User:Esquivalience/sandbox3

Prevailing bitcoin logo | |

| Unit | |

|---|---|

| Symbol | ₿[b] |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 10−3 | millibitcoin[2] |

| 10−6 | microbitcoin; bit[4] |

| 10−8 | satoshi[5] |

| Symbol | |

| millibitcoin[2] | mBTC |

| microbitcoin; bit[4] | μBTC |

| Coins | Unspent outputs of transactions denominated in any multiple of satoshis[3]: ch. 5 |

| Demographics | |

| Date of introduction | 3 January 2009 |

| User(s) | Worldwide |

| Issuance | |

| Administration | Decentralized[6][7] |

| Valuation | |

| Supply growth | 12.5 bitcoins per block (approximately every ten minutes) until mid 2020,[8] and then afterwards 6.25 bitcoins per block for 4 years until next halving. This halving continues until 2110–40, when 21 million bitcoins will have been issued. |

| |

Bitcoin is a worldwide cryptocurrency and digital payment system[9]: 3 called the first decentralized digital currency, as the system works without a central repository or single administrator.[9]: 1 [10] It was invented by an unknown programmer, or a group of programmers, under the name Satoshi Nakamoto[11] and released as open-source software in 2009.[12] The system is peer-to-peer, and transactions take place between users directly, without an intermediary.[9]: 4 These transactions are verified by network nodes and recorded in a public distributed ledger called a blockchain.

Bitcoins are created as a reward for mining. They can be exchanged for other currencies,[13] products, and services. As of February 2015, over 100,000 merchants and vendors accepted bitcoin as payment.[14] Bitcoin can also be held as an investment. According to research produced by Cambridge University in 2017, there are 2.9 to 5.8 million unique users using a cryptocurrency wallet, most of them using bitcoin.[15]

Terminology[edit]

The word bitcoin occurred in the white paper[16] that defined bitcoin published on 31 October 2008.[17] It is a compound of the words bit and coin.[18] The white paper frequently uses the shorter coin.[16]

There is no uniform convention for bitcoin capitalization. Some sources use Bitcoin, capitalized, to refer to the technology and network and bitcoin, lowercase, to refer to the unit of account.[19] The Wall Street Journal,[20] The Chronicle of Higher Education,[21] and the Oxford English Dictionary[18] advocate use of lowercase bitcoin in all cases, a convention which this article follows.

Units[edit]

The unit of account of the bitcoin system is bitcoin. As of 2014[update], symbols used to represent bitcoin are BTC,[a] XBT,[b] and ₿.[26]: 2 Small amounts of bitcoin used as alternative units are millibitcoin (mBTC),[2] microbitcoin (µBTC, sometimes referred to as bit), and satoshi. Named in homage to bitcoin's creator, a satoshi is the smallest amount within bitcoin representing 0.00000001 bitcoin, one hundred millionth of a bitcoin.[5] A millibitcoin equals to 0.001 bitcoin, one thousandth of a bitcoin.[27] One microbitcoin equals to 0.000001 bitcoin, one millionth of a bitcoin.

Design[edit]

Blockchain[edit]

The blockchain is a public ledger that records bitcoin transactions.[28] A network of communicating nodes running bitcoin software maintain the blockchain.[9] Users can send bitcoin to one or more recipients by broadcasting the transaction to this network using readily available software applications.[29] Network nodes can validate transactions, add them to their copy of the ledger, and then broadcast these ledger additions to other nodes. The blockchain is a distributed database – to achieve independent verification of the chain of ownership of any and every bitcoin amount, each network node stores its own copy of the blockchain.[30]

Approximately six times per hour, a new group of accepted transactions, a block, is created, added to the blockchain, and quickly published to all nodes. This allows bitcoin software to determine when a particular bitcoin amount has been spent, which is necessary in order to prevent double-spending in an environment without central oversight. Whereas a conventional ledger records the transfers of actual bills or promissory notes that exist apart from it, the blockchain is the only place that bitcoins can be said to exist in the form of unspent outputs of transactions.[3]: ch. 5

Ownership[edit]

The blockchain associates an account of bitcoin with a specific address. Bitcoin transactions specify the bitcoin address of the recipient. Every bitcoin address has a corresponding public key and private key. These keys have a special property that a user who can access the private key can digitally sign data—in this case, transactions—which other users can verify using the public key.[3]: ch. 5

A user owns the bitcoins associated to a specific address if the user has access to its corresponding private key. In order to spend bitcoins with a bitcoin transaction, the payer must digitally sign the transaction using the private key. Without knowledge of the private key, the transaction cannot be signed and bitcoins cannot be spent. The network verifies the signature using the public key. If the transaction is valid, it is added to the blockchain.[3]: ch. 5

If the private key is lost, the bitcoin network will not recognize any other evidence of ownership;[9] the coins are then unusable, and effectively lost. For example, in 2013 one user claimed to have lost 7,500 bitcoins, worth $7.5 million at the time, when he accidentally discarded a hard drive containing his private key.[31] A backup of his key(s) would have prevented this.[32]

Transactions[edit]

Transactions consist of one or more inputs and one or more outputs. When a user sends bitcoins, the user designates each address and the amount of bitcoin being sent to that address in an output. Each input refers to unspent coins by specifying previous outputs in the blockchain. To prevent users from spending coins that they do not own, the transaction must carry the digital signature of each input owner.[34] Transactions are defined using a Forth-like scripting language.[3]: ch. 5 The use of multiple inputs corresponds to the use of multiple coins in a cash transaction. Since transactions can have multiple outputs, users can send bitcoins to multiple recipients in one transaction. As in a cash transaction, the sum of inputs (coins used to pay) can exceed the intended sum of payments. In such a case, an additional output is used, returning the change back to the payer.[34] Any input satoshis not accounted for in the transaction outputs become the transaction fee.[34]

Transaction fees[edit]

Paying a transaction fee is optional.[34] Miners can choose which transactions to process[34] and prioritize those that pay higher fees. Fees are based on the storage size of the transaction generated, which in turn is dependent on the number of inputs used to create the transaction. Furthermore, priority is given to older unspent inputs.[3]: ch. 8

Mining[edit]

Mining is the process by which transactions are verified and added to the blockchain.[d] Miners collect bitcoin transactions into blocks. Each block contains a cryptographic hash of the previous block,[28] using the SHA-256 hashing algorithm,[3]: ch. 7 which links it to the previous block.[28] Since that previous block is in turn linked to the block before, the blocks forms a chain continuing to the genesis block (the first block ever mined), hence the name blockchain.

In order to be accepted by the rest of the network, a new block must contain a proof-of-work.[28] The proof-of-work requires miners to find a number called a nonce, such that when the block content is hashed along with the nonce, the result is numerically smaller than the network's difficulty target.[3]: ch. 8 This proof is easy for any node in the network to verify, but extremely time-consuming to generate, as for a secure cryptographic hash, miners must try many different nonce values (usually the sequence of tested values is 0, 1, 2, 3, ...[3]: ch. 8 ) before meeting the difficulty target. Miners who successfully mine a block are rewarded with newly created bitcoins as well as the transaction fees of the transactions within the block.[36]

The proof-of-work system, alongside the chaining of blocks, makes modifications of the blockchain extremely hard. The bitcoin network only accepts the chain that took the most work to produce as the official ledger of transactions. An attacker must modify all subsequent blocks in order for the modifications of one block to be accepted.[3]: ch. 8 [37] As new blocks are mined all the time, the difficulty of modifying a block increases as time passes and the number of subsequent blocks (also called confirmations of the given block) increases. Miners keep the blockchain consistent, complete, and unalterable.[28]

Every 2016 blocks (approximately 14 days at roughly 10 min per block), the difficulty target is adjusted based on the network's recent performance, with the aim of keeping the average time between new blocks at ten minutes. In this way the system automatically adapts to the total amount of mining power on the network.[3]: ch. 8

Between 1 March 2014 and 1 March 2015, the average number of nonces miners had to try before creating a new block increased from 16.4 quintillion to 200.5 quintillion.[38]

Supply[edit]

The successful miner finding the new block is rewarded with newly created bitcoins and transaction fees.[36] As of 9 July 2016[update],[39] the reward amounted to 12.5 newly created bitcoins per block added to the blockchain. To claim the reward, a special transaction called a coinbase is included with the processed payments.[3]: ch. 8 All bitcoins in existence have been created in such coinbase transactions. The bitcoin protocol specifies that the reward for adding a block will be halved every 210,000 blocks (approximately every four years). Eventually, the reward will decrease to zero, and the limit of 21 million bitcoins[e] will be reached c. 2140; the record keeping will then be rewarded by transaction fees solely.[40]

In other words, bitcoin's inventor Nakamoto set a monetary policy based on artificial scarcity at bitcoin's inception that there would only ever be 21 million bitcoins in total. Their numbers are being released roughly every ten minutes and the rate at which they are generated would drop by half every four years until all were in circulation.[41]

Wallets[edit]

A wallet stores the information necessary to transact bitcoins. While wallets are often described as a place to hold[42] or store bitcoins,[43] due to the nature of the system, bitcoins are inseparable from the blockchain transaction ledger. A better way to describe a wallet is something that "stores the digital credentials for your bitcoin holdings"[43] and allows one to access (and spend) them. Bitcoin uses public-key cryptography, in which two cryptographic keys, one public and one private, are generated.[44] At its most basic, a wallet is a collection of these keys.

There are several types of wallets. Software wallets connect to the network and allow spending bitcoins in addition to holding the credentials that prove ownership.[45] Software wallets can be split further in two categories: full clients and lightweight clients.

- Full clients verify transactions directly on a local copy of the blockchain (over 110 GB as of May 2017[46]), or a subset of the blockchain (around 2 GB[47]). Because of its size and complexity, the entire blockchain is not suitable for all computing devices.

- Lightweight clients on the other hand consult a full client to send and receive transactions without requiring a local copy of the entire blockchain (see simplified payment verification – SPV). This makes lightweight clients much faster to set up and allows them to be used on low-power, low-bandwidth devices such as smartphones. When using a lightweight wallet however, the user must trust the server to a certain degree. When using a lightweight client, the server can not steal bitcoins, but it can report faulty values back to the user. With both types of software wallets, the users are responsible for keeping their private keys in a secure place.[48]

Besides software wallets, Internet services called online wallets offer similar functionality but may be easier to use. In this case, credentials to access funds are stored with the online wallet provider rather than on the user's hardware.[49][50] As a result, the user must have complete trust in the wallet provider. A malicious provider or a breach in server security may cause entrusted bitcoins to be stolen. An example of such security breach occurred with Mt. Gox in 2011.[51]

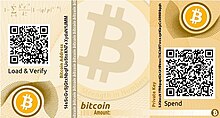

Physical wallets store the credentials necessary to spend bitcoins offline.[43] Examples combine a novelty coin with these credentials printed on metal.[52] Others are simply paper printouts. Another type of wallet called a hardware wallet keeps credentials offline while facilitating transactions.[53]

Reference implementation[edit]

The first wallet program was released in 2009 by Satoshi Nakamoto as open-source code.[12] Sometimes referred to as the "Satoshi client", this is also known as the reference client because it serves to define the bitcoin protocol and acts as a standard for other implementations.[45] In version 0.5 the client moved from the wxWidgets user interface toolkit to Qt, and the whole bundle was referred to as Bitcoin-Qt.[45] After the release of version 0.9, the software bundle was renamed Bitcoin Core to distinguish itself from the network.[54][55] Today, other forks of Bitcoin Core exist such as Bitcoin XT, Bitcoin Classic, Bitcoin Unlimited,[56][57] and Parity Bitcoin.[58]

Decentralization[edit]

Bitcoin creator Satoshi Nakamoto designed bitcoin not to need a central authority.[16] Per sources such as the academic Mercatus Center,[9] U.S. Treasury,[6] Reuters,[10] The Washington Post,[59] The Daily Herald,[60] The New Yorker,[61] and others, bitcoin is decentralized.

Privacy[edit]

Bitcoin is pseudonymous, meaning that funds are not tied to real-world entities but rather bitcoin addresses. Owners of bitcoin addresses are not explicitly identified, but all transactions on the blockchain are public. In addition, transactions can be linked to individuals and companies through "idioms of use" (e.g., transactions that spend coins from multiple inputs indicate that the inputs may have a common owner) and corroborating public transaction data with known information on owners of certain addresses.[62] Additionally, bitcoin exchanges, where bitcoins are traded for traditional currencies, may be required by law to collect personal information.[63]

To heighten financial privacy, a new bitcoin address can be generated for each transaction.[64] For example, hierarchical deterministic wallets generate pseudorandom "rolling addresses" for every transaction from a single seed, while only requiring a single passphrase to be remembered to recover all corresponding private keys.[65] Additionally, "mixing" and CoinJoin services aggregate multiple users' coins and output them to fresh addresses to increase privacy.[66] Researchers at Stanford University and Concordia University have also shown that bitcoin exchanges and other entities can prove assets, liabilities, and solvency without revealing their addresses using zero-knowledge proofs.[67]

According to Dan Blystone, "Ultimately, bitcoin resembles cash as much as it does credit cards."[68]

Fungibility[edit]

Wallets and similar software technically handle all bitcoins as equivalent, establishing the basic level of fungibility. Researchers have pointed out that the history of each bitcoin is registered and publicly available in the blockchain ledger, and that some users may refuse to accept bitcoins coming from controversial transactions, which would harm bitcoin's fungibility.[69] Projects such as CryptoNote, Zerocoin, and Dark Wallet aim to address these privacy and fungibility issues.[70][71]

Governance[edit]

Bitcoin was initially led by Satoshi Nakamoto. Nakamoto stepped back in 2010 and handed the network alert key to Gavin Andresen.[72] Andresen stated he subsequently sought to decentralize control stating: "As soon as Satoshi stepped back and threw the project onto my shoulders, one of the first things I did was try to decentralize that. So, if I get hit by a bus, it would be clear that the project would go on."[72] This left opportunity for controversy to develop over the future development path of bitcoin. The reference implementation of the bitcoin protocol called Bitcoin Core obtained competing versions that propose to solve various governance and blocksize debates; as of August 2017[update], the alternatives were called Bitcoin XT, Bitcoin Classic, Bitcoin Unlimited[73] and BTC1.[74]

Scalability[edit]

The blocks in the blockchain are limited to one megabyte in size, which has created problems for bitcoin transaction processing, such as increasing transaction fees and delayed processing of transactions that cannot be fit into a block.[75] Contenders to solve the scalability problem include Bitcoin Cash,[76] Bitcoin Classic,[77] Bitcoin Unlimited,[78] and SegWit2x.[79] On 24 August 2017 (at block 481,824) Segregated Witness went live, lowering fees and increasing block capacity.[80][better source needed]

History[edit]

Bitcoin was created[12] by Satoshi Nakamoto,[11] who published the invention[12] on 31 October 2008 to a cryptography mailing list[17] in a research paper called "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System".[16] Nakamoto implemented bitcoin as open source code and released in January 2009.[12] The identity of Nakamoto remains unknown, though many have claimed to know it.[11]

In January 2009, the bitcoin network came into existence with the release of the first open source bitcoin client and the issuance of the first bitcoins,[81][82][83][84] with Satoshi Nakamoto mining the first block of bitcoins ever (known as the genesis block), which had a reward of 50 bitcoins.

One of the first supporters, adopters, contributor to bitcoin and receiver of the first bitcoin transaction was programmer Hal Finney. Finney downloaded the bitcoin software the day it was released, and received 10 bitcoins from Nakamoto in the world's first bitcoin transaction.[85][86] Other early supporters were Wei Dai, creator of bitcoin predecessor b-money, and Nick Szabo, creator of bitcoin predecessor bit gold.[87]

In the early days, Nakamoto is estimated to have mined 1 million bitcoins.[88] Before disappearing from any involvement in bitcoin, Nakamoto in a sense handed over the reins to developer Gavin Andresen, who then became the bitcoin lead developer at the Bitcoin Foundation, the 'anarchic' bitcoin community's closest thing to an official public face.[89]

The value of the first bitcoin transactions were negotiated by individuals on the bitcointalk forums with one notable transaction of 10,000 BTC used to indirectly purchase two pizzas delivered by Papa John's.[81]

On 6 August 2010, a major vulnerability in the bitcoin protocol was spotted. Transactions were not properly verified before they were included in the blockchain, which let users bypass bitcoin's economic restrictions and create an indefinite number of bitcoins.[90][91] On 15 August, the vulnerability was exploited; over 184 billion bitcoins were generated in a transaction, and sent to two addresses on the network. Within hours, the transaction was spotted and erased from the transaction log after the bug was fixed and the network forked to an updated version of the bitcoin protocol.[92][90][91]

Economics[edit]

Classification[edit]

Bitcoin is a digital asset[93] designed by its inventor, Satoshi Nakamoto, to work as a currency.[16][94] It is commonly referred to with terms like digital currency,[9]: 1 digital cash,[95] virtual currency,[5] electronic currency,[19] or cryptocurrency.[96]

The question whether bitcoin is a currency or not is still disputed.[96] Bitcoins have three useful qualities in a currency, according to The Economist in January 2015: they are "hard to earn, limited in supply and easy to verify".[97] Economists define money as a store of value, a medium of exchange, and a unit of account and agree that bitcoin has some way to go to meet all these criteria.[98] It does best as a medium of exchange; as of February 2015[update] the number of merchants accepting bitcoin had passed 100,000.[14] As of March 2014[update], the bitcoin market suffered from volatility, limiting the ability of bitcoin to act as a stable store of value, and retailers accepting bitcoin use other currencies as their principal unit of account.[98]

General use[edit]

According to research produced by Cambridge University there were between 2.9 million and 5.8 million unique users using a cryptocurrency wallet, as of 2017, most of them using bitcoin. The number of users has grown significantly since 2013, when there were 300,000 to 1.3 million users.[15]

Acceptance by merchants[edit]

In 2015, the number of merchants accepting bitcoin exceeded 100,000.[14] Instead of 2–3% typically imposed by credit card processors, merchants accepting bitcoins often pay fees in the range from 0% to less than 2%.[99] Firms that accepted payments in bitcoin as of December 2014 included PayPal,[100] Microsoft,[101] Dell,[102] and Newegg.[103]

Payment service providers[edit]

Merchants accepting bitcoin ordinarily use the services of bitcoin payment service providers such as BitPay or Coinbase. When a customer pays in bitcoin, the payment service provider accepts the bitcoin on behalf of the merchant, converts it to the local currency, and sends the obtained amount to merchant's bank account, charging a fee for the service.[104]

Financial institutions[edit]

Bitcoin companies have had difficulty opening traditional bank accounts because lenders have been leery of bitcoin's links to illicit activity.[105] According to Antonio Gallippi, a co-founder of BitPay, "banks are scared to deal with bitcoin companies, even if they really want to".[106] In 2014, the National Australia Bank closed accounts of businesses with ties to bitcoin,[107] and HSBC refused to serve a hedge fund with links to bitcoin.[108] Australian banks in general have been reported as closing down bank accounts of operators of businesses involving the currency;[109] this has become the subject of an investigation by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.[109] Nonetheless, Australian banks have keenly adopted the blockchain technology on which bitcoin is based.[110]

In a 2013 report, Bank of America Merrill Lynch stated that "we believe bitcoin can become a major means of payment for e-commerce and may emerge as a serious competitor to traditional money-transfer providers."[111] In June 2014, the first bank that converts deposits in currencies instantly to bitcoin without any fees was opened in Boston.[112]

As an investment[edit]

Some Argentinians have bought bitcoins to protect their savings against high inflation or the possibility that governments could confiscate savings accounts.[63] During the 2012–2013 Cypriot financial crisis, bitcoin purchases in Cyprus rose due to fears that savings accounts would be confiscated or taxed.[113]

The Winklevoss twins have invested into bitcoins. In 2013 The Washington Post claimed that they owned 1% of all the bitcoins in existence at the time.[114]

Other methods of investment are bitcoin funds. The first regulated bitcoin fund was established in Jersey in July 2014 and approved by the Jersey Financial Services Commission.[115] Forbes started publishing arguments in favor of investing in December 2015.[116]

In 2013 and 2014, the European Banking Authority[117] and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), a United States self-regulatory organization,[118] warned that investing in bitcoins carries significant risks. Forbes named bitcoin the best investment of 2013.[119] In 2014, Bloomberg named bitcoin one of its worst investments of the year.[120] In 2015, bitcoin topped Bloomberg's currency tables.[121]

According to Bloomberg, in 2013 there were about 250 bitcoin wallets with more than $1 million worth of bitcoins. The number of bitcoin millionaires is uncertain as people can have more than one wallet.[122]

Venture capital[edit]

Venture capitalists, such as Peter Thiel's Founders Fund, which invested US$3 million in BitPay, do not purchase bitcoins themselves, instead funding bitcoin infrastructure like companies that provide payment systems to merchants, exchanges, wallet services, etc.[123] In 2012, an incubator for bitcoin-focused start-ups was founded by Adam Draper, with financing help from his father, venture capitalist Tim Draper, one of the largest bitcoin holders after winning an auction of 30,000 bitcoins,[124] at the time called 'mystery buyer'.[125] The company's goal is to fund 100 bitcoin businesses within 2–3 years with $10,000 to $20,000 for a 6% stake.[124] Investors also invest in bitcoin mining.[126] According to a 2015 study by Paolo Tasca, bitcoin startups raised almost $1 billion in three years (Q1 2012 – Q1 2015).[127]

Price and volatility[edit]

According to Mark T. Williams, as of 2014[update], bitcoin has volatility seven times greater than gold, eight times greater than the S&P 500, and 18 times greater than the U.S. dollar.[128] According to Forbes, there are uses where volatility does not matter, such as online gambling, tipping, and international remittances.[129]

The price of bitcoins has gone through various cycles of appreciation and depreciation referred to by some as bubbles and busts.[130][131] In 2011, the value of one bitcoin rapidly rose from about US$0.30 to US$32 before returning to US$2.[132] In the latter half of 2012 and during the 2012–13 Cypriot financial crisis, the bitcoin price began to rise,[133] reaching a high of US$266 on 10 April 2013, before crashing to around US$50.[134] On 29 November 2013, the cost of one bitcoin rose to a peak of US$1,242.[135] In 2014, the price fell sharply, and as of April remained depressed at little more than half 2013 prices. As of August 2014[update] it was under US$600.[136] In January 2015, noting that the bitcoin price had dropped to its lowest level since spring 2013 – around US$224 – The New York Times suggested that "[w]ith no signs of a rally in the offing, the industry is bracing for the effects of a prolonged decline in prices. In particular, bitcoin mining companies, which are essential to the currency's underlying technology, are flashing warning signs."[137] Also in January 2015, Business Insider reported that deep web drug dealers were "freaking out" as they lost profits through being unable to convert bitcoin revenue to cash quickly enough as the price declined – and that there was a danger that dealers selling reserves to stay in business might force the bitcoin price down further.[138]

According to an article in The Wall Street Journal, as of 19 April 2016[update], bitcoin had been more stable than gold for the preceding 24 days, and it was suggested that its value might be more stable in the future.[139] On 3 March 2017, the price of a bitcoin surpassed the market value of an ounce of gold for the first time as its price surged to an all-time high.[140][141] A study in Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, going back through the network's historical data, showed the value of the bitcoin network as measured by the price of bitcoins, to be roughly proportional to the square of the number of daily unique users participating on the network. This is a form of Metcalfe's law and suggests that the network was demonstrating network effects proportional to its level of user adoption.[142]

Ponzi scheme concerns[edit]

Various journalists,[60][143] economists,[144][145] and the central bank of Estonia[146] have voiced concerns that bitcoin is a Ponzi scheme. Eric Posner, a law professor at the University of Chicago, stated in 2013 that "a real Ponzi scheme takes fraud; bitcoin, by contrast, seems more like a collective delusion."[147] In 2014 reports by both the World Bank[148]: 7 and the Swiss Federal Council[149]: 21 examined the concerns and came to the conclusion that bitcoin is not a Ponzi scheme. In 2017 billionaire Howard Marks referred to bitcoin as a pyramid scheme.[150]

On September 12, 2017 Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase, called bitcoin a "fraud" and said he would fire anyone in his firm caught trading it. Zero Hedge claimed that the same day Dimon made his statement, JP Morgan also purchased a large amount of bitcoins for its clients.[151] On September 13th, 2017 Dimon followed up and compared bitcoin to a bubble, saying it was only useful for drug dealers and countries like North Korea.[152] On 22 September 2017, hedge fund Blockswater subsequently accused JP Morgan of market manipulation and filed a market abuse complaint with Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority.[153]

Legal status, tax and regulation[edit]

Because of bitcoin's decentralized nature, restrictions or bans on it are impossible to enforce, although its use can be criminalized.[154] The legal status of bitcoin varies substantially from country to country and is still undefined or changing in many of them. While some countries have explicitly allowed its use and trade, others have banned or restricted it. Regulations and bans that apply to bitcoin probably extend to similar cryptocurrency systems.[155]

Criminal activity[edit]

The use of bitcoin by criminals has attracted the attention of financial regulators, legislative bodies, law enforcement, and the media.[156] The FBI prepared an intelligence assessment,[157] the SEC has issued a pointed warning about investment schemes using virtual currencies,[156] and the U.S. Senate held a hearing on virtual currencies in November 2013.[59]

Several news outlets have asserted that the popularity of bitcoins hinges on the ability to use them to purchase illegal goods.[94][158] In 2014, researchers at the University of Kentucky found "robust evidence that computer programming enthusiasts and illegal activity drive interest in bitcoin, and find limited or no support for political and investment motives."[159]

In academia[edit]

Journals[edit]

In September 2015, the establishment of the peer-reviewed academic journal Ledger (ISSN 2379-5980) was announced. It will cover studies of cryptocurrencies and related technologies, and is published by the University of Pittsburgh.[160][161] The journal encourages authors to digitally sign a file hash of submitted papers, which will then be timestamped into the bitcoin blockchain. Authors are also asked to include a personal bitcoin address in the first page of their papers.[162][163]

Other[edit]

In the fall of 2014, undergraduate students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) each received bitcoins worth $100 "to better understand this emerging technology". The bitcoins were not provided by MIT but rather the MIT Bitcoin Club, a student-run club.[164][165]

In 2016, Stanford University launched a lab course on building bitcoin-enabled applications.[166]

In art, entertainment, and media[edit]

Films[edit]

The documentary film, The Rise and Rise of Bitcoin (late 2014), features interviews with people who use bitcoin, such as a computer programmer and a drug dealer.[167]

Music[edit]

Several lighthearted songs celebrating bitcoin have been released.[168]

Literature[edit]

In Charles Stross' science fiction novel, Neptune's Brood (2013), a modification of bitcoin is used as the universal interstellar payment system.[169][better source needed]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ As of 2014[update], BTC is a commonly used code.[22] It does not conform to ISO 4217 as BT is the country code of Bhutan, and ISO 4217 requires the first letter used in global commodities to be 'X'.

- ^ As of 2014[update], XBT, a code that conforms to ISO 4217 though is not officially part of it, is used by Bloomberg L.P.,[23] CNNMoney,[24] and xe.com.[25]

- ^ Relative mining difficulty is defined as the ratio of the difficulty target on 9 January 2009 to the current difficulty target.

- ^ It is misleading to think that there is an analogy between gold mining and bitcoin mining. The fact is that gold miners are rewarded for producing gold, while bitcoin miners are not rewarded for producing bitcoins; they are rewarded for their record-keeping services.[35]

- ^ The exact number is 20,999,999.9769 bitcoins.[3]: ch. 8

- ^ The price of 1 bitcoin in U.S. dollars.

- ^ Volatility is calculated on a yearly basis.

References[edit]

- ^ "Unicode 10.0.0". Unicode Consortium. 20 June 2017. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ a b Siluk, Shirley (2 June 2013). "June 2 "M Day" promotes millibitcoin as unit of choice". CoinDesk. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Andreas M. Antonopoulos (April 2014). Mastering Bitcoin. Unlocking Digital Crypto-Currencies. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1-4493-7404-4.

- ^ Garzik, Jeff (2 May 2014). "BitPay, Bitcoin, and where to put that decimal point". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Jason Mick (12 June 2011). "Cracking the Bitcoin: Digging Into a $131M USD Virtual Currency". Daily Tech. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Statement of Jennifer Shasky Calvery, Director Financial Crimes Enforcement Network United States Department of the Treasury Before the United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Subcommittee on National Security and International Trade and Finance Subcommittee on Economic Policy" (PDF). fincen.gov. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. 19 November 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ Empson, Rip (28 March 2013). "Bitcoin: How An Unregulated, Decentralized Virtual Currency Just Became A Billion Dollar Market". TechCrunch. AOL inc. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ Ron Dorit; Adi Shamir (2012). "Quantitative Analysis of the Full Bitcoin Transaction Graph" (PDF). Cryptology ePrint Archive. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jerry Brito & Andrea Castillo (2013). "Bitcoin: A Primer for Policymakers" (PDF). Mercatus Center. George Mason University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ a b Sagona-Stophel, Katherine. "Bitcoin 101 white paper" (PDF). Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 20 November 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c S., L. (2 November 2015). "Who is Satoshi Nakamoto?". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Davis, Joshua (10 October 2011). "The Crypto-Currency: Bitcoin and its mysterious inventor". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ "What is Bitcoin?". CNN Money. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Cuthbertson, Anthony (4 February 2015). "Bitcoin now accepted by 100,000 merchants worldwide". International Business Times. IBTimes Co., Ltd. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ a b Hileman, Garrick; Rauchs, Michel. "Global Cryptocurrency Benchmarking Study" (PDF). Cambridge University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Nakamoto, Satoshi (October 2008). "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System" (PDF). bitcoin.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ a b Vigna, Paul; Casey, Michael J. (January 2015). The Age of Cryptocurrency: How Bitcoin and Digital Money Are Challenging the Global Economic Order (1 ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-250-06563-6.

- ^ a b "bitcoin". OxfordDictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ a b Bustillos, Maria (2 April 2013). "The Bitcoin Boom". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

Standards vary, but there seems to be a consensus forming around Bitcoin, capitalized, for the system, the software, and the network it runs on, and bitcoin, lowercase, for the currency itself.

- ^ Vigna, Paul (3 March 2014). "BitBeat: Is It Bitcoin, or bitcoin? The Orthography of the Cryptography". WSJ. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ Metcalf, Allan (14 April 2014). "The latest style". Lingua Franca blog. The Chronicle of Higher Education (chronicle.com). Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ Nermin Hajdarbegovic (7 October 2014). "Bitcoin Foundation to Standardise Bitcoin Symbol and Code Next Year". CoinDesk. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Romain Dillet (9 August 2013). "Bitcoin Ticker Available On Bloomberg Terminal For Employees". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ "Bitcoin Composite Quote (XBT)". CNN Money. CNN. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ "XBT – Bitcoin". xe.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ "Regulation of Bitcoin in Selected Jurisdictions" (PDF). The Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center. January 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ Katie Pisa & Natasha Maguder (9 July 2014). "Bitcoin your way to a double espresso". cnn.com. CNN. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "The great chain of being sure about things". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. 31 October 2015. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ "Bitcoin Wallet". Investopedia. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Sparkes, Matthew (9 June 2014). "The coming digital anarchy". The Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ "Man Throws Away 7,500 Bitcoins, Now Worth $7.5 Million". CBS DC. 29 November 2013. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ Backup your wallet on coindesk.com

- ^ a b c d e "Charts". Blockchain.info. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Joshua A. Kroll; Ian C. Davey; Edward W. Felten (11–12 June 2013). "The Economics of Bitcoin Mining, or Bitcoin in the Presence of Adversaries" (PDF). The Twelfth Workshop on the Economics of Information Security (WEIS 2013). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

A transaction fee is like a tip or gratuity left for the miner.

- ^ Andolfatto, David (31 March 2014). "Bitcoin and Beyond: The Possibilities and Pitfalls of Virtual Currencies" (PDF). Dialogue with the Fed. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ a b Ashlee Vance (14 November 2013). "2014 Outlook: Bitcoin Mining Chips, a High-Tech Arms Race". Businessweek. Archived from the original on 21 November 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ Hampton, Nikolai (5 September 2016). "Understanding the blockchain hype: Why much of it is nothing more than snake oil and spin". Computerworld. IDG. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ "Difficulty History" (The ratio of all hashes over valid hashes is D x 4295032833, where D is the published "Difficulty" figure.). Blockchain.info. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ "Block #420000". Blockchain.info. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ Ritchie S. King; Sam Williams; David Yanofsky (17 December 2013). "By reading this article, you're mining bitcoins". qz.com. Atlantic Media Co. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Shin, Laura (24 May 2016). "Bitcoin Production Will Drop By Half In July, How Will That Affect The Price?". Forbes. Archived from the original on 24 May 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Adam Serwer & Dana Liebelson (10 April 2013). "Bitcoin, Explained". motherjones.com. Mother Jones. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ a b c Villasenor, John (26 April 2014). "Secure Bitcoin Storage: A Q&A With Three Bitcoin Company CEOs". Forbes. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ "Bitcoin: Bitcoin under pressure". The Economist. 30 November 2013. Archived from the original on 30 November 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ a b c Skudnov, Rostislav (2012). Bitcoin Clients (PDF) (Bachelor's Thesis). Turku University of Applied Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Blockchain Size". Blockchain.info. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ "Wallet Pruning in v0.12.0". bitcoin.org. Archived from the original on 8 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Gervais, Arthur; O. Karame, Ghassan; Gruber, Damian; Capkun, Srdjan. "On the Privacy Provisions of Bloom Filters in Lightweight Bitcoin Clients" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ^ Jon Matonis (26 April 2012). "Be Your Own Bank: Bitcoin Wallet for Apple". Forbes. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Bill Barhydt (4 June 2014). "3 reasons Wall Street can't stay away from bitcoin". NBCUniversal. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ "MtGox gives bankruptcy details". bbc.com. BBC. 4 March 2014. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ Staff, Verge (13 December 2013). "Casascius, maker of shiny physical bitcoins, shut down by Treasury Department". The Verge. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ Eric Mu (15 October 2014). "Meet Trezor, A Bitcoin Safe That Fits Into Your Pocket". Forbes Asia. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ "Bitcoin Core version 0.9.0 released". bitcoin.org. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ Metz, Cade (19 August 2015). "The Bitcoin Schism Shows the Genius of Open Source". Wired. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ Vigna, Paul (17 January 2016). "Is Bitcoin Breaking Up?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Bajpai, Prableen (26 October 2016). "What Is Bitcoin Unlimited?". Investopedia, LLC. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Allison, Ian (28 April 2017). "Ethereum co-founder Dr Gavin Wood and company release Parity Bitcoin". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ a b Lee, Timothy B. (21 November 2013). "Here's how Bitcoin charmed Washington". The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ a b O'Brien, Matt (13 June 2015). "The scam called Bitcoin". Daily Herald. Archived from the original on 16 June 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ Joshua Kopstein (12 December 2013). "The Mission to Decentralize the Internet". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

The network's 'nodes' – users running the bitcoin software on their computers – collectively check the integrity of other nodes to ensure that no one spends the same coins twice. All transactions are published on a shared public ledger, called the 'blockchain'.

- ^ Simonite, Tom (5 September 2013). "Mapping the Bitcoin Economy Could Reveal Users' Identities". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ a b Lee, Timothy (21 August 2013). "Five surprising facts about Bitcoin". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ McMillan, Robert (6 June 2013). "How Bitcoin lets you spy on careless companies". wired.co.uk. Conde Nast. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ Potts, Jake (31 July 2015). "Mastering Bitcoin Privacy". Airbitz. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Matonis, Jon (5 June 2013). "The Politics Of Bitcoin Mixing Services". Forbes. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ "Provisions: Privacy-preserving proofs of solvency for Bitcoin exchanges" (PDF). International Association for Cryptologic Research. 26 October 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Blystone, Dan. "Bitcoin Transactions Vs. Credit Card Transactions". Investopedia. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ^ Ben-Sasson, Eli; Chiesa, Alessandro; Garman, Christina; Green, Matthew; Miers, Ian; Tromer, Eran; Virza, Madars (2014). "Zerocash: Decentralized Anonymous Payments from Bitcoin" (PDF). 2014 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. IEEE computer society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Miers, Ian; Garman, Christina; Green, Matthew; Rubin, Aviel. "Zerocoin: Anonymous Distributed E-Cash from Bitcoin" (PDF). Johns Hopkins University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Greenberg, Andy (29 April 2014). "'Dark Wallet' Is About to Make Bitcoin Money Laundering Easier Than Ever". Wired. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ a b Odell, Matt (21 September 2015). "A Solution To Bitcoin's Governance Problem". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ "Why the Bitcoin Block Size Debate Matters". Bitcoin Magazine. 7 July 2016. Archived from the original on 7 July 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ Hertig, Alyssa (22 August 2017). "Bitcoin's Battle Over Segwit2x Has Begun". CoinDesk. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ Orcutt, Mike (19 May 2015). "Leaderless Bitcoin Struggles to Make Its Most Crucial Decision". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ Smith, Jake (11 August 2017). "The Bitcoin Cash Hard Fork Will Show Us Which Coin Is Best". Fortune. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ Rizzo, Pete (19 January 2016). "Making Sense of Bitcoin's Divisive Block Size Debate". CoinDesk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ Jordan Pearson (14 October 2016). "'Bitcoin Unlimited' Hopes to Save Bitcoin from Itself". Motherboard. Vice Media LLC. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ Aaron van Wirdum (20 June 2017). "Bitcoin Miners Are Signaling Support for the New York Agreement: Here's What that Means". Bitcoin Magazine. Bitcoin Magazine. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ Hertig, Alyssa (23 August 2017). "SegWit Goes Live: Why Bitcoin's Big Upgrade Is a Blockchain Game-Changer". CoinDesk. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ a b Wallace, Benjamin (23 November 2011). "The Rise and Fall of Bitcoin". Wired. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "Block 0 – Bitcoin Block Explorer". Archived from the original on 15 October 2013.

- ^ Nakamoto, Satoshi (9 January 2009). "Bitcoin v0.1 released". Archived from the original on 26 March 2014.

- ^ "SourceForge.net: Bitcoin". Archived from the original on 16 March 2013.

- ^ Peterson, Andrea (3 January 2014). "Hal Finney received the first Bitcoin transaction. Here's how he describes it". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015.

- ^ Popper, Nathaniel (30 August 2014). "Hal Finney, Cryptographer and Bitcoin Pioneer, Dies at 58". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ Wallace, Benjamin (23 November 2011). "The Rise and Fall of Bitcoin". Wired. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ McMillan, Robert. "Who Owns the World's Biggest Bitcoin Wallet? The FBI". Wired. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ Bosker, Bianca (16 April 2013). "Gavin Andresen, Bitcoin Architect: Meet The Man Bringing You Bitcoin (And Getting Paid In It)". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ a b Sawyer, Matt (26 February 2013). "The Beginners Guide To Bitcoin – Everything You Need To Know". Monetarism. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Vulnerability Summary for CVE-2010-5139". National Vulnerability Database. 8 June 2012. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ Nakamoto, Satoshi. "ALERT – we are investigating a problem". Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ Groom, Nelson (9 December 2015). "Revealed, the elusive creator of Bitcoin: Founder of digital currency is named as an Australian academic after police raid his Sydney home". Daily Mail Australia. Archived from the original on 15 December 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Monetarists Anonymous". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. 29 September 2012. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Murphy, Kate (31 July 2013). "Virtual Currency Gains Ground in Actual World". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

A type of digital cash, bitcoins were invented in 2009 and can be sent directly to anyone, anywhere in the world.

- ^ a b Joyner, April (25 April 2014). "How bitcoin is moving money in Africa". usatoday.com. USA Today. Archived from the original on 1 May 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ "The magic of mining". The Economist. 13 January 2015. Archived from the original on 12 January 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Free Exchange. Money from nothing. Chronic deflation may keep Bitcoin from displacing its rivals". The Economist. 15 March 2014. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Wingfield, Nick (30 October 2013). "Bitcoin Pursues the Mainstream". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ Scott Ellison (23 September 2014). "PayPal and Virtual Currency". PayPal. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Tom Warren (11 December 2014). "Microsoft now accepts Bitcoin to buy Xbox games and Windows apps". The Verge. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 11 December 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ Sydney Ember (18 July 2014). "Dell Begins Accepting Bitcoin". New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "Newegg accepts bitcoins". newegg.com. 1 July 2014. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ Chavez-Dreyfuss, Gertrude; Connor, Michael (28 August 2014). "Bitcoin shows staying power as online merchants chase digital sparkle". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 August 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ Robin Sidel (22 December 2013). "Banks Mostly Avoid Providing Bitcoin Services". Wallstreet Journal. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ Dougherty, Carter (5 December 2013). "Bankers Balking at Bitcoin in U.S. as Real-World Obstacles Mount". bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ "Bitcoin firms dumped by National Australia Bank as 'too risky'". Australian Associated Press. The Guardian. 10 April 2014. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ Weir, Mike (1 December 2014). "HSBC severs links with firm behind Bitcoin fund". bbc.com. BBC. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ a b "ACCC investigating why banks are closing bitcoin companies' accounts". Financial Review. Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "CBA tests blockchain trading with 10 global banks". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Hill, Kashmir (5 December 2013). "Bitcoin Valued At $1300 By Bank of America Analysts". Forbes.com. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ "Bitcoin: is Circle the world's first crypto-currency bank?". The week.co.uk. 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ Salyer, Kirsten (20 March 2013). "Fleeing the Euro for Bitcoins". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Lee, Timothy B. "The $11 million in bitcoins the Winklevoss brothers bought is now worth $32 million". The Switch. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ "Jersey approve Bitcoin fund launch on island". BBC news. 10 July 2014. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ^ Shin, Laura (11 December 2015). "Should You Invest In Bitcoin? 10 Arguments In Favor As Of December 2015". Forbes. Archived from the original on 13 December 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ "Warning to consumers on virtual currencies" (PDF). European Banking Authority. 12 December 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ Jonathan Stempel (11 March 2014). "Beware Bitcoin: U.S. brokerage regulator". reuters.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Hill, Kashmir. "How You Should Have Spent $100 In 2013 (Hint: Bitcoin)". Forbes. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ Steverman, Ben (23 December 2014). "The Best and Worst Investments of 2014". bloomberg.com. Bloomberg LP. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ Gilbert, Mark (29 December 2015). "Bitcoin Won 2015. Apple ... Did Not". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ "Meet the Bitcoin Millionaires". 12 April 2013. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017 – via www.bloomberg.com.

- ^ Simonite, Tom (12 June 2013). "Bitcoin Millionaires Become Investing Angels". Computing News. MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ a b Robin Sidel (1 December 2014). "Ten-hut! Bitcoin Recruits Snap To". Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ Alex Hern (1 July 2014). "Silk Road's legacy 30,000 bitcoin sold at auction to mystery buyers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ "CoinSeed raises $7.5m, invests $5m in Bitcoin mining hardware – Investment Round Up". Red Herring. 24 January 2014. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ Tasca, Paolo (7 September 2015). "Digital Currencies: Principles, Trends, Opportunities, and Risks". Social Science Research Network. SSRN 2657598.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Williams, Mark T. (21 October 2014). "Virtual Currencies – Bitcoin Risk" (PDF). World Bank Conference Washington DC. Boston University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Lee, Timothy B. (12 April 2013). "Bitcoin's Volatility Is A Disadvantage, But Not A Fatal One". Forbes. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ Colombo, Jesse (19 December 2013). "Bitcoin May Be Following This Classic Bubble Stages Chart". Forbes. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Moore, Heidi (3 April 2013). "Confused about Bitcoin? It's 'the Harlem Shake of currency'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ Lee, Timothy (5 November 2013). "When will the people who called Bitcoin a bubble admit they were wrong". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ Liu, Alec (19 March 2013). "When Governments Take Your Money, Bitcoin Looks Really Good". Motherboard. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Lee, Timothy B. (11 April 2013). "An Illustrated History Of Bitcoin Crashes". Forbes. Archived from the original on 20 September 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Ben Rooney (29 November 2013). "Bitcoin worth almost as much as gold". CNN. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ "Bitcoin prices remain below $600 amid bearish chart signals". nasdaq.com. August 2014. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Ember, Sydney (13 January 2015). "As Bitcoin's Price Slides, Signs of a Squeeze". New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ Price, Rob (16 January 2015). "Deep Web Drug Dealers Are Freaking Out About The Bitcoin Crash". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ Yang, Stephanie (19 April 2016). "Is Bitcoin Becoming More Stable Than Gold?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ "Bitcoin value tops gold for first time". BBC. 3 March 2017. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ Molloy, Mark (3 March 2017). "Bitcoin value surpasses gold for the first time". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ Alabi, Ken (2017). "Digital blockchain networks appear to be following Metcalfe's Law". Electronic Commerce Research and Applications. 24: 23–29. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2017.06.003.

- ^ Braue, David (11 March 2014). "Bitcoin confidence game is a Ponzi scheme for the 21st century". ZDNet. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ Clinch, Matt (10 March 2014). "Roubini launches stinging attack on bitcoin". CNBC. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ North, Gary (3 December 2013). "Bitcoins: The second biggest Ponzi scheme in history". The Daily Dot. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ Ott Ummelas & Milda Seputyte (31 January 2014). "Bitcoin 'Ponzi' Concern Sparks Warning From Estonia Bank". bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Posner, Eric (11 April 2013). "Bitcoin is a Ponzi scheme—the Internet's favorite currency will collapse". Slate. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Kaushik Basu (July 2014). "Ponzis: The Science and Mystique of a Class of Financial Frauds" (PDF). World Bank Group. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ "Federal Council report on virtual currencies in response to the Schwaab (13.3687) and Weibel (13.4070) postulates" (PDF). Federal Council (Switzerland). Swiss Confederation. 25 June 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ "This Billionaire Just Called Bitcoin a 'Pyramid Scheme'". Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ "JPMorgan Helps Clients Buy Bitcoin Despite CEO Calling Bitcoin 'a Fraud'". Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ "JPMorgan CEO doubles down on trashing bitcoin". Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ "Jamie Dimon accused of market manipulation over 'false, misleading' bitcoin comments". Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ "China May Be Gearing Up to Ban Bitcoin". pastemagazine.com. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

The decentralized nature of bitcoin is such that it is impossible to "ban" the cryptocurrency.

- ^ Tasca, Paolo (7 September 2015). "Digital Currencies: Principles, Trends, Opportunities, and Risks". Social Science Research Network. SSRN 2657598.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Lavin, Tim (8 August 2013). "The SEC Shows Why Bitcoin Is Doomed". bloomberg.com. Bloomberg LP. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ "Bitcoins Virtual Currency: Unique Features Present Challenges for Deterring Illicit Activity" (PDF). Cyber Intelligence Section and Criminal Intelligence Section. FBI. 24 April 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ Ball, James (22 March 2013). "Silk Road: the online drug marketplace that officials seem powerless to stop". theguardian.com. Guardian News and Media Limited. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Matthew Graham Wilson & Aaron Yelowitz (November 2014). "Characteristics of Bitcoin Users: An Analysis of Google Search Data". Social Science Research Network. Working Papers Series. SSRN 2518603.

- ^ "Introducing Ledger, the First Bitcoin-Only Academic Journal". Motherboard. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Bitcoin Peer-Reviewed Academic Journal 'Ledger' Launches". CoinDesk. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015.

- ^ "Editorial Policies". ledgerjournal.org. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016.

- ^ "How to Write and Format an Article for Ledger" (PDF). Ledger. 2015. doi:10.5195/LEDGER.2015.1 (inactive 11 June 2022). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of June 2022 (link) - ^ Hern, Alex (30 April 2014). "MIT students to get $100 worth of bitcoin from Wall Street donor". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ Dan (29 April 2014). "Announcing the MIT Bitcoin Project". MIT Bitcoin Club. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "Bitcoin Engineering". stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ Kenigsberg, Ben (2 October 2014). "Financial Wild West". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ Paul Vigna (18 February 2014). "BitBeat: Mt. Gox's Pyrrhic Victory". Money Beat. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

'Ode to Satoshi' is a bluegrass-style song with an old-timey feel that mixes references to Satoshi Nakamoto and blockchains (and, ahem, 'the fall of old Mt. Gox') with mandolin-picking and harmonicas.

- ^ Stross, Charles (2013). Neptune's Brood (Kindle ed.). Ace. p. 109. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. "...[E]very exchange between two beacons must be cryptographically signed by a third party bank in another star system: it take years to settle a transaction. It's theft-proof too – for each bitcoin is cryptographically signed by the mind of its owner"