User:FlightoftheArrow/sandbox

Freewill is the philosophical doctrine that the actions of humans are unhindered from certain restraints. Discussions about what types of restraints are important have included restraints of the physical(chains, shackles, jails), of the social(coercion, punishment, rejection) and of the mental(brain injury, psychological disorders.) With so many advances in technology in the contemporary world, and with the resulting leaps in the study of psychology, there has renewed discussion about the implications of free will on ethics. Criminology is a particular field that is affected by the moral responsibility assigned to human actions. A lack of free will raises question as to how crimes should be handled, how to deal with those involved, and of the validity of the humanity of current systems.

Types of free will[edit]

Several different types of are generally discussed in detail. Opinions vary on which types humans exhibit and which types are important for humans to exhibit. This often makes free will a difficult topic to discuss, as many people have different versions of what they believe the concept should include.[1][2]

- Self-realization asserts that humans must be free to act without physical bindings. Shackles, physical disabilities and incarceration strip one of this type of free will. This type of free will, sometimes nicknamed "regular free will," is the kind usually dealt with in the court of law. Judges are primarily concerned with whether a convict had the "choice" to not execute whatever crime he committed. It is concerned mainly with whether the subject was affected by coercion or another type of unfair persuasion when making his decision.[1]

- Self-control stipulates that the possessor to reflect upon their own actions and designate whether they stem from desired or undesired motives.

- Self-perfection stipulates that the possessor to reflect upon their own actions and designate whether they stem from desired or undesired motives and that the desired motives must be morally right. This is the freedom often associated with the Christian God, as he is unable to commit immoral acts(only free to do what is morally correct).

- Self-determination is defined as the ability to act on a will that was fundamentally created by the actor. This is one of the two freedoms that are most associated with the assignment of responsibility to action.

- Self-formation is the power of the actor to alter the will that they themselves were responsible for making. This is the second freedom that is associated with the assignment of responsibility to action.

Determinism[edit]

Determinism is idea that all events have natural causes and adhere to natural laws. Many theories regarding determinism describe events as following a predetermined path. Human action, therefore, is determined and can be predicted prior to actualization with adequate information. The general philosophy today states that humans are a product of their genetic predispositions, their social interactions, and the reactions of their bodies with environmental factors.

Genetic Determinism[edit]

Genetic determinism is a form of determinism that submits heredity and genetic predispositions as being powerful factors in the process of decision making. A recent Florida State University study by members of the College of Criminology and Criminal Justice has revealed information about a particular gene sometimes known as the “warrior gene.” Monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) has been linked with aggression; males who carry it are far more likely to engage in gang activity.[3][4] In past studies it has been discovered to dominate the heredity of warlike cultures (Fairhurst). Enthusiasts of this philosophy argue that if one gene can influence behavior so powerfully, it is likely all actions are to some degree predetermined by uncontrolled ancestry.

Social Determinism[edit]

Social Determinism is philosophy that all human action is determined by the social situation the individual is in. This idea is closely related to psychological behaviorism, in which actions are trained by reward(social acceptance) and punishment(social ostracizing). As the famous behaviorist Ivan Pavlov said, “give me a dozen healthy infants…and [I can] train [them] to become any type of specialist…doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and yes, even beggar-man and thief.”

Defenders of this idea assert that, although a person may be able to “choose” the friends they keep (and other influences that surround them), these decisions are determined by past friends or past hobbies (which were determined by past interactions). For one to truly be responsible for their actions, they must at some point have been responsible for the formation of their current character. Their current character, of course, is defined by decisions they made in the past; if these past decisions were not made freely, their future decisions would also not be free. This assertion is known as “Strawson’s Basic Argument.”[2] The logic follows through endlessly; that is, every past formation of character must have been brought about by a free choice made prior to it, extending back infinitely into the past. Because the life of a human is not infinite, it is concluded that at some point each human must not have been in control of their character, and thus, can never be in control, even in latter instances.

Social determinism is often contrasted with genetic determinism in a psychological debate known as nature versus nurture. This is a long-held debate over which factors influence behavior more: those genetic innate factors or the factors that shape and individual after birth (environment, social interactions). The popular position is a form of equilibrium between the two.

Newtonian Physics Determinism[edit]

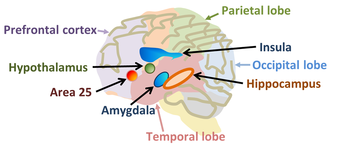

Newtonian physics determinism bases itself on the assumption that the natural world is composed of molecules that act in accordance with the laws of physics and chemistry, and implies that the brain, being part of the world, must adhere to these same laws. It is sometimes known as Nomological determinism. A person is not able to step outside his brain to alter his will by his own design: doing so would be comparable to a computer stepping out of its programming and rewriting its own script. [5] This idea stems further in Laplace's demon[6], the theory that if precise data were known about every molecule in a closed system, then every event that system could be predicted exactly. The closed system is the Universe, and every event on the Earth may be foretold. A popular thought experiment, is the question “If a person were put into the same situation as they were back when they made a certain decision, if all of the molecules of their brain were arranged exactly the way they were when that decision was made, and every environmental influence was acting upon them in identical ways, would they be able to choose differently than what they had already chosen?”[5]

Quantum Physics Determinism[edit]

Many Libertarians argue that the unusual occurrences at the quantum level, which are usually attributed to true randomness, present a sanctuary for free will to exist. Many agree that discoveries in this field present reason to abstain from taking a position on the free will debate until more evidence is uncovered.[7] In fact, some of the leading scientists in psychological field of free will agree that experiments on free will do not disprove its existence in the way determinist enthusiasts declare it does.[1]

Ethics of Determinism[edit]

Alternative Choices[edit]

One of the common premises in the discussions of the effect of determinism on ethics is moral responsibility requires an availability of alternative possibilities. The argument being that if a person is unable to choose differently than one predestined choice, it is not correct to blame that person if their actions are immoral or unlawful.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

One of the most compelling arguments against this premise is called a Frankfurt example. This is a thought experiment that invites one to create a situation in which there is only one choice, yet it appears to the actor as if there are multiple (e.g. there are two doors and only one is unlocked). The actor may freely choose to use the unlocked door, unaware that had he tried the locked door first he would have been forced to take the unlocked one instead. In this situation, it is asserted that the actor may be held morally responsible for choosing the unlocked door, despite that having been his only option.[2]

Criminology in Determinism[edit]

The impact of determinism on criminology pertains to the premise that if one does accept that criminals have no choice but to commit the atrocities they do, it rules out the theory of punishment as a means to gain retribution or implement revenge. [5] There are still several reasons for punishments to be continued.

- Incapacitation(to protect those individuals not inclined to break the law from those that are)

- Deterrence(to affect those individuals inclined to break the law in a discouraging way)

- Reformation(to assimilate criminals back into smoothly flowing society)

It is important to realize that criminals would no more deserve punishment than a carrier of an infectious disease; however, it is still rational to ensure the protection of people lacking criminal disposition by quarantining criminals: much as a diseased patient would be. [2] It follows that society may wish to punish criminals in an attempt to discourage others who are on the brink of transgression. Within a Deterministic point of view, the only separation between a Good Samaritan and a criminal is happenstance. Therefore, it makes sense to do everything possible to help criminals reenter society. Retribution would no longer be included in this list.

If one does accept that criminals have no choice but to commit the atrocities they do, it rules out the theory of punishment as a means to gain retribution or implement revenge.[5] It is useful to note that these types of accommodations are already made to a limited extent; if an accused is found to be suffering from some kind of mental disorder, or if their brain is found to be afflicted by a behavior manipulating tumor, their punishment is often diminished or altered from, perhaps, jail time to a period in a psychiatric hospital.

A deterministic view of the universe may be as bleak and hopeless as some believe it must be by definition. Experiments have shown that when people accept that they have no control over their actions, they become much more aggressive and likely to cheat.[1] For this reason, it is the opinion of some that we should abandon the search for truth, keep a belief in free will, and avoid this problem. However, Determinist believe this would be unfair to the people of society who, by no fault of their own, are criminals. In today’s world, fault heavily falls on the shoulders of criminals.

Extensive studies have affirmed that judges do not treat details such as documented childhood abuse as mitigations in sentences.[3] This is unusual, as traumatic events affect the biological brain in the same ways that mental illnesses do. If biosocial criminology were better understood, perhaps that knowledge would facilitate the arrival of a less bleak world; the idea of determinism is far from hopeless. People in lower social status are looked down upon all over the world; if a deterministic point of view were adopted, it would become clear that these unfortunate individuals must be given help.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d "Does Freewill Exist?" Interview by Austin Allen. Big Think. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Mar. 2013.| [1]

- ^ a b c d Kane, Robert. A Contemporary Introduction to Free Will. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005. Print.

- ^ a b Szalavitz, Maia. "My Brain Made Me Do It: Psychopaths and Free Will." Time.com. Time Inc., 17 Aug. 2012. Web. 21 Feb. 2013.|[2]

- ^ Fairhurst, Libby. "Florida State Study Links 'Warrior Gene' to Gang Membership, Weapon Use." FSU News. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Mar. 2013. |[3]

- ^ a b c d Coyne, Jerry A. "Why You Don't Really Have Free Will." USATODAY.COM. Gannett Company, 1 Jan. 2012. Web. 21 Feb. 2013.|[4]

- ^ Pierre-Simon Laplace, "A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities" (full text).

- ^ McCrone, John. “Nervous Free Will” The Lancet Neurology Volume 2, Issue 1(2003). Page 66. Web. 20 Feb. 2013.|[5]