User:Tommaisey/Renaissance draft

This draft is now outdated. The real article is much improved from this.

| Renaissance |

|---|

|

| Aspects |

| Regions |

| History and study |

The word Renaissance (French for 'rebirth', or Rinascimento in Italian), was first used to define the cultural movement in Italy (and in Europe in general) that began in the late Middle Ages, and spanned roughly the 14th through the 17th century. The principal features were the revival of learning based on classical sources, the rise of courtly and papal patronage, the development of perspective in painting, and the advancements of science. The word Renaissance is now often used to describe other historical and cultural moments (e.g. the Carolingian Renaissance, the Byzantine Renaissance).

Overview[edit]

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that affected much of European intellectual life in the early modern period. Beginning in Italy, and spreading to all of Europe by the 16th century, its influence was felt in literature, philosophy, art, politics, science, religion, and many more aspects of intellectual enquiry. One of its clearest features was the employment of the humanist method in study, and the search for realism and human emotion in art.

Renaissance thinkers focused greatly on seeking out and learning from ancient texts, typically written in Latin or ancient Greek. Scholars scoured Europe's monastic libraries, searching for works of antiquity which had fallen into obscurity. In such texts they found a desire to improve and perfect the worldly, an entirely different sentiment to the transcendental spirituality stressed by medieval Christianity. This is not to say they rejected Christianity; quite the contrary, many of the Renaissance's greatest works were devoted to it, and the Church patronised many works of Renaissance art. However, a subtle shift took place in the way that intellectuals approached religion that was reflected in many other areas of cultural life.

Artists such as Albrecht Dürer strove to portray the human form realisically, developing techniques to render perspective and light more naturally. Political philosophers, most famously Niccolò Machiavelli, sought to describe political life as it really was, and to improve government on the basis of reason. In addition to studying classical Latin and Greek, authors also began increasingly to use vernacular languages; combined with the invention of printing, this would allow many more people access to books, especially the Bible.

In all, the Renaissance could be viewed as an attempt by intellectuals to study and improve the secular and worldly, both through the revival of ideas from antiquity, and through novel approaches to thought.

Origins of the Renaissance[edit]

Most historians agree that the ideas that characterized the Renaissance had their origin in late 13th century Florence, in particular with the writings of Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) and Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374), as well as the painting of Giotto di Bondone (1267-1337).[1] Yet it remains unsure why the Renaissance began in Italy, and why it began when it did. Accordingly, several theories have been put forward to explain its origins.

Assimilation of Greek and Arabic knowledge[edit]

The Renaissance was so called because it was a "rebirth" of certain classical ideas that had long been lost to Europe. It has been argued that the fuel for this rebirth was the rediscovery of ancient texts that had been lost to Western civilisation, but were preserved in some monastic libraries, as well as the Islamic world.[2] Renaissance scholars such as Niccolò de' Niccoli and Poggio Bracciolini scoured the libraries of Europe in search of works by such classical authors as Plato, Cicero and Vitruvius.[3] Additionally, as the reconquest of the Iberian peninsula from Islamic Moors progressed, numerous ancient Greek works were captured from educational institutions such as the library at Córdoba, which claimed to have 400,000 books.[4] Along with these, the works of Arabic scholars (e.g. Averroes), were imported into the Christian world, providing new intellectual material for European scholars.

Greek and Arabic knowledge were not only assimilated from Spain, but also from the Middle East itself. Some knowledge of mathematics, which was flourishing in the Middle East, was brought back by crusaders in the 13th century.[5] The decline of the Byzantine Empire after 1204 - and its eventual fall in 1453 - led to an exodus of Greco-Roman scholars to the West. These scholars brought with them texts and knowledge of the classical Greek and Roman civilizations which had been lost for centuries in the West.[6]

Social and political structures in Italy[edit]

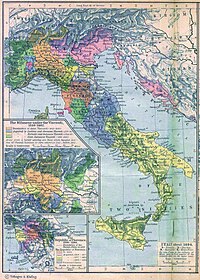

The political structures of late Middle Ages Italy were somewhat unique, leading some to theorize that it was the unusual social climate that allowed the emergence of a rare cultural efflorescence. Italy as a political entity did not exist in the early modern period. Instead, it was divided into smaller city states and territories: the kingdom of Naples controlled the south, the Republic of Florence and the Papal states the centre, the Genoese and the Milanese the north and west, and the Venetians the east. Italy was, in the fifteenth century, one of the most urbanised areas in Europe.[7] Many of its cities stood among the ruins of ancient Roman buildings; it seems likely that the classical nature of the Renaissance was linked to its origin in the Roman Empire's heartlands.[8]

Italy at this time was notable for its Republics, including the Republic of Florence and the Republic of Venice. Although in practice these were oligarchical, and bore little resemblance to a modern democracy, the relative political freedom they afforded was conducive to academic and artistic advancement.[9] Likewise, the position of Italian cities such as Venice as great trading centres made them intellectual crossroads. Merchants brought with them ideas from far corners of the globe, particularly the Levant. Venice was Europe's gateway to trade with the East, and a producer of fine glass, while Florence was a capital of silk and jewelry. The wealth such business brought to Italy meant that large artistic projects could be commissioned, both public and private, and individuals had more leisure time for study.[9]

The Black Death[edit]

One theory is that the devastation caused by the Black Death in Florence (and elsewhere in Europe) resulted in a shift in the world view of people in 14th century Italy. Italy was particularly badly hit by the plague, and it has been speculated that the familiarity with death that this brought caused thinkers to dwell more on their lives on Earth, rather than on spirituality and the afterlife.[10] It has also been argued that the Black Death prompted a new wave of piety, manifested in the sponsorship of religious works of art.[11] However, this notion does not fully explain why the Renaissance occured specifically in Italy in the 14th century. The Black Death was a pandemic that affected all of Europe in the ways described, not only Italy. In all likelihood, the reasons for the Renaissance's emergence in Italy were a complex concatenation of all the factors mentioned above; to highlight just one would be to inappropriately simplify such an unprecedented cultural phenomenon.

Cultural conditions in Florence[edit]

It has long been a matter of debate why the Renaissance began in Florence, and not elsewhere in Italy. Scholars have noted several features unique to Florentine cultural life that may have precipitated such a cultural movement. Many have emphasised the role played by the Medici family in patronising and stimulating the arts. Especially under Lorenzo de' Medici, huge sums were devoted to commissioning works from Florence's leading artists, including Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli, and Michelangelo Buonarroti.[3]

Yet it must be noted that the Renaissance was certainly already underway before Lorenzo came to power; indeed, before the Medici family itself has achieved hegemony in Florentine society. Other historians have postulated that Florence was the birthplace of the Renaissance as a result of luck - in other words, because "Great Men" were born there by chance.[12] Da Vinci, Botticelli and Michelangelo were all born in Tuscany - seemingly as a reuslt of chance. But such chance seems improbable; other historians have contended that these "Great Men" were only able to rise to prominence because of the prevailing cultural conditions at the time.

Characteristics of the Renaissance[edit]

Humanism[edit]

Humanism was not a distinct philosophy, but rather a method of learning. In contrast to the medieval scholastic mode, which focused on resolving contradictions between authors, humanists would study ancient texts in the original, and appraise them through a combination of reasoning and emperical evidence. Humanist education was based on the study of poetry, grammar, ethics and rhetoric. Above all, humanists asserted "the genius of man... the unique and extraordinary ability of the human mind."[13]

Humanist scholars shaped the intellectual landscape throughout the early modern period. Political philosophers such as Niccolò Machiavelli and Thomas More revived the ideas of Greek and Roman thinkers, and applied them in critiques of contemporary government. Theologians, notably Erasmus and Luther, challenged the Aristotlian status quo, introducing radical new ideas of justification and faith (for more, see Religion below).

Art[edit]

One of Renaissance art's distinguishing features was its development of highly realistic linear perspective. Giotto di Bondone (1267-1337) is credited with first treating the canvas as a window into space, but it was not until the work of Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) and Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) that perspective was formalised as an artistic technique.[14] The development of perspective was part of a wider trend towards realism in the arts (for more, see Renaissance Classicism).[15] To that end, painters also developed other techniques, studying light, shadow, and, famously in the case of Leonardo da Vinci, human anatomy. Overarching these changes in artistic method was a renewed desire to depict the beauty of nature, and to unravel the axioms of aesthetics.

By the late 15th century, these artistic ideas were spreading into Northern Europe, where they developed and changed. In the Netherlands, a particularly vibrant scene developed, with artists such as Joachim Patinir and Pieter Aertsen fusing the new techniques with local religious iconography (for more, see Renaissance in the Netherlands). Later, the work of Pieter Brueghel the Elder would inspire artists to depict themes of everyday life.[16]

In architecture, Renaissance ideas of aesthetics were fused with the flourishing discipline of mathematics. Architects such as Filippo Brunelleschi used rediscovered knowledge from Vitruvius and others to build in the classical style, as well as to achieve feats of engineering not previously possible - Brunelleschi's dome on the Duomo of Florence being the most famous example.[17]

Science[edit]

The upheavals occuring in the arts and humanities were mirrored by a highly dynamic period of change in the sciences. Some have chosen to see this flurry of activity as a "scientific revolution," heralding the beginning of the modern age.[18] Others have seen it merely as an acceleration of a continuous process stretching from the ancient world to the present day.[19] Regardless of position on this point, there is general agreement that the Renaissance saw many significant changes in the way the universe was viewed and the methods with which philosphers sought to explain natural phenomena.

During the early Renaissance, science and art were very much intermingled, with artists such as Leonardo da Vinci making observational drawings of anatomy and nature. Yet the most significant development of the era was not a specific discovery, but rather a process for discovery: the scientific method. This revolutionary new way of learning about the world focused on empirical evidence, the importance of mathematics, and discarding the Aristotlian "final cause" in favour of a mechanical philosophy. Early and influential proponents of these ideas included Copernicus and Galileo. While both were later hailed as thinkers of seminal importance, they attracted much contemporary controversy, particularly from the Roman Catholic Church.

In addition to astronomy and physics, the new discipline of scientific method also made great contributions to the fields of biology and anatomy. With the publication of Vesalius's De humani corporis fabrica, a new confidence was placed in the role of dissection, observation, and a mechanistic view of anatomy.

Religion[edit]

It should be emphasised that the new ideals of humanism, although more secular in some aspects, developed against an unquestioned Christian backdrop. Indeed, much (if not most) of the new art was comissioned by or in dedication to the Church. However, the Renaissance had a profound effect on contemporary Theology, particularly in the way people perceived the relationship between man and God. Many of the period's foremost Theologians were followers of the humanist method, including Erasmus, Zwingli, Thomas More, and Luther. Humanism and the Renaissance therefore played a direct role in sparking the Reformation, as well as in many other contemporaneous religious debates and conflicts.

Renaissance self-awareness[edit]

By the fifteenth century, writers, artists and architects in Italy were well aware of the transformations that were taking place and were using phrases like modi antichi (in the antique manner) or alle romana et alla antica (in the manner of the Romans and the ancients) to describe their work. As to the term “rebirth,” it seems that Albrecht Dürer in 1523 was the first to use such a term when he used Wiedererwachung (English: reawakening) to describe Italian art.[20] The term "la rinascita" first appeared, however, in its broad sense in Giorgio Vasari's Vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori Italiani (The Lives of the Artists, 1550-68).[21] Vasari divides the age into three phases: the first phase contains Cimabue, Giotto and Arnolfo di Cambio; the second phase contains Masaccio, Brunelleschi and Donatello; the third centers on Leonardo da Vinci, culminating with Michelangelo. It was not just the growing awareness of classical antiquity that drove this development, according to Vasari, but also the growing desire to study and imitate nature.[22]

The Renaissance Spreads[edit]

From its birthplace of Florence, the Renaissance spread in the 15th century first to the rest of Italy, and soon all over Europe with great speed. The invention of the priniting press was the catalyst which allowed the rapid transmission of these new ideas. As it spread, its ideas diversified and changed, being adapted to local culture as they went. In the twentieth century, scholars began to break the Renaissance into regional and national movements, including:

- The Italian Renaissance

- The English Renaissance

- The German Renaissance

- The Northern Renaissance

- The French Renaissance

- The Renaissance in the Netherlands

- The Polish Renaissance

- The Spanish Renaissance

- Renaissance architecture in Eastern Europe

The Northern Renaissance[edit]

The Renaissance as it occured in Northern Europe has been termed the "Northern Renaissance". It arrived first in France, imported by King Charles VIII after his invasion of Italy. Francis I imported Italian art and artists, including Leonardo Da Vinci, and at great expense built ornate palaces. Writers such as François Rabelais, Pierre de Ronsard, Joachim du Bellay and Michel de Montaigne, painters such as Jean Clouet and musicians such as Jean Mouton also borrowed from the spirit of the Italian Renaissance.

In the second half of the 15th century, Italians brought the new style to Poland and Hungary. After the marriage in 1476 of Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary, to Beatrix of Naples, Buda became the one of the most important artistic centres of the Renaissance north of the Alps.[23] The most important humanists living in Matthias' court were Antonio Bonfini and Janus Pannonius.[23] In 1526 the Ottoman conquest of Hungary put an abrupt end to the short-lived Hungarian Renaissance.

An early Italian humanist who came to Poland in the mid-15th century was Filip Callimachus. Many Italian artists came to Poland with Bona Sforza of Milano, when she married King Zygmunt I of Poland in 1518.[24] This was supported by (at least temporarily) strengthened monarchies in both areas, as well as by newly-established universities.[25]

The spirit of the age spread from France to the Low Countries and Germany, and finally by the late 16th century to England, Scandinavia, and remaining parts of Central Europe (having already earlier reached Hungary and Poland). In these areas humanism became closely linked to the turmoil of the Protestant Reformation, and the art and writing of the German Renaissance frequently reflected this dispute.

In England, the Elizabethan era marked the beginning of the English Renaissance. It saw writers such as William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, John Milton, and Edmund Spenser, as well as great artists, architects (such as Inigo Jones) and composers such as Thomas Tallis, John Taverner, and William Byrd.

The Renaissance arrived in the Iberian peninsula through the Mediterranean possessions of the Aragonese Crown and the city of Valencia. Early Iberian Renaissance writers include Ausiàs March, Joanot Martorell, Fernando de Rojas, Juan del Encina, Garcilaso de la Vega, Gil Vicente and Bernardim Ribeiro. Late Renaissance in Spain saw writers such as Miguel de Cervantes, Lope de Vega, Luis de Góngora and Tirso de Molina, artists such as El Greco and composers such as Tomás Luis de Victoria. In Portugal writers such as Sá de Miranda and Luís de Camões and artists such as Nuno Gonçalves appeared.

While Renaissance ideas were moving north from Italy, there was a simultaneous spread southward of innovation, particularly in music.[26] The music of the 15th century Burgundian School defined the beginning of the Renaissance in that art; and the polyphony of the Netherlanders, as it moved with the musicians themselves into Italy, formed the core of what was the first true international style in music since the standardization of Gregorian Chant in the 9th century.[26] The culmination of the Netherlandish school was in the music of the Italian composer, Palestrina. At the end of the 16th century Italy again became a center of musical innovation, with the development of the polychoral style of the Venetian School, which spread northward into Germany around 1600.

The paintings of the Italian Renaissance differed from those of the Northern Renaissance in some ways. Italian Renaissance artists were among the first to paint secular scenes, breaking away from the purely religious art of medieval painters. At first, Northern Renaissance artists remained focused on religious subjects, such as the contemporary religious upheaval portrayed by Albrecht Dürer. Later on, the works of Pieter Bruegel influenced artists to paint scenes of daily life rather than religious or classical themes. It was also during the northern Renaissance that Flemish brothers Hubert and Jan van Eyck perfected the oil painting technique, which enabled artists to produce strong colors and a hard surface that could survive for centuries.[27]

Historiography of the Renaissance[edit]

The Renaissance as a historical age[edit]

It was not until the nineteenth century that the French word renaissance achieved popularity in describing the cultural movement that began in the late 13th century. The Renaissance was first defined by French historian Jules Michelet (1798-1874), in his 1855 work, Histoire de France. For Michelet, the Renaissance was less a development in art and culture as in science. He asserted that it spanned the period from Columbus to Copernicus to Galileo; that is, from the end of the fifteenth century to the middle of the seventeenth century.[28] The Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt, (1818-1897) in his Die Kultur der Renaissance in Italien,[29] by contrast, defined the Renaissance as the period between the Italian painters Giotto and Michelangelo. His book was widely read and influential in the development of the modern interpretation of the Italian Renaissance.[30] However, Buckhardt has been accused of setting forth a linear Whiggish view of history, seeing the Renaissance as the origin of the modern world.[31]

More recently, historians have been much less keen to define the Renaissance as a historical age, or even a coherent cultural movement. As Randolph Starn has put it,

| “ | Rather than a period with definitive beginnings and endings and consistent content in between, the Renaissance can be (and occasionally has been) seen as a movement of practices and ideas to which specific groups and identifiable persons variously responded in different times and places. It would be in this sense a network of diverse, sometimes converging, sometimes conflicting cultures, not a single, time-bound culture. | ” |

| — Randolph Starn[31] | ||

For Better or For Worse?[edit]

Many historians now view the Italian Renaissance as more of an intellectual and ideological change than a substantive one. Some marxist historians, for example, hold the view that the changes in art, literature, and philosophy were part of a general trend away from feudalism towards capitalism, resulting in a bourgeois class who had leisure time to devote to the arts.[32]

Many historians now point out that most of the negative social factors popularly associated with the "medieval" period - poverty, ignorance, warfare, religious and political persecution, and so forth - seem to have actually worsened in this era which saw the rise of Machiavelli, the Wars of Religion, the corrupt Borgia Popes, and the intensified witch-hunts of the 16th century. Many people who lived during the Renaissance did not view it as the "golden age" imagined by certain 19th century authors, but were concerned by these social maladies.[33] Significantly, though, the artists, writers, and patrons involved in the cultural movements in question believed they were living in a new era that was a clean break from the Middle Ages.[21]

Johan Huizinga (1872–1945) acknowledged the existence of the Renaissance but questioned whether it was a positive change. In his book The Waning of the Middle Ages, he argued that the Renaissance was a period of decline from the High Middle Ages, destroying much that was important. The Latin language, for instance, had evolved greatly from the classical period and was still a living language used in the church and elsewhere. The Renaissance obsession with classical purity halted its natural evolution and saw Latin revert to its classical form. Robert S. Lopez has contended that it was a period of deep economic recession. Meanwhile George Sarton and Lynn Thorndike have both argued that scientific progress was slowed.

Historians have begun to consider the word Renaissance as unnecessarily loaded, implying an unambiguously positive rebirth from the supposedly more primitive "Dark Ages" (Middle Ages). Many historians now prefer to use the term "Early Modern" for this period, a more neutral term that highlights the period as a transitional one that led to the modern world.

Other Renaissances[edit]

The term Renaissance has also been used to define time periods outside of the 15th and 16th centuries. Charles H. Haskins (1870–1937), for example, made a convincing case for a Renaissance of the 12th century.[34] Other historians have argued for a Carolingian Renaissance in the eighth and ninth centuries, and still later for an Ottonian Renaissance in the tenth century.[35] Other periods of cultural rebirth have also been termed "renaissances", such as the Bengal Renaissance or the Harlem Renaissance.

References and Sources[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ See below, under "Sources".

- ^ Hugh Bibbs, The Islamic Foundation of the Renaissance, (Northwest and Pacific, 1999)

- ^ a b Strathern, Paul The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance (2003) p81-90, p172-197

- ^ The Islamic World to 1600, University of Calgary Website

- ^ History of Medieval Mathematics University of South Australia Website

- ^ History of the Renaissance, HistoryWorld

- ^ Julius Kirshner, "Family and Marriage: A socio-legal perspective" Italy in the Age of the Renaissance: 1300-1550, ed. John M. Najemy (Oxford University Press, 2004) p.89

- ^ Jacob Burckhardt, "The Revivial of Antiquity," The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (trans. by S.G.C. Middlemore, 1878)

- ^ a b Jacob Burckhardt, "The Republics: Venice and Florence," The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (trans. by S.G.C. Middlemore, 1878)

- ^ For more, see Barbara Tuchman's book, A Distant Mirror

- ^ The End of Europe's Middle Ages: The Black Death University of Calgary website. Retrieved on 05-04-2007

- ^ Jacob Burckhardt, "The Development of the Individual," The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (trans. by S.G.C. Middlemore, 1878)

- ^ As asserted by Gianozzo Manetti in On the Dignity and Excellence of Man. Cited in Clare, J, Italian Renaissance.

- ^ John D. Clare & Dr. Alan Millen, Italian Renaissance (London, 1994) p14

- ^ David G. Stork, Optics and Realism in Renaissance Art

- ^ Peter Brueghel Biography, Web Gallery of Art

- ^ Richard Hooker, Architecture and Public Space

- ^ Herbert Butterfield, The Origins of Modern Science, 1300-1800, p. viii

- ^ Steven Shapin, The Scientific Revolution, (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Pr., 1996), p. 1.

- ^ Famous Travellers of Italy: Albrecht Dürer Tiscali.de

- ^ a b Erwin Panofsky, Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art, (New York: Harper and Row, 1960)

- ^ Philip Sohm, Style in the Art Theory of Early Modern Italy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001)

- ^ a b Lóránt Czigány, A History of Hungarian Literature, "The Renaissance in Hungary"

- ^ History of Poland on Polish Government's website. Retrieved on 05-04-2007.

- ^ For example, the re-establishment of Jagiellonian University in 1400.

- ^ a b Paul Henry Láng, "The So Called Netherlands Schools," The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 1. (Jan., 1939), pp. 48-59.

- ^ Painting in Oil in the Low Countries and Its Spread to Southern Europe, Metropolitan Museum of Art website. Retrieved 05-04-2007.

- ^ Jules Michelet, History of France, trans. G. H. Smith (New York: D. Appleton, 1847)

- ^ Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (trans. S.G.C Middlemore, London, 1878)

- ^ Peter Gay, Style in History. (New York: Basic Books 1974).

- ^ a b Randolph Starn, "Renaissance Redux" The American Historical Review Vol.103 No.1 p.124

- ^ Renaissance Forum at Hull University, Autumn 1997

- ^ Savonarola's popularity is a prime example of the manifestation of such concerns. Other examples include Phillip II of Spain's censorship of Florentine paintings, noted by Edward L. Goldberg, "Spanish Values and Tuscan Painting", Renaissance Quarterly (1998) p.914

- ^ Charles Homer Haskins. The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1927).

- ^ Jean Hubert. L’Empire Carolingien (English: The Carolingian Renaissance, Translated by James Emmons (New York: G. Braziller, 1970).

Sources[edit]

- Burckhardt, Jacob (1878), The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, trans S.G.C Middlemore, republished in 1990 ISBN 0-14-044534-X

- The Cambridge Modern History. Vol 1: The Renaissance (1902)

- Cronin, Vincent (1967), The Florentine Renaissance, ISBN 0-00-211262-0; (1969), The Flowering of the Renaissance, ISBN 0-7126-9884-1; (1992), The Renaissance, ISBN 0-00-215411-0

- Ergang, Robert (1967), The Renaissance, ISBN 0-442-02319-7

- Ferguson, Wallace K.] (1962), Europe in Transition, 1300-1500, ISBN 0-04-940008-8

- Haskins, Charles Homer (1927), The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century, ISBN 0-674-76075-1

- Huizinga, Johan (1924), The Waning of the Middle Ages, republished in 1990 ISBN 0-14-013702-5

- Jensen, De Lamar (1992), Renaissance Europe, ISBN 0-395-88947-2

- Lopez, Robert S. (1952), Hard Times and Investment in Culture

- Strathern, Paul (2003), The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance, ISBN 1-844-13098-3

- Thorndike, Lynn (1943) 'Renaissance or Prenaissance?' in "Some Remarks on the Question of the Originality of the Renaissance", Journal of the History of Ideas Vol. 4, No. 1, Jan. 1943

- Weiss, Roberto (1969) The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity, ISBN 1-597-40150-1

See also[edit]

Internal Links[edit]

{{Spoken Wikipedia|Renaissance.ogg|2006-21-05}}

- List of Renaissance figures

- Humanism

- Protestant Reformation

- Scientific Revolution

- Renaissance architecture

- Bengal Renaissance

External links[edit]

- Interactive Resources

- Lectures and Galleries

[[Category:Renaissance|*Renaissance]] [[Category:French words and phrases]] [[Category:History of Italy]]