User:Estevezj/sandbox/microbiome

A microbiome is the totality of microbes, their genetic elements (genomes), and environmental interactions in a particular environment. The term "microbiome" was coined by Joshua Lederberg, who argues that microorganisms inhabiting the human body should be included as part of the human genome, because of their influence on human physiology.[1] The human body contains over 10 times more microbial cells than human cells.[2] A proposal has been made to classify people by enterotype, based on the composition of the gut microbiome. Three human enterotypes have been proposed.[3][4]

Microbiomes are being characterized in many other environments as well, including soil, seawater and freshwater systems.

Etymology[edit]

History[edit]

Symbiosis[edit]

Animals[edit]

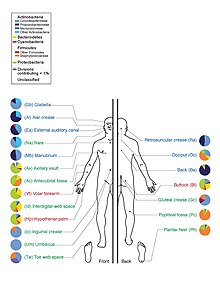

Human microbiome[edit]

- Relationship between microbiota and cancer risk. [5]

Insect-microbe symbioses[edit]

Gastrointestinal[edit]

- Commensal relationships in the human gut are important.[6]

Plants[edit]

Plant microbiomes have been less intensively studied than intestinal microbes but recent work has highlighted the importance of microbial communities in maintaining plant health.[7]

Marine life[edit]

Research methods[edit]

16S rRNA gene sequencing[edit]

Metagenomics[edit]

Metatranscriptomics[edit]

Metaproteomics[edit]

Systems microbiology[edit]

- HGT and microbiome [8]

Applications[edit]

Medicine[edit]

Fecal transplantation[edit]

Biotechnology[edit]

References[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Lederberg, Joshua (2001-04-02). "'Ome Sweet 'Omics–A Genealogical Treasury of Words". The Scientist. Vol. 17, no. 7.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Zimmer, Carl (13 July 2010). "How Microbes Defend and Define Us". New York Times. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (April 20, 2011). "Bacteria Divide People Into 3 Types, Scientists Say". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

a group of scientists now report just three distinct ecosystems in the guts of people they have studied.

- ^ Arumugam, Manimozhiyan; et al. (2011). "Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome". Nature. 473 (7346): 174–80. doi:10.1038/nature09944. PMC 3728647. PMID 21508958.

Our knowledge of species and functional composition of the human gut microbiome is rapidly increasing, but it is still based on very few cohorts and little is known about variation across the world. By combining 22 newly sequenced faecal metagenomes of individuals from four countries with previously published data sets, here we identify three robust clusters (referred to as enterotypes hereafter) that are not nation or continent specific.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ahn, Jiyoung; Chen, Calvin Y.; Hayes, Richard B. (2012-01-22). "Oral microbiome and oral and gastrointestinal cancer risk". Cancer Causes & Control. 23 (3): 399–404. doi:10.1007/s10552-011-9892-7. ISSN 1573-7225 0957-5243, 1573-7225. PMC 3767140. PMID 22271008. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help) - ^ Hooper, L. V.; Gordon, J. I. (2001). "Commensal Host-Bacterial Relationships in the Gut". Science. 292 (5519): 1115–1118. doi:10.1126/science.1058709. PMID 11352068.(subscription required)

- ^ Doornbos, R.F. (2011). "Impact of induced systemic resistance on the bacterial microbiome of Arabidopsis thaliana". IOBC/WPRS Bulletin. 71: 169–172.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Smillie, Chris S.; Smith, Mark B.; Friedman, Jonathan; Cordero, Otto X.; David, Lawrence A.; Alm, Eric J. (2011-12-08). "Ecology drives a global network of gene exchange connecting the human microbiome". Nature. 480 (7376): 241–244. doi:10.1038/nature10571. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 22037308. Retrieved 2012-01-25.