User:InterstellarGamer12321/Sulfur compounds

Common oxidation states of sulfur range from −2 to +6. Sulfur forms stable compounds with all elements except the noble gases.

Allotropes[edit]

Sulfur forms over 30 solid allotropes, more than any other element.[1] Besides S8, several other rings are known.[2] Removing one atom from the crown gives S7, which is more of a deep yellow than the S8. HPLC analysis of "elemental sulfur" reveals an equilibrium mixture of mainly S8, but with S7 and small amounts of S6.[3] Larger rings have been prepared, including S12 and S18.[4][5]

Amorphous or "plastic" sulfur is produced by rapid cooling of molten sulfur—for example, by pouring it into cold water. X-ray crystallography studies show that the amorphous form may have a helical structure with eight atoms per turn. The long coiled polymeric molecules make the brownish substance elastic, and in bulk this form has the feel of crude rubber. This form is metastable at room temperature and gradually reverts to crystalline molecular allotrope, which is no longer elastic. This process happens within a matter of hours to days, but can be rapidly catalyzed.

Electron transfer reactions[edit]

3)

Sulfur polycations, S82+, S42+ and S162+ are produced when sulfur is reacted with oxidising agents in a strongly acidic solution.[6] The colored solutions produced by dissolving sulfur in oleum were first reported as early as 1804 by C.F. Bucholz, but the cause of the color and the structure of the polycations involved was only determined in the late 1960s. S82+ is deep blue, S42+ is yellow and S162+ is red.[7]

Reduction of sulfur gives various polysulfides with the formula Sx2-, many of which have been obtained crystalline form. Illustrative is the production of sodium tetrasulfide:

- 4 Na + S8 → 2 Na2S4

Some of these dianions dissociate to give radical anions, such as S3− gives the blue color of the rock lapis lazuli.

This reaction highlights a distinctive property of sulfur: its ability to catenate (bind to itself by formation of chains). Protonation of these polysulfide anions produces the polysulfanes, H2Sx where x= 2, 3, and 4.[9] Ultimately, reduction of sulfur produces sulfide salts:

- 16 Na + S8 → 8 Na2S

The interconversion of these species is exploited in the sodium–sulfur battery.

Hydrogenation[edit]

Treatment of sulfur with hydrogen gives hydrogen sulfide. When dissolved in water, hydrogen sulfide is mildly acidic:[10]

- H2S ⇌ HS− + H+

Hydrogen sulfide gas and the hydrosulfide anion are extremely toxic to mammals, due to their inhibition of the oxygen-carrying capacity of hemoglobin and certain cytochromes in a manner analogous to cyanide and azide (see below, under precautions).

Combustion[edit]

The two principal sulfur oxides are obtained by burning sulfur:

- S + O2 → SO2 (sulfur dioxide)

- 2 SO2 + O2 → 2 SO3 (sulfur trioxide)

Many other sulfur oxides are observed including the sulfur-rich oxides include sulfur monoxide, disulfur monoxide, disulfur dioxides, and higher oxides containing peroxo groups.

Halogenation[edit]

Sulfur reacts with fluorine to give the highly reactive sulfur tetrafluoride and the highly inert Sulfur hexafluoride.[11] Whereas fluorine gives S(IV) and S(VI) compounds, chlorine gives S(II) and S(I) derivatives. Thus, sulfur dichloride, disulfur dichloride, and higher chlorosulfanes arise from the chlorination of sulfur. Sulfuryl chloride and chlorosulfuric acid are derivatives of sulfuric acid; thionyl chloride (SOCl2) is a common reagent in organic synthesis.[12]

Pseudohalides[edit]

Sulfur oxidizes cyanide and sulfite to give thiocyanate and thiosulfate, respectively.

Metal sulfides[edit]

Sulfur reacts with many metals. Electropositive metals give polysulfide salts. Copper, zinc, silver are attacked by sulfur, see tarnishing. Although many metal sulfides are known, most are prepared by high temperature reactions of the elements.[13]

Organic compounds[edit]

- Illustrative organosulfur compounds

-

Allicin, a chemical compound in garlic

-

(R)-cysteine, an amino acid containing a thiol group

-

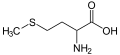

Methionine, an amino acid containing a thioether

-

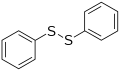

Diphenyl disulfide, a representative disulfide

-

Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid, a surfactant

-

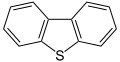

Dibenzothiophene, a component of crude oil

-

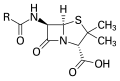

Penicillin, an antibiotic where "R" is the variable group

Some of the main classes of sulfur-containing organic compounds include the following:[14]

- Thiols or mercaptans (so called because they capture mercury as chelators) are the sulfur analogs of alcohols; treatment of thiols with base gives thiolate ions.

- Thioethers are the sulfur analogs of ethers.

- Sulfonium ions have three groups attached to a cationic sulfur center. Dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) is one such compound, important in the marine organic sulfur cycle.

- Sulfoxides and sulfones are thioethers with one and two oxygen atoms attached to the sulfur atom, respectively. The simplest sulfoxide, dimethyl sulfoxide, is a common solvent; a common sulfone is sulfolane.

- Sulfonic acids are used in many detergents.

Compounds with carbon–sulfur multiple bonds are uncommon, an exception being carbon disulfide, a volatile colorless liquid that is structurally similar to carbon dioxide. It is used as a reagent to make the polymer rayon and many organosulfur compounds. Unlike carbon monoxide, carbon monosulfide is stable only as an extremely dilute gas, found between solar systems.[15]

Organosulfur compounds are responsible for some of the unpleasant odors of decaying organic matter. They are widely known as the odorant in domestic natural gas, garlic odor, and skunk spray. Not all organic sulfur compounds smell unpleasant at all concentrations: the sulfur-containing monoterpenoid (grapefruit mercaptan) in small concentrations is the characteristic scent of grapefruit, but has a generic thiol odor at larger concentrations. Sulfur mustard, a potent vesicant, was used in World War I as a disabling agent.[16]

Sulfur–sulfur bonds are a structural component used to stiffen rubber, similar to the disulfide bridges that rigidify proteins (see biological below). In the most common type of industrial "curing" or hardening and strengthening of natural rubber, elemental sulfur is heated with the rubber to the point that chemical reactions form disulfide bridges between isoprene units of the polymer. This process, patented in 1843, made rubber a major industrial product, especially in automobile tires. Because of the heat and sulfur, the process was named vulcanization, after the Roman god of the forge and volcanism.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Steudel, Ralf; Eckert, Bodo (2003). Solid Sulfur Allotropes Sulfur Allotropes. Topics in Current Chemistry. Vol. 230. pp. 1–80. doi:10.1007/b12110. ISBN 978-3-540-40191-9.

- ^ Steudel, R. (1982). "Homocyclic sulfur molecules". Inorganic Ring Systems. Topics in Current Chemistry. Vol. 102. pp. 149–176. doi:10.1007/3-540-11345-2_10. ISBN 978-3-540-11345-4.

- ^ Tebbe, Fred N.; Wasserman, E.; Peet, William G.; Vatvars, Arturs; Hayman, Alan C. (1982). "Composition of Elemental Sulfur in Solution: Equilibrium of S

6, S7, and S8 at Ambient Temperatures". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 104 (18): 4971–4972. doi:10.1021/ja00382a050. - ^ Meyer, Beat (1964). "Solid Allotropes of Sulfur". Chemical Reviews. 64 (4): 429–451. doi:10.1021/cr60230a004.

- ^ Meyer, Beat (1976). "Elemental sulfur". Chemical Reviews. 76 (3): 367–388. doi:10.1021/cr60301a003.

- ^ Shriver, Atkins. Inorganic Chemistry, Fifth Edition. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York, 2010; pp 416

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Greenwoodwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Fujimori, Toshihiko; Morelos-Gómez, Aarón; Zhu, Zhen; Muramatsu, Hiroyuki; Futamura, Ryusuke; Urita, Koki; Terrones, Mauricio; Hayashi, Takuya; Endo, Morinobu; Young Hong, Sang; Chul Choi, Young; Tománek, David; Kaneko, Katsumi (2013). "Conducting linear chains of sulphur inside carbon nanotubes". Nature Communications. 4: 2162. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2162F. doi:10.1038/ncomms3162. PMC 3717502. PMID 23851903.

- ^ Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd ed. Edited by G. Brauer, Academic Press, 1963, NY. Vol. 1. p. 421.

- ^ Greenwood, N. N.; & Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.), Oxford:Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

- ^ Hasek, W. R. (1961). "1,1,1-Trifluoroheptane". Organic Syntheses. 41: 104. doi:10.1002/0471264180.os041.28.

- ^ Rutenberg, M. W.; Horning, E. C. (1950). "1-Methyl-3-ethyloxindole". Organic Syntheses. 30: 62. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.030.0062.

- ^ Vaughan, D. J.; Craig, J. R. "Mineral Chemistry of Metal Sulfides" Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1978) ISBN 0-521-21489-0

- ^ Cremlyn R. J. (1996). An Introduction to Organosulfur Chemistry. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-95512-4.

- ^ Wilson, R. W.; Penzias, A. A.; Wannier, P. G.; Linke, R. A. (15 March 1976). "Isotopic abundances in interstellar carbon monosulfide". Astrophysical Journal. 204: L135–L137. Bibcode:1976ApJ...204L.135W. doi:10.1086/182072.

- ^ Banoub, Joseph (2011). Detection of Biological Agents for the Prevention of Bioterrorism. NATO Science for Peace and Security Series A: Chemistry and Biology. p. 183. Bibcode:2011dbap.book.....B. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-9815-3. ISBN 978-90-481-9815-3. OCLC 697506461.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)