is appropriate for your question. Anyway, the answer is this: People aren't going to take on extra work for free, just because you'd like them to. -- Coneslayer (talk) 00:16, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- ..ah a response from a postal employeee. Just what I expected. 71.100.14.54 (talk) 00:17, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Coneslayer, you really have some impressive credentials for a postal employee. Someguy1221 (talk) 00:21, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- I just do it for the benefits. Got any Advil? My back always hurts this time of year. -- Coneslayer (talk) 00:23, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- A quick note: your question poses a false dichotomy -- that is, you may be unable to force the postal service to use various mail slots in the fashion you prefer without supposing a shadowy bulk advertising cabal. Similarly, the occasional delivery of folded do-not-fold envelopes does not provide strong evidence for the postal service being repurposed by Martian Nazis. Godwin's Law! I win! That said, I think Coneslayer is right -- it's unlikely you'll find a solution without payment involved somewhere (if then). — Lomn 00:39, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- It's not a scaleable idea anyway. What makes more sense: everyone sorts their own mail (taking, say, 1 minute per day), or the postal employees sort everyone's mail (1 minute per day * everyone who they deliver to). And what are you going to do if the postal guy gets it wrong and puts an important-but-junky-looking-envelope (like the sort that new ATM cards come in, to avoid being stolen) into the junk slot, and you throw it out? How would you feel then? Better to just take that minute and not worry about it too much. Or see about getting your name removed from the junk lists to begin with (e.g. [1]), or call your congressperson and tell them you're in favor of tougher junk mail laws. --24.147.86.187 (talk) 02:05, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

Interesting... Normally I would think that of all people who might see the value in and respect and support the existing mail classification system (First class, etc.) it would be mailmen. Okay, so I can accept the fact that they are lazy. That said, it now does not make sense why they would go to all the trouble of unsorting the bulk and class mail when they are the ones who grab a piece of junk mail from a box of identical pieces and combine it with class mail to begin with. 71.100.14.54 (talk) 02:24, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- You are bordering on trollish behavior. It was explained repeatedly that it is not a matter of being "lazy" as you claim. It is a matter of time. It takes longer to sort at the box. If every box took longer, it would require more people to deliver the mail in the same amount of time. That would cost more money. Where do you suggest the extra money comes from? -- kainaw™ 02:33, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Kainaw dude, did you not read above? Much of the junk mail does not have a name or address printed on it but is rather provided to the postman in a box from which he must grab a piece and do the work of unsorting it by combining it with class mail and other pieces which have addresses. Defending laziness is one thing but you in your defense are defending extra work for both the postman and the postal customer. 71.100.14.54 (talk) 02:46, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- It's still simpler and less effort that way, for at least two reasons I can think of off the top of my head. Note that these aren't necessarily the actual reasons, but they do seem to fit the evidence.

- Not every mailbox is like yours. Many are just a single box, where the postal worker has to put all the mail. In general, it is quicker and easier to have a single method to apply in all cases, even though tailoring the method will produce better quality results (for example, catering for 100 by making big batches of food versus cooking individual dishes). In this case, the only method that can be applied to all mailboxes is to stuff everything together.

- The postal worker has to pick up mail from two piles - the addressed stuff and the junk mail. Getting them both out together, holding them in the one hand, and putting them in the one mailbox is more efficient than getting one lot, putting it in its box, and then getting the other and putting it in its box, and less awkward than holding a pile of mail in each hand and trying to make sure that the right pile goes into the right box.

- On another note, wherever you may be (I would assume US?) can you get "No Unsolicited Mail" stickers to place on your mailbox? They're fairly common in Australia, and (in theory) mean that only mail that's addressed to you will be delivered. Confusing Manifestation(Say hi!) 03:05, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Actually a superior idea has come to mind. Every time I visit one of those hobby sites that specialize in building robots they are always looking at ways a robot can do the job of a human. Already we have robots for the home that are so sophisticated they can run around the house all day cleaning up spilled peanuts, etc. without getting in our way. The police already use robots and a form of robot is even used to deliver the mail in large government and corporate buildings and DARPA has paid out over a million dollars in prizes for university teams to build cars that can drive themselves. 71.100.14.54 (talk) 03:40, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- I did read what you wrote. You wrong to the point of carrying on an argument just for argument's sake. Which is faster; picking up two things and putting them in one box in one motion or picking up one thing and putting it in a box before picking up something else and putting it in another box? Obviously, the single motion is faster. Two motions is slower. Perhaps you suggest we should have three-armed postal workers. You are also completely ignoring the fact that the bulk mail people paid to have their mail put in your mailbox - not in a separate box. It is not the postal worker's option to stick the mail in a separate box. -- kainaw™ 03:35, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Well as a matter of fact you are wrong. Postmen used to place bulk mail in the bulk mail receptacle. As for three armed postal workers there are lots of jobs that can be done less perfectly as a matter of expedience. For instance, we could get rid of this hourly wage and overtime thing and just pay everyone the same salary. 71.100.14.54 (talk) 03:43, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- I never claimed that postmen never placed bulk mail in mail receptacles in the past. I stated that it takes longer to place mail in two receptacles than it takes to place it in one. I also stated that bulk mail postage is (present tense) a payment to place the mail in the person's mailbox, not in a separate box or trashcan - assuming we are discussing the postal laws and regulations in the United States. Once again, claiming a person has said something that they did not say just to further an argument is simple trolling. Continue complaining all you like. I seriously doubt anyone is willing to continue taking your bait. -- kainaw™ 03:47, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- On that note I will now conclude my discourse with you by stating that you are making a personal attack and that what separates the mail is not only the address but its classification. Of course with only one box a postman has not choice but by law with a box for each classification the postman is failing to properly deliver the mail if he does not place each class of mail in the right one. 71.100.14.54 (talk) 03:54, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- If that's true, it seems your question and/or complaint must certainly be with your local post office (for failing to obey this law), and not with anyone here. (Silly me, I assumed you were asking us why your postman doesn't do this, but if you already know that he's required to, well, get on it with those properly-directed complaints!) —Steve Summit (talk) 04:19, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- On that note I will now conclude my discourse with you by stating that you are making a personal attack and that what separates the mail is not only the address but its classification. Of course with only one box a postman has not choice but by law with a box for each classification the postman is failing to properly deliver the mail if he does not place each class of mail in the right one. 71.100.14.54 (talk) 03:54, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- I never claimed that postmen never placed bulk mail in mail receptacles in the past. I stated that it takes longer to place mail in two receptacles than it takes to place it in one. I also stated that bulk mail postage is (present tense) a payment to place the mail in the person's mailbox, not in a separate box or trashcan - assuming we are discussing the postal laws and regulations in the United States. Once again, claiming a person has said something that they did not say just to further an argument is simple trolling. Continue complaining all you like. I seriously doubt anyone is willing to continue taking your bait. -- kainaw™ 03:47, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

I haven't read through all the above, so apologies if I repeat anyone, but: two points:

- I don't know where you live, but in the U.S., for as long as I've been aware, all the mail comes in one box. If there's a second place for non-first-class mail, it's an antique, a forgotten relic. Having the postman sort and deliver my mail in two piles simply isn't part of the current contract.

- It's true that the postman has to do a certain amount of extra work to give everyone on the block one of those junky advertising circulars. I, too, wish that my postman didn't bother, so that I could be spared the time of sorting it back out from my real mail and throwing it away. But if my postman abided by my wishes and didn't deliver it to me (or delivered it to, say, a wastebasket I placed on my porch for the purpose), he would be, like it or not, violating his contract with the advertiser who paid to have that circular delivered to me. Supposedly, the profit margin for the post office is higher for bulk-rate junk mail than it is for first-class mail, so unfortunately, it really is in their best interest to keep taking money from the advertisers in return for shoveling the junk mail at us. —Steve Summit (talk) 03:51, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Their highest profit margin comes from the P.O. boxes you rent. 71.100.14.54 (talk) 03:59, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

Followup: Can I avoid mail-spam if I use a P.O box?[edit]

I've never had a PO box - but is it possible that I could simply take down my mailbox and get a PO box for my mail? I presume they don't send the inch thick grocery store junkmail to PO boxes - right? SteveBaker (talk) 14:22, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- I used to have one when I was in the Marines. They cram it all in there. By the time I got my mail out, it was a crumbled brick of paper that I had to untangle. I complained and discovered that the post office is more interested in delivering bulk mail (since they get paid for that) than not delivering it (since they don't get paid for that). Also, there's that nit-picky law thing that says they have to deliver mail that they are paid to deliver - even if the recipient doesn't want it. -- kainaw™ 14:36, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- I have a P.O. Box. Every piece of junk mail I get at home addressed to "Homeowner", I get a second copy of in my P.O. Box addressed to "Boxholder". So the P.O. box more or less doubles my junk mail. —Steve Summit (talk) 15:07, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Oh...crap. Another great idea bites the dust in favor of reality. Nevermindthen. SteveBaker (talk) 15:28, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- If it's worth $1 to you (far less than the cost of renting a PO box), then you can go here and opt out of most direct mail. I did this long ago when there was no online option and it required a postal letter to get on the opt-out list (but it was free), and it was effective for awhile. Then I moved away and moved back and never have gotten around to doing so again ... --LarryMac | Talk 19:09, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- I don't think that's going to work. That's for companies (like credit card companies) who mail the product directly to your address. I'm not particularly swamped with those. The thing that bothers me is about a 1" slab of newsprint and glossies that arrives every few days addressed to "General Delivery" or something. The $1 service you mention isn't going to stop that because the mail isn't addressed to me - it's just spam. The scale of this problem is insane. At my apartment complex here in Austin, TX, there are about 200 mailboxes in one big 'wall'. Every day, the apartment complex staff haul away FOUR trashcans full of unread mail. You can stand there and watch people pull the stuff out of their mailbox - flip through it really quickly to ensure that there is no 'real' mail in there - and dump it right into the nearby trashcans. 250 times one inch of paper is a pile 20 feet tall! It fills FOUR trashcans every few days! I've never - not even once - seen someone look at the stuff properly - let alone take it away with them. I can't imagine how the local supermarkets can justify the expense of designing, printing and paying the post office to distribute all of that crap if absolutely NOBODY reads it. It's crazy to watch the postal guy hauling out box after box of this stuff - putting it into all of the mailboxes - and then to see apartment residents taking it out again and dumping it in the trash without once looking at it. Aside from the insane waste of time and money - it's an environmental nightmare! However, we have no way to stop it. The post office (who could easily stop it by requiring it to be properly addressed to individuals and to have senders be required to honor the "do not spam me" list) don't want to stop it because that's the only thing that's keeping mail delivery running in the face of email...and the senders clearly find it cost-effective (although I have no clue how that could possibly be!). The victims here (me - and the environment) don't contribute to any part of the cash flow involved - so we're powerless to stop it. SteveBaker (talk) 20:48, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- You are assuming that "nobody" reads it. I did development for a grocery chain once - specifically for the department in charge of the circulars and coupons. They are all statistics geeks. They count up how many coupons are used. Each one has value as a person who read through the circular enough to clip out a coupon. Then, they compare that value to the cost of mailing the circular. The post office doesn't let you ignore apartments. They give you routes. For example, you can send it out to route 32. Everyone on route 32 will get it - regardless of what kind of home it is. Now, add to the coupons the shopper cards and you can see what routes are coming in with coupons. Then, you can target those routes with even more circulars. It all comes down to very simple economics - the stores see value in sending out the circulars because they can see that customers are coming in with coupons from the circulars. What you need to do is go door to door to every home in your route and tell them to never use the circular's coupons. Then, the store will figure that the route is not worth it and stop sending the circulars to your route. This is identical to the email spam problem. The only way to stop it is to go to every person with an email address and tell them to stop buying stuff advertised in spam. When the profits dry up, so will the spam. -- kainaw™ 20:56, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Actually it's a lot easier to fight junk mail then it is to fight spam. Unlike with spam which is very international the vast majority of junk mail is fairly local at worst national but mostly even more localised. As such, laws restricting the delivery of junk mail can be much more effective. Furthermore, unlike with spam which is generally sent out anonymously by people who don't give a damn about their reputation many senders of junk mail to have a reputation they want to preserve and are not anonymous. As such a combination of legal means and public pressure can ensure that things such as 'no junk mail signs' are respected. As for addressed junk mail (which appears to be a major problem in the US) I would suspect asking to be unsubscribed from the list (as well as the necessary public and government pressure to ensure such requesteds are respected) can ensure the problem is greatly reduced so it is at worst a minor annoyance with the occasional 'junk mail' that slips through. Nil Einne (talk) 08:58, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

- Actually, some private mailbox companies (e.g. the UPS store) will filter out bulk mail. You will probably pay more for the privledge though. Dragons flight (talk) 15:30, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

Half of the stuff does not have a name or address on it and no postage of any kind so how do you tell if it was put in the box by the post office or by a private carrier? Isn't there a postal regulation that says anything without postage can not go in the box? 71.100.14.54 (talk) 03:36, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

- I suspect not. However if you're only talking about unaddressed mail, you may want to lobby either your postal authority for your PO Box or your government to pass a regulation or law requiring a no junk mail sign to be respected. There is already be such a law in New York in the US although it won't come into effect until January 2008 [2]. In Dallas/Texas, these sites may help [3] [4] and you may also want to follow the advice above. In New Zealand a combination of government and public pressure has meant that such signs are generally respected. [5] [6]. Nil Einne (talk) 08:58, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

Some objects I can see through my telescope at what magnification?[edit]

Hi. What celestal objects (eg. planets, deep-sky objects, comets, etc) can I see with a 114 mm reflector, and when? I'm not asking you to list all of them, just some good objects to look at during different times of year. The thing it, I can calculate limiting magnitude, and I can calculate surface brightness, but I can't calculate if the two correspond in a way so I can see the object well, or what bagnification I should use. Ok, I will list the magnifications and approximate FOVs here, FOVs in arcmins:

- 36x, 100

- 60x, 50

- 72x, 50

- 90x, 30

- 120x, 25

- 144x, 25

- 180x, 15

- 240x, 12

- 360x, 7

So, which objects should I look for, and at which magnifications? Yes, i know that aperture is more important, but I already set the aperture by buying the telescope, although it can be closed down to 57 mm if required, and I doubt that would be nessecary. Thanks. ~AH1(TCU) 01:00, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Maybe this website will help: http://www.astro-tom.com/getting_started/what_to_look_at.htm

- The Transhumanist 02:10, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

Telescope lenses/eyepieces' optical coating[edit]

Hi. Is it important to avoid scratching or touching the lenses/eyepieces' coating? Is the coating so important that the eyepiece/lens would be effectively useless/very poor quality without it? How does lens paper work, how does it prevent you from touching the lenses while using it to clean them, and about how much do they usually cost? Would washing or wiping lenses with a household tissue damage the coating? In an average eyepiece, approximately what percentage of its value belongs to the plastic components, the rubber components, the glass of the lens, the optical coating, and the metal components? Is the coating's job to allow more light to pass through, to supress false colour, to allow clearer images, etc? When an eyepiece says it has three-, four-, five-, etc element design, does that refer to the glass or the coatings? Are eyepieces perfectly symmetrical in terms of the shape of the glass parts, in all lines of potential symmetry, viewed from above, or do the optical element design cause it to be slightly not symmetrical? Oh, and as an aside, when my telescope is polar-alighned, on my telescope's RA slow-motion controls, when I rotate the knob clockwise, the RA number that it is pointed to goes down, and when I turn it counter-clockwise, the RA number goes up. Which way do I turn it to follow the Earth's rotation? Also, both on the left and right of the 90 mark for decilnation, the numbers go down from 90, go down to 0 on both sides, then go back up to 90 on the other side. I think one of the 90s is north pole, and the other one is south pole. I think i know which one it is, but when I point to an object with a specific declination, in which direction should I turn so that the declination lines up, or should I experiment with both and use the one that makes sense? Thanks. ~AH1(TCU) 01:19, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- See this web page on cleaning telescopes. The Transhumanist 01:57, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

Twelve Days of Christmas[edit]

Are the Twelve Days of Christmas related to the twelve day difference between the Solar and Lunar Calendars (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lunar_calendar)? I heard this this holiday season and I have been unable to verify it.208.46.64.238 (talk) 05:59, 20 December 2007 (UTC)Scott

- No. The Twelve Days of Christmas are the days between the ecclesiastical holidays of Christmas and Epiphany. - Nunh-huh 06:29, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- (edit conflict) I was about to post those same links. But as I understand it, the origin of setting Christmas and Epiphany to those specific days is not well understood. Clearly the date of Christmas is related to the winter solstice, but why was Epiphany set to be January 6? And why is Christmas not quite on the solstice? I don't see why the two holidays couldn't be related to a solar/lunar calendar difference. I have no idea why those dates were chosen, but the fact that the date of Easter is lunar based to this day makes the solar/lunar theory about Christmastide seem at least plausible to me. My suspicion is that no one knows for sure why those dates were chosen, so no one knows why there are 12 days. But what do I know? Pfly (talk) 06:50, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- "The solar/lunar calendar difference" refers to the difference in year lengths, not to the date offset for any particular year. That is, if a lunar-based event was on January 6 one time, it might be on December 25 the next time, but then the time after that it would be on December 13 (or maybe about January 11, depending on leap months in the lunar calendar). Which means it doesn't seem like a likely basis for anything. --Anonymous, 07:10 UTC, December 20/07.

Christmas falls on December 25th because the early Christians adopted that date from another religion - something that Christianity has done a lot of throughout history, and especially in the Early Christian period. The "other religion" that I mentioned was Mithraism, which was an enormously popular and influential religion during the late Roman Empire. Indeed, when Constantine chose to make Christianity the official state religion, there was a debate as to whether to select Christianity or Mithraism, since many more members of the Roman military practiced Mithraism, and Christianity was for the most part viewed as a Slave Cult by the Roman elite at the time. However, be that as it may, the reason that December 25th became the date that Jesus was supposed to have been born on is due to the fact that that was the date that Mithras was supposed to have been born on, too.

When I say that Christmas came from Mithraism, I should insert a comment that it was actually indirectly from Mithraism. Christmas being celebrated on December 25th really came directly from the Roman festival known as Sol Invictus. However, this celebration was created by the Romans to more or less bring together a bunch of different Winter Solstice celebrations from various religious traditions throughout the empire, including Mithraism. The reason it was celebrated on December 25th (as opposed to any other date near the Solstice) was due to the influence of Mithraism, though - it was Mithras' birthday. So when Christianity adopted Sol Invictus to be the date that Jesus' birth was celebrated, it was actually going back to the birth of Mithras in a roundabout way.

Now, as to why Mithraism celebrated December 25th as the date that Mithras was born - that's another story. If I have time I'll write more about that later. -- Saukkomies 10:13, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

acidic?[edit]

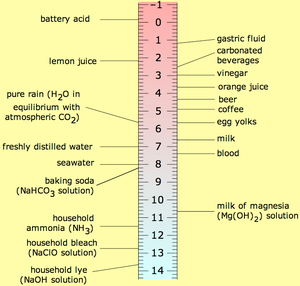

Red is acid, Blue is alkaline

I know that Lemons, and Oranges, for example are acidic and so affect my arthritis pain, but I like apricots, are they acidic please--88.110.51.242 (talk) 09:40, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Apricots have a pH of about 4, so yes, they are acidic. However, this is much less acidic than a lemon (pH 2). Since pH is measured on a log scale, that would make apricots about one percent as acidic as a lemon. Of course, I can't say what that means for your pain, you'll have to try yourself or ask a doctor. Someguy1221 (talk) 09:57, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Thanks Someguy, you were quickly on the ball this morning! Can I now ask you the same question about bananas and dates. Thanks in anticipation.--88.110.51.242 (talk) 11:29, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- This website lists pH values for various foods. May I ask you how the pH of your food is supposed to affect your arthritis pain? Icek (talk) 14:21, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- I should explain - that the acid ('gastric fluid') that naturally forms in your stomach to aid digestion has a pH of between 1 and 2 (see the scale to the right here). This is FAR more acidic than oranges and lemons and FAR, FAR more acidic than Apricots. Since you don't digest any of the food between chewing it and getting it into your stomach, there is no possible way that these acidic foods can be affecting your arthritis because of their acidity. It's possible that some other substance in lemons and oranges are the cause of your problems - but for sure it's not the acidity. If you seriously worry about this - see a doctor because we aren't allowed to give medical advice. SteveBaker (talk) 15:16, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

Addresses[edit]

What, please, are the component elements of the addresses on these pages, and why does my address change occasionally?--88.110.51.242 (talk) 09:49, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- The addresses are called IPs, and it will change from time to time if yours is dynamic. Someguy1221 (talk) 09:56, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- If you wish to stop the IP appearing next to your name you could always register an account and then get a name after all your comments!TheGreatZorko (talk) 11:53, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Every computer on the Internet has a unique number assigned to it in the form of four bytes - those are the four numbers that you see with dots between them. If you don't have a user account, Wikipedia uses the four numbers that describe your computer to identify you instead. If your computer is connected through a low-cost Internet Service provider then it's likely that your IP numbers will change from one time you turn on the computer to another - or possibly from one day to the next. If you have a "static IP" (as I do) then the numbers stay the same. The first number out of the four (88 in your case) can be looked up on this handy-dandy IP chart: xkcd.com (there are better ones - but this one is fun!). 88 says that your internet provider is probably in Europe somewhere. The remaining numbers tell you less and less information. Probably, the second number never changes (or perhaps changes between a couple of different numbers) which identifies the Internet Service provider you use - or perhaps the company you work for or the school you attend. The remaining two numbers are probably allocated more or less at random amongst the computers connected to that provider. This is a slight over-simplification - some companies have the first number all to themselves (IBM, for example) and all three of the other numbers are available for them to allocate to their users (this is called a "Class A" IP address) - other companies are given the first and second numbers and they have the third and fourth to allocate to users (Class B) - really small organisations have the first three number handed to them and can only allocate the fourth number to their users (Class C). SteveBaker (talk) 13:02, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- The OP uses Tiscali in the UK. DuncanHill (talk) 13:16, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- You are right, but how do you know?--88.110.51.242 (talk) 13:21, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- If you click on the numbers after your posts, you are taken to a page which lists all the contributions made to Wikipedia from that IP address. Near the bottom of the page are a series of link in blue - click on them (I clicked on WHOIS) and you will see information about the IP address. DuncanHill (talk) 13:27, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- It's interesting to note that when you use Wikipedia 'anonymously', your IP address tells people far more about you than if you had created a user account! I won't use your IP as an example - so let's see what you could find out about me if I were to edit "anonymously": Well you'd find out that the IP address of one of my computers at home is 66.137.234.217 - and from that, you can go to a 'WHOIS' server (just Google 'WHOIS' and you'll find a bunch of them) - and you'll discover that I use AT&T internet services via SBC and that my real name is Stephen Baker - not User:SteveBaker (only my Mom calls me "Stephen" and friends are allowed to drop the more formal "User:" part!). With some WHOIS services you can also find out that this address is located in Dallas, Texas (well, it's actually about 15 miles outside of Dallas - but close enough!). So by using my IP address, you already found something that you couldn't have known from my Wikipedia username alone. You could also type in http://66.137.234.217/ into your browser and see if that person has a web server running (which I do - but it's cunningly set up not to respond with an actual web page unless you know the URL)...and because Apache tells you who the 'webmaster' for the site is, you've got my email address...(Darn! I need to fix that!). You could also use the IP address to launch all kinds of nasty attacks on their computer (I'm not concerned because I have a fairly impregnable Linux box protecting the inner network from attack - not a tissue-paper thin Windows 'firewall' package that most people will be running!). So, for pities sake - get a proper Wikipedia account! SteveBaker (talk) 14:14, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Also, you just happen to be editing from a range of addresses associated with a notorious ex-regular here. Some of us are very, very skeptical of anything posted from an 88.110.*.* address, and are apt to delete it if it looks even the slightest bit suspicious. —Steve Summit (talk) 15:04, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Is that better?--Johnluckie (talk) 23:02, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

Physics[edit]

When I was examining a little closed bottle containing Mercury, my golden jewelleries such as chain and ring turned white.Why this happened?<><> —Preceding unsigned comment added by 117.99.7.13 (talk) 10:42, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

Sure it wasn't the philosopher's stone?Shniken1 (talk) 11:04, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- On the face of it, this is impossible - so clearly we're missing some information. Please explain in detail what you were doing and where. Was this in a dark place? Was it in daylight? What other things were in the immediate vicinity? Is your jewelery still white? If not, how long did they take to turn back? How quickly did this phenomenon occur? SteveBaker (talk) 12:48, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- If it's a closed bottle of mercury - and since neither mercury vapour nor liquid is likely to escape (because it's dangerous stuff and people don't store it in things it can escape from) - we can reasonably assume that the mercury had absolutely nothing to do with it. But, mercury is used in places like chemistry labs and industrial settings where there are other chemicals around. Perhaps something else way the cause - but there are very few chemicals indeed that will react with gold. We need answers to our questions - there just isn't enough information here to say anything other than "At first sight - this is completely impossible". SteveBaker (talk) 20:30, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Did you dip your gold jewelery in the mercury? This is bad for gold, as it forms a silver coloured amalgam on the surface. Solid gold sinks in mercury, but it is not worth trying this experiment because of the damage to the surface. The mercury on the surface cannot be removed easily. Dangerous ways to do it are to heat to 300°C to evaporate it, this is not recommended. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 20:39, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

Science/Sound Waves[edit]

How exactly do sound waves travel in air(scientifically)?

- Consider a hifi speaker. It has a cone inside that moves backwards and forwards with the music. When it pushes forwards, it compresses the air that was right in front of it - when it moves backwards, it sucks at the air. When it pushes forwards, the pressure of the air just in front of the speaker cone increases a bit. But the air a bit further away from the speaker is still at normal room pressure - so some of the air just in front of the speaker moves outwards and away from it - slightly increasing the pressure of the air a bit further away. This 'wave' of higher pressure moves outwards from the speaker like ripples on a pond when you toss a rock into it. When the speaker cone moves backwards, it reduces the air pressure just in front of it - and the air a bit further out in the room is at higher pressure - so the air moves backwards towards the speaker - and now the air a bit further away is lower pressure than the rest of the room. So now a wave of lower pressure air spreads outwards. As the speaker cone moves in and out (many hundreds or even thousands of times per second), it creates alternating high and low pressure waves that ripple outwards into the room. Individual air molecules move back and forth but not by very much as the wave passes by. When one of these air pressure waves hits your ear, the eardrum is either pushed in or sucked out as the air pressure varies - this causes minute hairs inside your inner ear to wave back and forth. The longer hairs respond to lower speed changes the shorter hairs to faster change - each is connected to nerves that detect it's motion and send this as "sound" to our brains.

- Scientifically - well, the pressure waves move at the speed at which air can respond to rapid pressure changes - and that is what we call "the speed of sound" which is around 300m/s (700mph) at sea level depending on the ambient air pressure. The rate at which speaker cones (and therefore sound waves) move in and out is the frequency of the sound - which (for humans) ranges from about 50 times per second up to perhaps 20,000 times per second (the highest frequency you can hear depends on your age - mostly). Sound waves work at much lower and much, much higher frequencies too - but our ears can't respond fast enough (or slow enough) to pick them up. Since frequency and speed are related, we can calculate that the individual waves of higher and lower pressure are anywhere from six meters long for the lowest frequencies we can hear down to a centimeter or so for the highest frequencies. So imagine these small pressure changes racing outwards from your speakers (or anything else that makes a noise) at 700mph - in bands like waves on a pond, but anywhere from big waves - 20 feet long to tiny ones under an inch. Ripples in a pond spread out in a circle because they are fixed in two dimensions to the surface of the lake. Sound waves can go off in all directions - so they spread outwards like rapidly growing spheres. Since the area of a sphere grows by a factor of 4 every time you double it's radius, the power of the air pressure changes from your speakers spreads out over 4 times the area every time you double the distance from the speaker. So sounds get rapidly quieter as you move away from the sound source. This is called the "inverse square law" - the energy in the sound decreases by a factor of one divided by the square of the distance from the source.

- Like all waves, sound can be refracted, reflected, focussed and sound waves can interfere with each other. Just as light can be spread out as it moves through a narrow slit, so sound waves are spread as they move through a narrow opening. Compared to the sizes of sound waves (6 meters down to a few centimeters), relatively human-size 'slits' can cause sound to do this. That's why sound can pass through an open doorway - and then spread outwards from there into the room beyond. When sound waves are reflected, we call that 'reverberation' or perhaps an 'echo'.

- SteveBaker (talk) 13:52, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

Freezing point of petrol[edit]

At what temperature does petrol freeze? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 193.62.43.210 (talk) 14:47, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Jet fuel is listed as freezing at −47 °C (−52 °F). Someone responded on this site that gasoline freezes at −84 °C (−120 °F), which could be possible because jet fuel is quite different than gasoline. -- MacAddct 1984 (talk • contribs) 14:55, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- This is a lot harder to answer than you might think! Petrol is a complicated mixture of a lot of different compounds - all with different freezing points. There are also a bunch of different additives that change those freezing points and which differ from place to place and season to season. I've seen figures ranging from -80F (-62C) to -300F (-180C) in different places on the net. Note that even the highest estimate (-80F) is colder than the coldest temperature every recorded in Europe or the USA...so the accidental freezing of petrol on a cold winter morning is not a great concern! I believe that it's fairly common for Diesel fuel to freeze in very extreme conditions though and some diesel powered arctic vehicles have tank heaters for this reason. SteveBaker (talk) 15:04, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Diesel fuel doesn't really freeze but rather "gels" as the various heavier fractions (waxes and the like) freeze out. We don't appear to have a good description of that in the encyclopedia yet. Anti-gelling agents are available that lower the "gel point" of a given fuel; I suppose they're solvents of some sort or another.

- Many of the anti-gel compounds are alcohol based, but their use is problematic (in that they often don't work). A larger issue for diesel powered engines (particularly large commercial vehicles) is ice forming in the fuel lines, and alcohol works quite well for that. The best solution (for the engine, not so much for the rest of us) is to periodically idle the engine overnight to keep the fuel moving. As long as it is moving it won't gel and no ice will form. 161.222.160.8 (talk) 00:44, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

Allergens[edit]

A few questions about allergens:

a) There are many peptide hormones in the blood plasma - so I guess there is a common region in these peptides which is recognized as "self" by the immune system. How is this region called (the large major histocompatibility complex is only on cell surfaces)?

b) If the allergen is in the food, how does the protein come into the blood stream? How much of the protein is digested and how much is able to cross the lining of the intestines?

c) What is the minimal plasma concentration of an allergen needed to cause a notable allergic reaction?

Thanks in advance for the answers. Icek (talk) 15:17, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Why do you think there is a common region in peptide hormones? One way to get large molecules across epithelial cell layers is transcytosis. --JWSchmidt (talk) 16:09, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- (a) To act as an antigen or allergen, a substance has to either be internalized (phagocytosis, pinocytosis) and presented to T-cells by antigen presenting cells, or, if it is a small molecule, to interact chemically with a larger molecule and act as a hapten. A relatively small molecule like a peptide simply doesn't trigger an immune response by itself. And yes, the molecules of the MCH reside in the cell membrane.

- (b) and (c) As far as I know, proteins are generally absorbed as single amino acids or very short peptides. Allergic reactions generally happen on mucosal surfaces or on the skin. When an allergic reaction leads to anaphylactic shock, it is because cells in the mucosa release chemical mediators which have a systemic effect. --NorwegianBlue talk 16:18, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

For A: There is no common region of peptide hormones (or other peptides) that are recognized as 'self'; rather, the 'self' peptides are not recognized by the immune system as 'non-self'. The determination of self/non-self is not made by the allergen but is actually made by the immune system. That's why some peptides which are clearly 'non-self' are not always recognized by the immune system, they may not be good antigens.

For B: There are various methods for proteins to make it into the blood as larger fragments, although they are usually absorbed as very small peptides.

For C: There is no minimal plasma concentration of an allergen needed to cause an allergic reaction. The level of antigen needed to cause a notable reaction is based on the strength/method of interaction between the immune system and the allergen. This naturally means that necessary plasma level will vary between individuals for any particular allergen and even vary in a single person over time. Often, allergic reactions in a person worsen with subsequent exposure to a previously encountered allergen due to the immmune system being primed. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 142.36.194.253 (talk) 17:27, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

Thanks for the answers so far, but unfortunately they provoke a few more questions. If the allergen acts on immune cells on the mucous membranes, what's the minimal concentration there which causes a notable allergic reaction? And what's the minimal amount (per kg body mass) to cause an anaphylactic shock?

Are there measurable quantities of food proteins or large fragments thereof in the blood after a meal (in "normal" people and in allergic people)?

To 142.36.194.253: Do you seriously want to tell me that 1 protein molecule per liter is able to cause an allergic reaction?

Icek (talk) 07:08, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

- A small correction to my previous reply: if a person already is immunized, and has IgE attached to Mast cells in the mucous membranes, anaphylaxis is triggered merely by the interaction between the allergen and IgE molecules attached to Fc receptors in the cell membranes of the mast cells. But for immunization to occur in the first place, you need the T-cells as stated previously. When mast cells degranulate, the release of chemical mediators (histamine, cytokines) leads to allergic symptoms and possibly anaphylaxis. The degranulation of mast cells is very easily triggered, as was evidenced by the controversial Nature paper by Jacques Benveniste. I'm not aware of any studies addressing minimal concentrations, and I doubt that focusing on plasma concentrations is relevant, since the action occurs in the mucosa. --NorwegianBlue talk 16:20, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

Sorry, I wasn't trying to say that a single protein molecule would result in an allergic reaction. What I was trying to say is that there is no defined minimum protein level. It is not possible to say that 10000 (substitute any number you like for 10000) molecules of protein per liter will cause an allergic reaction. This number would vary by person and the nature of the allergen. You might be able to measure something like "for person X, Y amount of protein Z per liter will cause an anaphylactic reaction" but generalizing it for the whole population/different proteins is not possible.

- Do you have any information about the minimal concentration over all humans? I. e. the concentration needed for people who get a reaction at the least concentration compared to other people? Icek (talk) 10:25, 25 December 2007 (UTC)

Our Solar System[edit]

I have 2 questions, are there possibly more planets in our Solar System that we haven't discovered? And also, does our solar system have a name? Ts41596 (talk) 15:19, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- It is extremely unlikely that there are any other planets in our solar system. If there was, we would have seen something by now. However, there are theorists that claim there could be one directly behind the sun all the time or one that buzzes by once every 1,000 years and then heads off into deep space. Chances of those are basically 0%. As for the name of our "planetary system" - it is called the "Solar System." -- kainaw™ 15:25, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- The naming issue is similar to "the Moon". A planet's orbit behind the sun at L3 wouldn't be stable - it would probably have collided with Earth long ago. A planet with an orbital period of 1000 years would have a semi-major axis of only 100 AUs which means that the distance is maximally 200 AUs at any point of its orbt - a large body at such a close distance would probably have been spotted already. Compare with the planetoid 90377 Sedna (its diameter is only about 1500 km) which has an orbital period of about 12000 years and a maximal distance from the sun of 976 AU. A planet in a Sedna-like (or even larger) orbit is a bit more likely than the other possibilities. Icek (talk) 15:36, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- It may be worth clarifying that (thanks to the new IAU definitions) there are almost certainly more dwarf planets to be discovered in the solar system, as those can be small and distant enough to elude casual detection. — Lomn 16:14, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- If the planet is small enough and far enough away - yeah - there could definitely be more. 90377 Sedna was only discovered 4 years ago - and it's much bigger than Pluto (which was once a planet) - also Eris (dwarf planet), (136472) 2005 FY9, (136472) 2005 FY9, all of them found just a few years ago and comparable in size to Pluto. Given that we are still finding bodies that are large enough to qualify as planets (if that were the only criteria) - then it's very likely that we'll find many more - and that one or more of them will qualify under the new, more complex rules for deciding what counts as a planet. SteveBaker (talk) 16:49, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- With the current rules (specifically, with the "cleared the neighborhood" clause), I think it unlikely that anything found will be a planet rather than a dwarf planet. The effects of something that gravitationally significant should already be observable. Of course, there is that ever-pesky problem of "should" not always being equivalent to "is".... — Lomn 17:19, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Perhaps gravitational effects have already been observed - see Kuiper cliff. Gandalf61 (talk) 17:28, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- I remember discussing this with someone, and I believe the current observation limits for "dark" planets (albedo ~0.04, like dark KBOs) is something like "No Mars or bigger within 100 AU". Given the Oort Cloud extends to ~10 000 AU, and many of its bodies never get anywhere near the Sun, Pluto - Earth sized bodies "could" exist in the Oort Cloud - although I'm not sure it's particularly likely, its within the realm of the "not crazy". WilyD 17:35, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

Just a note on Pluto having been "once" a planet. It is what it always was, whatever that was. IAU has no authority to define what "planet" means (nor does anyone else, of course). Their decision will have effect only if the rest of us let it. I say resist, and down with international bodies that try to standardize such things. (Luckily, there's none in mathematics.) --Trovatore (talk) 21:27, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- What would your attitude be if everyone went back to including Ceres in the list of planets in the solar system, Trovatore? Or 2 Pallas, 3 Juno and 4 Vesta (all once called "planets")? Or the hundreds of thousands of other asteroids since discovered? Surely it's appropriate for there to be a taxonomic scheme that distinguishes between objects of major gravitational influence (and commensurate scientific interest) and those of minor influence and interest; otherwise every speck of dust could legitimately be called a planet and there'd be chaos. Everywhere else in science, a fundamental discipline is to "define your terms". If the IAU isn't an appropriate forum in which such a scheme can be negotiated and agreed on, and such terms can be defined, what is? -- JackofOz (talk) 22:07, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- What do you think a planet is then? Why do you think it was a bad idea to clearly define planethood scientifically rather than working on vague laymen terms. By the way does having the status of dwarf planet make Pluto any different from what it was earlier. Does it belittle it in any way? I don't think so. In fact, it is now known as second largest dwarf planet in our solar system, which should make you happy on behalf of Pluto. Why do you feel bad? Planet, dwarf planet, asteroids etc. are just useful definitions for astronomers which they had to agree upon eventually observing that there are so many bodies revolving around sun, so they had to set up clear definitions of everything. Also, this was not a decision of single person, the whole body of world's scientists was involved in it. Though there were debates, but they were all for new definitions of planethood and eventually everyone agreed. Pluto is still happily revolving around the sun. DSachan (talk) 22:28, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- So I admit I would have been happier if they had gone with the other proposal, that would have admitted fifty or so planets. But my main objection is to the fact that they promulgated a definition at all, not the particular one they picked. This is just improper. Scientific definitions are not chosen by votes -- they evolve, depending on who writes what papers and who picks up the terminology therein used. That's the way it should be. I completely disagree that there was any need whatsoever to "officialize" a choice of definitions. --Trovatore (talk) 22:38, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- It's not exactly unknown for old traditional ways of doing things in science to be revolutionised in response to emerging circumstances. Some of the members involved at Prague agreed with your stance, Trovatore. But the majority of members (a) thought there was a need for a definition, (b) thought the IAU had the authority to come up with one, (c) thought they should use their authority, and (d) chose one. Many people will say that the IAU has only 63 member nations and therefore doesn't represent the entire planet, and in particular it doesn't represent them personally. That's a fair call. But it is internationally considered to be the body that has status in this area. Still, you're right - legislating for words is not ideal; and people are free to give Pluto etc whatever names they like; they won't be fined or put in prison if they keep on calling it a planet. They might just be out of step with the majority of their peers who have chosen to let go, move on and adopt the new definition. -- JackofOz (talk) 23:03, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Are you opposed to the idea that they changed the definition of planethood or the fact that Pluto is now no more a planet? At one place you write, scientific definition should evolve and in the very beginning you write it would have made you happier had they termed all bodies as planet and eventually including Pluto. If you stick to your opinion that scientific definitions should evolve, then their other planethood definition also should not make you happy. And then what makes you think asteroids also should not be called planets? By the way, the word planet was introduced by ancient astronomers, so you naturally could not have expected a solid scientific definition for it right from the beginning, and we saw that its definition was actually getting entangled with those of new solar bodies as they were being discovered. Either you had kept calling everything planet that revolved around the sun right from the beginning but that would have been injustice to specks of dust which also tirelessly revolve around the sun or you had defined its definitions clearly. The problem is that the word planet is ancient (unlike modern scientific neologisms, which are already well defined) and if you expect any single person to come with few definitions of it as a process of evolution, why would all other scientists agree to accept it? Will it not be another case of voting if eventually votes are cast. If this is not done, there will never be consensus on definitions of old words which are incorporated in science. It is just like the definition of flowers or animals. These words also originated in ancient times, but later they were incorporated in scientific studies. Their definitions are still vague. DSachan (talk) 23:18, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- The definitions of flowers and animals are vague, and that's just fine; they ought to stay that way, until and unless more precise definitions evolve by the natural process of one researcher using them and other researchers adopting them. In practice, of course, no biologist is going to propose a precise definition of "dog" and try to make it into a technical term of art. Rather, they propose new names and give them definitions.

- The definition of "planet" was vague, and should have stayed that way. New terminology could have been created for more precise meanings -- but again that should go through the natural process, not the vote of some silly international body. --Trovatore (talk) 23:51, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Prior to 2006, the scientific definition of planet wasn't even vague, it was non-existent. The general populace uses words to mean whatever the heck they want them to mean, which is how language constantly changes and evolves. But we're not talking about the general meaning/meanings of "planet", we're talking about the scientific/astronomical term "planet", which had never been formally defined before. Why should vagueness reign supreme over precision where it's possible to be precise? That doesn't sound like a good approach at all, particularly in scientific matters. -- JackofOz (talk) 00:02, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

- If they needed a more precise notion they should have given the notion a different name. Unless of course it was in a context where it was clearly a term of art -- when I talk about a huge cardinal I don't simply mean a cardinal that's really really big, even though of course it is, but hopefully it's obvious in context that it's a term of art so it's not a problem. But even with a different name it shouldn't be done by getting people together and voting (or by any other formal procedure). --Trovatore (talk) 01:54, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

- Believe it or not, but naming disputes in astronomy, biology, and chemistry have been routinely resolved by voting (or similar consensus finding exercises) among groups of specialists for a long time. It is useful in general for scientists to have an agreed upon nomenclature, and in this case astronomers felt a need to agree on a meaning for "planet". You can ignore their definition if you like, but the academic journals respect the judgment of the International Astronomical Union and require that papers for publication follow their nomenclature. Hence, that "silly international body" is binding on academic publications. Overall, this agreed upon precision facilitates communication between specialists. You can choose to ignore it if you wish, but after a while you are just going to sound ignorant. Dragons flight (talk) 02:10, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

- If they needed a more precise notion they should have given the notion a different name. Unless of course it was in a context where it was clearly a term of art -- when I talk about a huge cardinal I don't simply mean a cardinal that's really really big, even though of course it is, but hopefully it's obvious in context that it's a term of art so it's not a problem. But even with a different name it shouldn't be done by getting people together and voting (or by any other formal procedure). --Trovatore (talk) 01:54, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

- Prior to 2006, the scientific definition of planet wasn't even vague, it was non-existent. The general populace uses words to mean whatever the heck they want them to mean, which is how language constantly changes and evolves. But we're not talking about the general meaning/meanings of "planet", we're talking about the scientific/astronomical term "planet", which had never been formally defined before. Why should vagueness reign supreme over precision where it's possible to be precise? That doesn't sound like a good approach at all, particularly in scientific matters. -- JackofOz (talk) 00:02, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

- Probably because there is no need since issues that require it don't arise (most definitions of mathematics are. BTW, I don't get why you're that opposed to formalisation. In reality a lot of what you now consider 'natural' occured in similar ways (for example, many changes occured because one or two people made a decision and everyone followed not necessarily because everyone agreed or because the decision made the most sense but because this people were then the pre-eminent scientists of that area and no one even considered going against them). Indeed the metric system is another thing that was designed in a resonably formal way and continues to be and I for one and glad of it compared to the extremely ugly 'natural' systems still in use today (although again ironically even these systems that 'evolved' naturally had a lot of formalisation and are defined based on the metric system). Scientists need to have a way of communicating clearly. And in reality, the officialisation that you derise is often a lot fairer and more robust then the alternatives which often mean that a few select people (such as editors) get to have an undue influence on terminology despite the fact that they may not be the ones doing the work and often means scientists from countries outside the western hemisphere have virtually no say. BTW, have you ever used the term huge cardinal to have some other meaning in a paper? Do you think your paper is going to be accepted? In reality these terms probably didn't just 'evolve'. Instead their definition made sense to a number of people and this definition was probably 'enforced' by journals and the like. In reality I strongly suspect that even very early on when these terms which began to take on a meaning you would not have been able to use the terms in any other way without having your paper rejected outright. A lot of stuff occurs in this way and there's absolutely nothing wrong with it even if it isn't 'natural' according to you. (In biology for example, the first person to discover a species and write about it is usually the one that gets to name it. Sometimes people may not like the names for various reasons but thankfully most people accept this system even if is 'unnatural' and too formalised for your liking. Nil Einne (talk) 09:02, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

- (unindent)

- Scientific use of words needs to be precise. But science's use of words doesn't have to agree with those of general society. The word "accellerate", for example, mean "go faster" to non-scientists - but to a physicist, it can also mean "go slower" or even "turn a corner". Science has a precise meaning of accelleration which is something like "rate of change of velocity as a function of time". This kind of thing happens all the time. Lots of people don't think of insects, birds and fish as "animals". (See for example "All about Animals and Insects", or http://www.birdsandanimals.com/ who aparently train "Birds and Animals" - or there is the PetLovers.com thread where someone asks whether fish are animals or not). Scientists have a very precise meaning for the word 'animal' (They are life-forms from the kingdom EukaryotaAnimalia) - but the public don't. Did we have a huge amount of anger when taxonomists decided that Mushrooms aren't plants anymore? I don't think many people outside of the scientific world even realise that it happened! Did vegans have to decide whether they should stop eating mushrooms because they aren't plants anymore?

- The same thing happened with the word "planet". The original meaning of the term was "Wanderer" - ie "stars" that don't stay put like the others. In popular usage, the word had a rather vague definition. We had said that Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto were obviously planets and kinda left it at that. But astronomers are now finding things that are smaller than Pluto, yet which orbit the Sun and are much larger than any of the asteroids we ever saw before. What do we call those things? What if one (like Sedna) turns out to be bigger than Pluto - does that make it a planet? What about if one is 10% smaller? 20% smaller? Just how small does it have to be? What about the problem of our own moon ("Luna")? Our moon is a LOT bigger than Pluto - if Pluto is a planet, then why isn't Luna a planet too? There is a pretty strong case for saying that if Pluto is a planet then the Earth/Luna system is a binary planet. That would mean taking away the name "Moon" from our moon...but if you think demoting Pluto was unpopular...telling people that "The Moon is not a moon anymore" would have caused rioting on the streets!

- This was never a problem in the past because everything was very clear-cut - there were these nine things that had always been called "planets" and that was that. What about an Earth-sized object that's just drifting through space - not orbiting anything at all? Is that a planet or is it a giant meteor? What about a star that's used up all of it's energy and is now drifting through space as a brown dwarf - is that now a "planet" or is it too a "meteor" or is it still a "star"? Does is make a difference if the brown dwarf is orbiting another star? Then we have this huge number of 'exasolar' planets - orbiting other stars. Some of these are MUCH more massive than Jupiter - and it's possible that one day we'll find one 50 times as big that will be capable of fusion reactions at it's core that would make it be a kinda borderline star.

- So we have this huge number of weird things out there that need names. Scientists need to be able to say that such-and-such is a "planet" and from that statement, know a large number of things about the object. There were plenty of ways the term could have been nailed down (some of which I'd have preferred) - but in the end, they either had to define "planet" formally or invent entirely new words for large things orbiting around stars and to use that word instead of "planet". Personally, I'd have picked a definition with a minimum mass limit that would include Pluto and a rule that it has to orbit a star and for situations like Earth/Luna or Pluto/Charon where both objects might be classified as planets that their barycenter must lie outside of both bodies in order to count both as planets. That definition would have left Pluto as a planet and admitted Sedna and a few others to the list. What we have now is kinda ugly and a bit open to interpretation. We're still not sure whether some of the new 'Dwarf planets' are really proper planets or not - and it'll be a very long time indeed (if ever) before we know whether these extrasolar planets are really planets or not. (It's going to be embarrasing if something 3 times larger than Jupiter has to be called a "dwarf planet" because it hasn't yet cleared out it's neighbourhood of debris!).

- The general public are still perfectly able to go on calling Pluto a planet if they want to - it's not like a law was passed or anything. The intent of the change is that astronomers and other scientists can describe all manner of weird objects with a little more precision in formal situations. The general public don't go around calling the Sun a "Star" either. Oh - and if you want, I won't insist that you call the brake pedal and steering wheel of you car "accellerators".

- SteveBaker (talk) 16:12, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

- I disagree that there was any such need. Analogy: Some mathematicians consider zero a natural number; others do not. This difference in terminology does not correspond to any mathematical difference of opinion whatsoever -- it's purely a difference in use of language. If some international body, say the International Mathematical Union (which actually I've never heard of anywhere but Wikipedia), were to pick one or the other and claim that this is now the official definition, we'd have their heads on a platter! Even if they picked the correct definition, which of course is that zero is a natural number.

- Does it ever matter which definition you pick? Sure; if you're thinking of one definition but applying a theorem that assumes the other, you could get something wrong. But in that case it's almost always obvious from context, or from thinking about it for five seconds, which definition is being used. If it's not, then it's the responsibility of the author to make it clear.

- I see no reason that couldn't work for the term "planet" as well. And I note in particular that the two proposed criteria, the "clearing the neighborhood" criterion and the "sufficent gravity to pull itself into a sphere" one, did not respond to any study of bodies meeting those criteria in ways that differed from others, but were simply an artificial attempt to find some demarcation, so that they could promulgate a definition. But no definition was in fact needed. --Trovatore (talk) 18:13, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

- If you want to get technical about it, the defintion of "planet" has evolved and been accepted by consensus just like any other definition. Would you have been so irate if some notable scientist had started using a particular definition of "planet" in his papers, and his peers said "Hey, we like that definition, it works, and we really do need some definition so we all know we're talking about the same thing, so let's use that one"? That's pretty much how you have stated that definitions of terms do/should come about, so I think it's fair to assume you'd have no problem with that. So why are you so antagonistic when instead of one scientist it's a group of scientists, and they went about it in a bit more organized fashion? It's still the consensus of the scientific community that's accepting or rejecting the definition. If they'd said, for instance, that a planet is something with moons, thereby excluding Mercury and Venus and including a couple of asteroids, that definition would not have been accepted by astronomers, and ignored out of existence. It's really a matter of the IAU saying "here, this works" and the astronomers saying "yeah, that's pretty good" and using it. The method of acceptance (or rejection) is the same; the only difference is the definition coming from a scientific group rather than from an individual, or a journal editorial board, or whatever else. And for the love of Jupiter, why does it matter to you if astronomers decide to pick a group of their peers to work out common definitions for things so when they say "dwarf planet" in a paper, for instance, everyone knows what they're talking about without having to read their unique definition of what a "dwarf planet" is? It works for them, and those of us who are not astronomers really don't have any standing to say that is or isn't how it should be done.

- Worldwalker (talk) 18:20, 25 December 2007 (UTC)

- Pardon me for butting in, but your discussion is a hell of a read, guys.

Thanks!--Ouro (blah blah) 18:43, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

What's the main cause of passengers' death in a plane crash?[edit]

Is it the fire? Or the impact? Or any other reasons? Some statistics would be great. Thanks for your answers. roscoe_x (talk) 17:57, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Per David D., it depends on the type of crash. You might find some of the links in Aviation accidents and incidents useful, though. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 18:13, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- But I think it's safe to say that impact and fire are the two major causes in accidents that cause major loss of life, and probably ranked in that order. --Anonymous, 01:12 UTC, December 21, 2007.

Water breathing[edit]

How much water does the average person exhale per day? GeeJo (t)⁄(c) • 18:54, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- See breath. The average breath is 5% water vapor by volume. See respiratory minute volume. The average person exhales 5-8 liters per minute. There are 60 minutes in an hour and 24 hour in a day - so there are 1440 minutes in a day. The average person exhales 7200-11520 liters of air per day. 5% of that is 360-576 liters of water. That sounds high, right? So, look at lung volumes. The average exhale is 500mL. In respiratory rate, the average person exhales 12-20 times per minute. That is 6-10 liters per minute, which is pretty much what the initial average was. So, assuming the numbers are right, your answer is 360-576 liters. -- kainaw™ 21:08, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Dude, you might throw in a little reality check here. Do you drink 100 gallons of water a day? Or consume 800 pounds of anything? Then how is that much water going out your lungs? Come on, this sort of checking is an essential part of real-world calculation. --Trovatore (talk) 21:12, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- That's 360-576 litres of water in gas form. i.e. 16 - 26 moles of water - i.e. 288 - 468 grams of water. Half a pount to a pound. WilyD 21:19, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Dude, you might throw in a little reality check here. Do you drink 100 gallons of water a day? Or consume 800 pounds of anything? Then how is that much water going out your lungs? Come on, this sort of checking is an essential part of real-world calculation. --Trovatore (talk) 21:12, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- I wouldn't want to be a short female couch-potato smoker who lives near the Dead Sea -- MacAddct 1984 (talk • contribs) 02:07, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

Antisocial personality Disorder[edit]

What are the effects of Antisocial Personality Disorder? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 192.30.202.18 (talk) 19:24, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

Interesting question. I don't know too much about it, but you can check out the "Symptoms" section in our article on Anitsocial Personality Disorder. --JDitto (talk) 20:05, 20 December 2007 (UTC) (I fixed your link MacAddct 1984 (talk • contribs))

- It's not what most laypeople think it means. Often, people will say "I'm going to be antisocial tonight and just stay home alone". However, this is not how ASPD presents itself at all. A more correct phrase would be, "I'm going to be antisocial tonight and hit mailboxes with a baseball bat". Basically it's doing things that society (or the law) would normally deem inappropriate or malicious. -- MacAddct 1984 (talk • contribs) 20:52, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- If it is the case, please be careful with self-diagnosis. You could have many or even all of these traits and not have Antisocial Personality Disorder. If you are unsure, or feel that any of these apply to you consult a professional who can test your personality using, for example, the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory. (For instance, I have taken this test and although I display some symptoms of Antisocial Personality Disorder, I don't have any antisocial personality disorder). If not - keep on trucking. Lanfear's Bane | t 21:34, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

2 tubules 1 glomerulus[edit]

Is is possible, in a normal kidney, to have more than one tubule originating from a single glomerulus? Although it seems from most textbook cartoons that each single glomerulus connects to exactly one tubule, and vice versa, I have not actually seen any documentation which suggests that this is the only possible configuration. A pathologist and a nephrologist in my hospital have been unable to give me an absolute answer on this. I am most interested to know if this happens in the normal kidney in humans, but would also welcome any relevant information from pathologic or non-human cases. (Just to narrow it down, I am aware of collecting duct anatomy, and am only interested in the connection between the proximal tubular lumen and the glomerular urinary space.) Tuckerekcut (talk) 19:25, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

The opinion below was posted on my talk page. I am copying it here in case anyone is interested in the discussion. Tuckerekcut (talk) 19:22, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

Well,I was going to answer on ref. desk but now i've stuck here.This thing[1],i.e 2 tubules and 1 glomerulus,no way ,no human has been hiding this miracle inside of his mysterious body uptill today ,however i am answerless that what will be happening tomarrow.The thing you are talking about,is just kidney concerns ultimately leading to nephron,having only one glomerulus;the site where pressure filtration occurs then the proximal tubule,loop of henle, distal tubule and eventually the collecting duct. And if i haven't made out the right sense of your question.You can ask me on my talk page,probably my knowledge might be of some use to you.--Mike robert (talk) 18:18, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

- To say that something is not possible, in biology, is a pretty strong statement. As a general rule, however, the nephron is a unit. I'm not aware of any anatomical studies that might answer your question, googling and a pubmed search gave no obvious hits. To pursue this further, I'd suggest reading up on the embryology of the kidney. I'd also suspect that the answer might be species-dependent. --NorwegianBlue talk 22:19, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

Running house lights from a 12 volt battery[edit]

Greetings Wikipedians from a long time lurker on the refdesk!

I have a quick question for those more enlightened in the dark arts of electricity than myself: My father is, given the current rolling power cuts in our country, planning on converting more of our house lights to 12v downlights. He would like to know if he can run them off of a 12v battery in the event of power cuts? His plan is to have one or more batteries connected to some sort of charger connected to the mains, with the other side connected to one or more downlights, so that in the event of a power cut, the battery will continue to power the lights for at least a couple of hours. Each downlight is 50w, although smaller ones are available.

Is there some sort of formula for working out how many chargers / batteries are required? What would be the best way to approach this? Bear in mind that here we use 220v mains. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 196.209.27.242 (talk) 19:31, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- We're going to need some information first:

- Are these lights AC or DC? If AC then they may not like being run from a battery (which is DC).

- How many of them are there?

- Are they wired in parallel or in series (as Xmas tree lights are). You can put twenty 12v bulbs in series and run them off 220v mains current - which saves on fancy transformers and stuff - some fittings may go that route - but you couldn't power them from a car battery anymore! You need them to be wired in parallel - which means that they'll have come with a mains transformer of some kind to step down the wall voltage to 12v - and possibly to convert AC to DC.

- Also - it's important to note that car batteries can be damaged by repeatedly running them flat - that ought not to be a problem - but beware of it. You might want to consider 'Deep Cycle' batteries - of the kind you'd use to power a golf cart or something. However, car batteries are cheaper - and you may not need to run them often enough to care.

- OK - so 1 Watt is one Amp at one Volt. So a 50W, 12V DC lamp requires 50/12 = 4.17 Amps per bulb. A car battery's total capacity varies depending on what you pay for them and how big they are - anywhere between 45 Amp-hours to 150 Amp-hours seems typical. That should run one bulb for between 10 hours to a day or so - or 24 bulbs for half an hour up to a couple of hours. However, there is a general rule for car batteries that you shouldn't attempt to discharge them in under 10 hours - which is probably what you want for a bad power cut. So a puny 45 A.hr battery is really only good for powering one lamp. A big truck battery could maybe run several for that long.

- SteveBaker (talk) 20:23, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- (after ec) I'll cut out the rest of my response to note that, given the AC/DC thing, it may be simpler to consider having a small generator that can be connected rather than using batteries. — Lomn 20:26, 20 December 2007 (UTC)

- Companies like APC make uninterruptible power supplies for computers. A $200 system can generation something like 400 W for an hour. You might look into adapting one of their products, or something similar, for this application. Dragons flight (talk) 00:10, 21 December 2007 (UTC)

- What struck me when I saw Steve's figure of 4+ amps for a single light is that this has implications for the wiring required. Here in North America, the household wiring in a regular lighting circuit is rated for 15 amps. At 12 volts that would only let you run three 50 W lamps! I don't know anything about wiring in South Africa but I imagine the wire gauge is similar. So if you're planning to convert a number of lights, you may have to run heavier wiring between them. Of course, you have quite possibly realized this already.