User:Marion Leconte/sandbox/Role of women in agriculture

Place of women in agriculture and the rural world. The distribution of roles according to gender in agriculture is a frequent subject of study by sociologists and agricultural economists and historians, because they are important for understanding the social structure of agrarian and even industrial societies. Agriculture provides many employment and livelihood opportunities around the world.[1]

Work on gender studies in agricultural development is important when defining the concept of family farming and to analyze these relationships and these social links.[2]

Yet women from ethnic minorities and rural communities continue to face many obstacles when trying to access new agricultural technologies and services. Sometimes they are not involved in decision-making processes. Most of the time, these obstacles find their origin in discriminatory practices which can strongly influence the independence of women.[3] · [4]

Several organizations such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and independent research have indicated that increasing gender diversity in business decision-making can improve production conditions.[5]

FAO studies show that women's work is often less paid, with sometimes poor rural employment opportunities outside of agriculture and a lack of choice. Certain social norms can prevent women from achieving entrepreneurial status. In countries where livelihoods are scarce, agricultural work can be very arduous, with intensive working conditions, sometimes in conflict situations.[6]

Native american women[edit]

Life in society varies from one tribe to another and from one region to another, but certain perspectives are common such as being a mother and creating a healthy living environment[7]. Women have an important spiritual and social role, because they transmit cultural knowledge, and take care of children and their beloved ones. Sometimes they have the status of healers, although men are more commonly shamans, chiefs and herbalists[8]. Women were often responsible for overseeing a tribe's agricultural systems and were responsible for harvesting and growing vegetables and plants for other members of their community. Tribal women like the Algonquians planted their fields meticulously and in a way that preserved the sustainability of the land for future use. After harvesting a plot of land until the soil lacked nutrients to continue, women were responsible for deciding when and where to clear new fields, allowing used fields to regenerate[9]. Women of Haudenosaunee tribes often controlled food distribution[10].

-

Sewing(Seminole)

-

Weaving from plant fibers (Navajo)

-

Pumpkin harvest (Cheyenne)

-

Basketry (Chumash)

-

Basketry (Apache)

Mexico[edit]

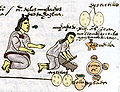

Traditionally, women are responsible for the entire process of making tortillas, from growing the maize to cooking the tortillas to making the flour, it takes a lot of time. To accommodate the modern lifestyle, it is becoming more and more common to purchase bags of tortilla flour or even pre-made tortillas from local markets. This evolution of practices has an impact in rural communities, where the making of tortillas has great importance in traditions and culture. A question that also arises regarding the choice of crops. Genetically modified crops are easier to grow, while women tend to advocate for local maize varieties because it is more nutritional and better tasting[11] · [12].

-

Making tortillas, 1870.

-

Vegetable seller at Guanajuato.

-

Preparation of tortilla in Chiapas.

See also[edit]

Références[edit]

- ^ Khachaturyan, Marianna; Peterson, E. Wesley F. (2018-02-07). "Does Gender Really Matter in Agriculture?" (PDF). Agricultural Economics. Cornhusker Economics, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- ^ Hélène Guétat-Bernard (2014). Féminin-masculin, genre et agricultures familiales (in French). Versailles: Ed. Quae.

- ^ Bernadette P. Resurrección (October 2021). Gender, Climate Change and Disasters: Vulnerabilities, Responses, and Imagining a More Caring and Better World (PDF) (Background Paper for the Expert Group Meeting, Commission on the Status of Women).

- ^ Women's leadership and gender equality in climate action and disaster risk reduction in Africa − A call for action. Accra: FAO & The African Risk Capacity (ARC) Group. 2021. doi:10.4060/cb7431en. ISBN 978-92-5-135234-2.

- ^ Garcia, Alicea Skye; Wanner, Thomas (2017). "Gender inequality and food security: Lessons from the gender-responsive work of the International Food Policy Research Institute and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation". Food Security. 9 (5): 1091–1103. doi:10.1007/s12571-017-0718-7.

- ^ The status of women in agrifood systems - Overview. Rome: FAO. 2023. doi:10.4060/cc5060en.

- ^ Tarrell Awe Agahe Portman (2001). "Debunking the Pocahontas Paradox: The Need for a Humanistic Perspective". The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development. 40.2: 185–99.

- ^ Rayna Green (1992). Women in American Indian society. New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers..

- ^ Wilson, James (1998). The earth shall weep: a history of Native America. New York, NY: Atlantic Monthly Press..

- ^ Evans, Sara Margaret (1997). Born for liberty: a history of women in America. New York, NY: Free Press Paperbacks published by Simon & Schuster..

- ^ Hellin, Jon; Keleman, Alder; Bellon, Mauricio (2010). "Maize diversity and gender: Research from Mexico". Gender & Development. 18 (3): 427–437. doi:10.1080/13552074.2010.521989.

- ^ Bee, Beth A. (2014). ""Si no comemos tortilla, no vivimos:" women, climate change, and food security in central Mexico". Agriculture and Human Values (in Spanish). 31 (4): 607–620. doi:10.1007/s10460-014-9503-9. hdl:10342/12420. S2CID 254228353.