User:Reynolds~enwiki/not decided yet

PHP 2013: Schistosomiasis: Treating for growth[edit]

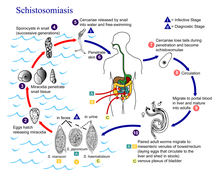

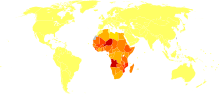

Schistosomiasis has a cross continental distribution with the largest proportion concentrated throughout Africa. It is transmitted through poorly sanitised or contaminated water with snails being an intermediate vector. The development and management of water resources is an important risk factor for schistosomiasis[1] and this disease is associated with developing countries and can result in chronic illness amongst both children and adults. The disease's close association with vital human water resources means that it is extremely difficult to target these snails directly in their natural habitat. Due to this an increase in drug provision as well as a great increase in drug administration and awareness is desperately required.

Epidemiology[edit]

Schistosomiasis, or bilharzia, is a parasitic disease caused by trematode flatworms. Several species of trematodes contribute as a vector for this disease but all come from the genus Schistosoma. The main disease-causing species are S haematobium, S mansoni, and S japonicum. Schistosomiasis is characterised by focal epidemiology and overdispersed population distribution, with higher infection rates in children than in adults. Schistosomiais is prevalent in tropical and sub-tropical areas, especially in poor communities without access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation [2] Acute schistosomiasis, a feverish syndrome, is mostly seen in travellers after primary infection. Chronic schistosomal disease affects mainly individuals with long-standing infections in poor rural areas. Immunopathological reactions against schistosome eggs trapped in the tissues lead to inflammatory and obstructive disease in the urinary system (S haematobium) or intestinal disease, hepatosplenic inflammation, and liver fibrosis (S mansoni, S japonicum) [3] The disease is endemic in 78 countries[4] but only approximately 10% of the infected population currently receive treatment[5] Schistosomiasis particularly affects women who do domestic chores in infected water and the playing habits of children also make them extremely susceptible. mIgration and increasing population size are also introducing the disease to new areas away from the initial lake sites of infection and along with eco tourism are extremely high threats of dispersal. Urogenital schistosomiasis is also considered to be a risk factor for HIV infection, especially in women[6]

Diagnosis and Treatment[edit]

Symptoms of schistosomiasis are caused by the body's reaction to the worms’ eggs, not by the worms themselves. The examination of stool and/or urine for ova is the primary methods of diagnosis for suspected schistosome infections. The choice of sample to diagnose schistosomiasis depends on the species of parasite likely causing the infection. Adult stages of S. mansoni and S. japonicum reside in the mesenteric venous plexus of infected hosts and eggs are shed in faeces. Liver enlargement is common in advanced cases, and is frequently associated with an accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity and hypertension of the abdominal blood vessels. In such cases there may also be enlargement of the spleen For S. haematobium adult worms are found in the venous plexus of the lower urinary tract and eggs are shed in urine. [7]. S. haematobium eggs tend to lodge in the urinary tract causing damage, dysuria and hematuria. Chronic infections may increase the risk of bladder cancer. S. haematobium egg deposition has also been associated with damage to the female genital tract, causing female genital schistosomiasis that can affect the cervix, Fallopian tubes, and vagina and lead to increased susceptibility to other infections [8]. Testing of stool or urine can be of limited sensitivity, particularly for travelers who may have lighter burden infections. To increase the sensitivity of stool and urine examination, three samples should be collected on different days [9]

Praziquantel is the drug treatment of choice. Vaccines are not yet available. Great advances have been made in the control of the disease through population-based chemotherapy but these required political commitment and strong health systems [10] As of 2005, praziquantel is the primary treatment for human schistosomiasis, for which it is usually effective in a single dose.[11] The timing of treatment is important since praziquantel is most effective against the adult worm and requires the presence of a mature antibody response to the parasite. If the pre-treatment stool or urine examination was positive for schistosome eggs, follow up examination at 1 to 2 months post-treatment is suggested to help confirm successful cure [12]

Global burden of disease[edit]

According to WHO, 200 million people are infected worldwide, leading to the loss of 1·53 million disability-adjusted life years[13] Schistosomiasis ranks second only to malaria as the most common parasitic disease, and is the most deadly Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) [14] Throughout the world around 1 billion people are at risk and approximately 300 million are infected[15]. The lack of good sanitation in sub Saharan Africa has been anther major issue when trying to reduce the burden of disease as the snail secondary host makes it hard to reduce transmission. Schistosomiasis is being successfully controlled in many countries but remains a major public health problem but few countries, especially in Africa, have undertaken successful and sustainable control programmes[16] The latest figures suggest that in 2011, around 250 million people were estimated to be infected but only 28.1 million were in fact treated. There are ambiguities in the exact estimated due to a variety of reasons but one example is that Schistosomiasis in travelers often remains unrecognized because doctors are unfamiliar with the clinical presentation and diagnosis of this imported disease. Studies have shown just how robust this disease is with one in particular showing that out of 29 travellers who had swum in freshwater pools in the Dogon area of Mali, West Africa, twenty-eight (97%) of those 29 became infected[17] Increasing population and movement have contributed to increased transmission and introduction of schistosomiasis to new areas[18]

Current funding situation[edit]

The Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI) which is partly funded by the £20 million donation by the Bill & Melinda Gates foundation, has caused an increase in efforts to control the disease using the drug praziquantel. The SCI assists Ministries of Health across sub-Saharan Africa to control and then eliminate schistosomiasis from their population utilising the World Health Organization’s Drug Donation Programme for praziquantel[19] The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has also funded a research program called The Schistosomiasis Consortium for Operational Research and Evaluation or SCORE to answer strategic questions about how to move forward with schistosomiasis control and elimination. SCORE focuses on mass administration of drugs.

Schistosomiasis: Treating for growth[edit]

Background[edit]

Coverage of Schistosomiasis treatment is one of the major failures of present day public health [20] with other neglected tropical diseases such as Onchocerciasis receiving nearly 50% coverage [21] However, a major limitation to schistosomiasis control has been the access to praziquantel and available data show that only 10% of people requiring treatment were reached in 2011. Schistosomiasis control has been successfully implemented in the last 10 years but more can still be done, particularly on the production and distribution side of treatment.

Justification[edit]

Praziquantel has many advantages including its ability to combat the three species of Schistosoma and as well as it being cheap at 8c per dose. From this it would appear that not much needs to be done. However there are still many problems, specifically that of potential drug resistance and distribution to those who really need it. The neglect of this disease has allowed it to become widespread and one of the biggest threats to lives both in Africa and abroad.

Proposal[edit]

Our proposal is to use a combined chemotherapy using artemisinins and praziquantel treatment, which has shown to be effective, [22] to all people in high risk areas in order to combat any ineffectiveness that praziquantel has against immature flukes and resistance. These areas are primarily those clustered around lakes to which Schistosomiasis is present. The identification process is also difficult and as a result we propose the identification of freshwater lakes containing secondary snail hosts as a measure and starting point for our blanket chemotherapy treatment. From this we will also embark upon a mapping scheme to which some of our funding will go towards. This is made slightly easier by the fact that all lakes are infected. We will specifically target the risk groups of people, both children and woman. As well as giving this combination of treatments, we will also supply iron tablets as well. The £1 billion will therefore be used in buying the drugs, distributing them, providing mapping data and in educational purposes to teach locals how to administer the drugs themselves and the benefits of taking such a combination.

Goals[edit]

The goals of our proposal are to primarily benefit the local communities to which this disease has extreme effects and this will be done, as mentioned, through increase production of drugs, combination of treatments, increasing distribution to those affected, providing efficient mapping of the disease and providing education to those areas affected Our further goals for this project are:

To map the risk of Schistosomiasis by 2018 -- To reduce transmission by 20% by the year 2025 -- To eliminate Schistosomiasis in Africa by 2050

We believe that these are all extremely reachable goals, and with the £1 billion pounds being distributed as outlined above, we can make extremely positive and substantial gains to combating one of the worlds most important and highly neglected diseases.

References[edit]

- ^ Steinmann, Peter (July 2006). "Schistosomiasis and water resources development: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimates of people at risk". The Lancet. 6 (7): 411–425. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70521-7. PMID 16790382. Retrieved 27/5/2013.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Schistosomiasis". WHO. Retrieved 31/5/2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Gryseels, Bruno (23-29). "Human schistosomiasis". The Lancet. 368 (9541): 1106–1118. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3. PMID 16997665. S2CID 999943. Retrieved 27/5/2013.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=,|date=, and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Schistosomiasis". WHO.

- ^ "Schistosomiasis". WHO.

- ^ "Schistosomiasis". WHO.

- ^ "Resources for Health Professionals". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ^ "Resources for Health Professionals". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ^ "Resources for Health Professionals". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ^ Gryseels, Bruno (23-29). "Human schistosomiasis". The Lancet. 368 (9541): 1106–1118. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3. PMID 16997665. S2CID 999943. Retrieved 27/5/2013.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=,|date=, and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ The Carter Center. "Schistosomiasis Control Program". Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ^ "Resources for Health Professionals". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ^ Gryseels, Bruno (23-29). "Human schistosomiasis". The Lancet. 368 (9541): 1106–1118. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3. PMID 16997665. S2CID 999943. Retrieved 27/5/2013.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=,|date=, and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The Burden of Schistosomiasis". Centres for disease control and prevention.

- ^ Environmental Management, Bilharzia. Jens Rupp 1996-2004. http://www.escargot.ch/personel/schisto.htm

- ^ Chitsulo, L. (23). "The global status of schistosomiasis and its control". Acta Tropica. 77 (1): 41–51. doi:10.1016/S0001-706X(00)00122-4. PMC 5633072. PMID 10996119.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Visser, L.G (20). "Outbreak of schistosomiasis among travelers returning from Mali, West Africa". 2: 280–5.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chitsulo, L. (23). "The global status of schistosomiasis and its control". Acta Tropica. 77 (1): 41–51. doi:10.1016/S0001-706X(00)00122-4. PMC 5633072. PMID 10996119.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Imperial College London. "What we do". SCI. Retrieved 31/5/2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Hotex P. J., Fenwick A. – Schistosomiasis in Africa: An Emerging Tragedy in our new global health decade – PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 3; 485 (2009)

- ^ http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs115/en/index.html

- ^ Zhang Y. et al. – Parasitological impact of two-year preventive chemotherapy on schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in Uganda – BMC Medicine 5; 27 (2007)