User:Tjo3ya/sandbox

| Grammatical features |

|---|

A predicate is understood in one of two ways.[1]The first views a predicate as everything in a standard declarative sentence except the subject, and the other views a predicate as just the main content verb or associated predicative expression of a sentence. Thus on the first understanding, the predicate of the sentence Frank likes cake is likes cake; on the second understanding, in contrast, the predicate of the same sentence is just the content verb likes, whereby Frank and cake are the arguments of this predicate. Competition between these two ways of understanding predicates can lead to confusion. The first notion of predicates stems from the term logic of antiquity and is prominent in traditional school grammars (traditional grammar), and the second understanding of predicates comes from the more modern predicate logic (or first order logic). Both of these predicate concepts are discussed in this article.

concerns traditional grammar, which tends to view a predicate as one of two main parts of a sentence, the other part being the subject. The purpose of the predicate is to complete an idea about the subject, such as what it does or what it is like. For instance, in a sentence such as Frank likes cake, the subject is Frank and the predicate is likes cake. The second notion of predicates is derived from work in predicate calculus (predicate logic, first order logic) and is dominant in modern theories of syntax and grammar. The predicate is a semantic unit that takes one or more arguments and relates these arguments to each other. On this approach, the predicate in the example sentence Frank likes cake is the verb likes, and the nouns Frank and cake are its arguments.

Both of these predicate concepts, and related notions, are considered in this article.

In traditional grammar[edit]

The predicate in traditional grammar is inspired by propositional logic of antiquity (as opposed to the more modern predicate logic).[a] A predicate is seen as a property that a subject has or is characterized by. A predicate is therefore an expression that can be true of something.[2] Thus, the expression "is moving" is true of anything that is moving. This classical understanding of predicates was adopted more or less directly into Latin and Greek grammars; and from there, it made its way into English grammars, where it is applied directly to the analysis of sentence structure. It is also the understanding of predicates as defined in English-language dictionaries. The predicate is one of the two main parts of a sentence (the other being the subject, which the predicate modifies).[b] The predicate must contain a verb, and the verb requires or permits other elements to complete the predicate, or it precludes them from doing so. These elements are objects (direct, indirect, prepositional), predicatives, and adjuncts:

- She dances. — Verb-only predicate.

- Ben reads the book. — Verb-plus-direct-object predicate.

- Ben's mother, Felicity, gave me a present. — Verb-plus-indirect-object-plus-direct-object predicate.

- She listened to the radio. — Verb-plus-prepositional-object predicate.

- She is in the park. — Verb-plus-predicative-prepositional-phrase predicate.

- She met him in the park. — Verb-plus-direct-object-plus-adjunct predicate.

The predicate provides information about the subject, such as what the subject is, what the subject is doing, or what the subject is like. The relation between a subject and its predicate is sometimes called a nexus. A predicative nominal is a noun phrase, such as in a sentence George III is the king of England, the phrase the king of England being the predicative nominal. The subject and predicative nominal must be connected by a linking verb, also called a copula. A predicative adjective is an adjective, such as in Ivano is attractive, attractive being the predicative adjective. The subject and predicative adjective must also be connected by a copula.

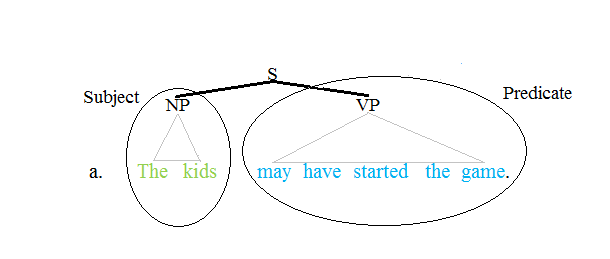

This traditional understanding of predicates has a concrete reflex in many phrase structure theories of syntax. These theories divide an English declarative sentence (S) into a noun phrase (NP) and verb phrase (VP), e.g.[3]

The subject NP is shown in green, and the predicate VP in blue. This concept of sentence structure stands in stark contrast to dependency structure theories of grammar, which place the finite verb (i.e. conjugated verb) as the root of all sentence structure and thus reject this binary NP-VP division, even for English. Languages with more flexible word order (often called nonconfigurational languages) are often treated differently also in phrase structure approaches.

In modern theories of syntax and grammar[edit]

Most modern theories of syntax and grammar take their inspiration for the theory of predicates from predicate logic as associated with Gottlob Frege.[c] This understanding sees predicates as relations or functions over arguments. The predicate serves either to assign a property to a singular term argument or to relate two or more arguments to each other. Sentences consist of predicates and their arguments (and adjuncts) and are thus predicate-argument structures, whereby a given predicate is seen as linking its arguments into a greater structure.[4] This understanding of predicates sometimes renders a predicate and its arguments in the following manner:

- It rains! → rains()

- Bob laughed. → laughed (Bob), or laughed = ƒ(Bob)

- Sam helped you. → helped (Sam, you)

- Jim gave Jill his dog. → gave (Jim, Jill, his dog)

Predicates are placed on the left outside of brackets, whereas the predicate's arguments are placed inside the brackets.[5] One acknowledges the valency of predicates, whereby a given predicate can be avalent (rains in the first sentence), monovalent (laughed in the second sentence), divalent (helped in the third sentence), or trivalent (gave in the fourth sentence). These types of representations are analogous to formal semantic analyses, where one is concerned with the proper account of scope facts of logical quantifiers and logical operators. Concerning basic sentence structure, however, these representations suggest above all that verbs are predicates, and the noun phrases that they appear with their arguments. On this understanding of the sentence, the binary division of the clause into a subject NP and a predicate VP is hardly possible. Instead, the verb is the predicate, and the noun phrases are its arguments.

Other function words (e.g. auxiliary verbs, certain prepositions, phrasal particles, etc.) are viewed as part of the predicate.[6] The matrix predicates are in bold in the following examples:

- Bill will have laughed.

- Will Bill have laughed?

- That is funny.

- Has that been funny?

- They had been satisfied.

- Had they been satisfied, ...

- The butter is in the drawer.

- Fred took a picture of Sue.

- Susan is pulling your leg.

- Whom did Jim give his dog to?

- You should give it up.

Note that not just verbs can be part of the matrix predicate, but also adjectives, nouns, prepositions, etc.[7] The understanding of predicates suggested by these examples sees the main predicate of a clause consisting of at least one verb and a variety of other possible words. The words of the predicate need not form a string nor a constituent,[8] they can be interrupted by their arguments (or adjuncts). The approach to predicates illustrated with these sentences is widespread in Europe, particularly in Germany.[citation needed]

This modern understanding of predicates is compatible with the dependency grammar approach to sentence structure, which places the finite verb as the root of all structure, e.g.[9]

The matrix predicate is (again) marked in blue and its two arguments are in green. While the predicate cannot be construed as a constituent in the formal sense, it is a catena. Barring a discontinuity, predicates and their arguments are always catenae in dependency structures.

Predicators[edit]

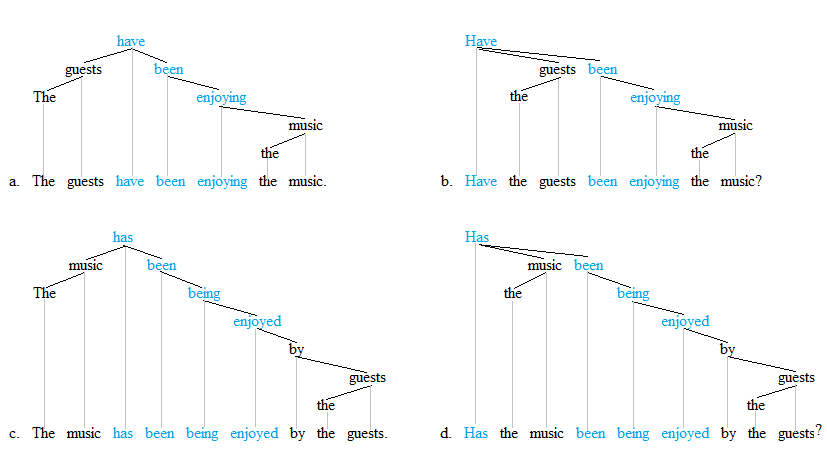

Some theories of grammar seek to avoid the confusion generated by the competition between the two predicate notions by acknowledging predicators.[10] The term predicate is employed in the traditional sense of the binary division of the clause, whereas the term predicator is used to denote the more modern understanding of matrix predicates. On this approach, the periphrastic verb catenae briefly illustrated in the previous section are predicators. Further illustrations are provided next:

The predicators are in blue. These verb catenae generally contain a main verb and potentially one or more auxiliary verbs. The auxiliary verbs help express functional meaning of aspect and voice. Since the auxiliary verbs contribute functional information only, they do not qualify as separate predicators, but rather each time they form the matrix predicator with the main verb.

Carlson classes[edit]

The seminal work of Greg Carlson distinguishes between types of predicates.[11] Based on Carlson's work, predicates have been divided into the following sub-classes, which roughly pertain to how a predicate relates to its subject.

Stage-level predicates[edit]

A stage-level predicate is true of a temporal stage of its subject. For example, if John is "hungry", then he typically will eat some food. His state of being hungry therefore lasts a certain amount of time, and not his entire lifespan. Stage-level predicates can occur in a wide range of grammatical constructions and are probably the most versatile kind of predicate.

Individual-level predicates[edit]

An individual-level predicate is true throughout the existence of an individual. For example, if John is "smart", this is a property that he has, regardless of which particular point in time we consider. Individual-level predicates are more restricted than stage-level ones. Individual-level predicates cannot occur in presentational "there" sentences (a star in front of a sentence indicates that it is odd or ill-formed):

- There are police available. — available is stage-level predicate.

- *There are firemen altruistic. — altruistic is an individual-level predicate.

Stage-level predicates allow modification by manner adverbs and other adverbial modifiers. Individual-level predicates do not, e.g.

- Tyrone spoke French loudly in the corridor. — speak French can be interpreted as a stage-level predicate.

- *Tyrone knew French silently in the corridor. — know French cannot be interpreted as a stage-level predicate.

When an individual-level predicate occurs in past tense, it gives rise to what is called a lifetime effect: The subject must be assumed to be dead or otherwise out of existence.

- John was available. — Stage-level predicate does NOT evoke the lifetime effect.

- John was altruistic. — Individual-level predicate does evoke the lifetime effect.

Kind-level predicates[edit]

A kind-level predicate is true of a kind of thing, but cannot be applied to individual members of the kind. An example of this is the predicate are widespread. One cannot meaningfully say of a particular individual John that he is widespread. One may only say this of kinds, as in

- Cats are widespread.

Certain types of noun phrases cannot be the subject of a kind-level predicate. We have just seen that a proper name cannot be. Singular indefinite noun phrases are also banned from this environment:

- *A cat is widespread. — Compare: Nightmares are widespread.

Collective vs. distributive predicates[edit]

Predicates may also be collective or distributive. Collective predicates require their subjects to be somehow plural, while distributive ones do not. An example of a collective predicate is "formed a line". This predicate can only stand in a nexus with a plural subject:

- The students formed a line. — Collective predicate appears with plural subject.

- *The student formed a line. — Collective predicate cannot appear with singular subject.

Other examples of collective predicates include meet in the woods, surround the house, gather in the hallway and carry the piano together. Note that the last one (carry the piano together) can be made non-collective by removing the word together. Quantifiers differ with respect to whether or not they can be the subject of a collective predicate. For example, quantifiers formed with all the can, while ones formed with every or each cannot.

- All the students formed a line. — Collective predicate possible with all the.

- All the students gathered in the hallway. — Collective predicate possible with all the.

- All the students carried a piano together. — Collective predicate possible with all the.

- *Every student formed a line. — Collective predicate impossible with every.

- *Each student gathered in the hallway. — Collective predicate impossible with each.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Concerning Aristotelian logic as the source for the binary subject-predicate division of the sentence, see Matthews (1981, p. 102).

- ^ See for instance College Dictionary (1993, p. 1077) and Merriam Webster (2004, p. 566).

- ^ There are exceptions to this statement. For instance, Matthews (1981, p. 85), Burton-Roberts (1986, pp. 28+), Thomas (1993, p. 15) and van Riemsdijk & Williams (1986, p. 326) continue to pursue the traditional stance whereby 'predicate' corresponds to the finite VP constituent.

References[edit]

- ^ Most dictionaries of grammar and/or linguistics terminology provide both of the predicate notions discussed in this article. See for instance the Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar or the Oxford Concise Dictionary of Linguistics.

- ^ Kroeger 2005, p. 53.

- ^ Constituency trees like the one here, which divides the sentence into a subject NP and a predicate VP, can be found in most textbooks on syntax and grammar, e.g. Carnie (2007), although the trees of these textbooks will vary in important details.

- ^ For examples of theories that pursue this understanding of predicates, see Langendoen (1970, p. 96+), Cattell (1984), Harrocks (1987, p. 49), McCawley (1988, p. 187), Napoli (1989), Cowper (1992, p. 54), Haegeman (1994, p. 43ff.), Ackerman & Webelhuth (1998, p. 39), Fromkin (2000, p. 117), Carnie (2007, p. 51).

- ^ For examples of this use of notation, see Allerton (1979, p. 259), van Riemsdijk & Williams (1987, p. 241), Bennet (1995, p. 21f).

- ^ See for example Parisi & Antinucci (1976, p. 17+), Brown & Miller (1992, p. 63), Napoli (1989, pp. 14), Napoli (1993, p. 98), Ackerman & Webelhuth (1998, p. 39+). While the analyses of these linguists vary, they agree insofar as various types of function words are grouped together as part of the predicate, which means complex predicates are very possible.

- ^ For examples of theories that extend the predicate to other word classes (beyond verbs), see Cattell (1984), Parisi & Antinucci (1976, p. 34), Napoli (1989, p. 30f), Haegeman (1994, p. 44).

- ^ That many predicates are not constituents is acknowledged by many, e.g. Cattell (1984, p. 50), Napoli (1989, p. 14f).

- ^ Dependency trees like the one here can be found in, for instance, Osborne, Putnam & Groß (2012).

- ^ For examples of grammars that employ the term predicator, see for instance Matthews (1981, p. 101), Huddleston (1988, p. 9), Downing & Locke (1992, p. 48), and Lockwood (2002, p. 4f)

- ^ Carlson (1977a), Carlson (1977b).

Literature[edit]

- Allerton, D (1979). Essentials of grammatical theory. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Ackerman, F.; Webelhuth, G. (1998). A theory of predicates. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

- Burton-Roberts, N (2016). Analysing sentences: An introduction to English Syntax. London: Longman. ISBN 9781317293835.

- The American Heritage College Dictionary (third ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1993.

- Bennet, P. (1995). A course in Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar. London: UCL Press Limited.

- Brown, E.K.; Miller, J.E. (1991). Syntax: A linguistic introduction to sentence structure. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415084215.

- Carlson, G. (1977). A unified analysis of the English bare plural (PDF). Linguistics and Philosophy 1. Vol. 3. pp. 413–58.

- Carlson, G. (1977). Reference to Kinds in English. New York: Garland.

- Also distributed by Indiana University Linguistics Club and GLSA UMass/Amherst.

- Carnie, A. (2007). Syntax: A generative introduction (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Cattell, R. (1984). Composite predicates in English. Syntax and Semantics 17. Sydney: Academic Press.

- Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Cowper, E. (1992). A concise introduction to syntactic theory: The government-binding approach. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Culicover, P. (1997). Principles and Parameters: An introduction to syntactic theory. Oxford University Press.

- Downing, A.; Locke, P. (1992). English grammar: A university course (second ed.). London: Routledge.

- Fromkin, V (2013). Linguistics: An introduction to linguistic theory. Malden, MA: Blackwell. ISBN 9781118670910.

- Haegeman, L. (1994). Introduction to government and binding theory (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Harrocks, G. (1987). Generative Grammar. London: Longman.

- Huddleston, R. (1988). English grammar: An outline. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kroeger, P. (2005). Analyzing Grammar: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139443517.

- Langendoen, T. (1970). The study of syntax: The generative-transformational approach to the study of English. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Lockwood, D. (2002). Syntactic analysis and description: A constructional approach. London: continuum.

- Matthews, P. (1981). Syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McCawley, T. (1988). The syntactic phenomena of English. Vol. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- The Merriam Webster Dictionary. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster. 2004.

- Napoli, D. (1989). Predication theory: A case study for indexing theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Napoli, D. (1993). Syntax: Theory and problems. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Osborne, T.; Putnam, M.; Groß, T. (2012). "Catenae: Introducing a novel unit of syntactic analysis". Syntax. 15 (4): 354–396. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9612.2012.00172.x.

- Oxford Concise dictionary of Linguistics. New York: Oxford University Press. 1997.

- Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar. New York: Oxford University Press. 2014.

- Parisi, D.; Antinucci, F. (1976). Essentials of grammar. Translated by Bates, E. New York: Academic Press.

- van Riemsdijk, H.; Williams, E. (1986). Introduction to the theory of grammar. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Thomas, L. (1993). Beginning syntax. Oxford: Blackwell.

External links[edit]

The dictionary definition of tjo3ya/sandbox at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of tjo3ya/sandbox at Wiktionary

Category:Grammar

Category:Parts of speech

Category:Semantics

- Hello Botterweg, The current version does not do justice to the confusion concerning how the term predicate is understood and used in the relevant areas. Here is how the notion is defined and explained by Matthews (1997:291) in the Oxford Concise Dictionary of Linguistics:

- "predicate: 1. A part of a clause or sentence traditionally seen as representing what is said of, or predicated of, the subject. E.G. in My wife bought a coat in London, the subject my wife refers to someone of whom it is said, in the predicate, that she bought a coat in London. 2. A very or other unit which takes a set of *arguments within a sentence. Thus, in the same example, buy is a two-place predicate whose arguments are represented by my wife and a coat.

- The sense are respectively from ancient and from modern logic. For sense (1) cf. verb phrase, but that is sometimes used of a smaller unit with the predicate. For sense (2) cf. *predicator. But that is often used of the specific word in the construction (e.g. bought; moreover it is not used by logicians."

- The introduction in the current version does not clearly establish that there is competition (ancient vs. modern logic) and thus confusion across the two uses of the term. The old version did do this, however. I would like to change the article back, but we should of course seek a compromise. This compromise can occur, I suggest, by including some statements about confusion and competition between the varying notions and by pointing to the competition between ancient and modern logic in the area.