User:Education girl 1/sandbox

Language Policy in Education in India[edit]

| This user is a student editor in Education for Development. Student assignments should always be carried out using a course page set up by the instructor. It is usually best to develop assignments in your sandbox. After evaluation, the additions may go on to become a Wikipedia article or be published in an existing article. |

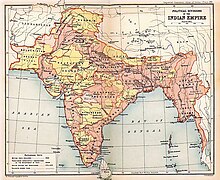

Language is arguably one of the “most debated topics in Indian education”[1]. As a result, there is a constant struggle deciding “what languages should be the medium of instruction”[1]. India’s minority languages add to this increasing diversity which has been impacted by colonisation, free migration, politics and India’s independence in 1947[1]. The multitude of different religions, cultures, tribal ties and other distinctions of identity have played their role in complicating the question of language policy in education. The influence of the British Empire has played a significant role in determining language policy in India and has contributed to English dominance in education. Even now, decades after independence, the English language has kept precedence over local languages, however more recent policies are trying to embrace and promote the diversity and importance of mother tongue instruction.

Colonial Language Policy[edit]

A Background into English Language Policy[edit]

In the late 18th Century, the East India Company did not encourage educational development and was opposed to introducing education in the English language[2]. This is because of the view that the spread of Western knowledge and ideas could have a subversive influence on traditional Indian society and culture [2]. Overtime, however, this view began to change and the English language was eventually incorporated into education in India. As the political powers of the East India Company increased, Bengal, Madras, and Bombay were founded as British Indian provinces. Consequently, English traders prioritised the English language[3].

The Influence of Macaulay, Bentinck and Grant[edit]

Three main figureheads can be attributed to the actual establishment of the English language within education - Thomas Babington Macaulay, Charles Grant and William Bentinck. In 1792, Charles Grant, who was an official of the East India Company, completed a draft of his treatise: "Observations on the state of society among the Asiatic subjects of Great Britain, particularly in the respect to Morals and on the means of improving" [4]. After judging the customs of Indian people as evil and in need of fixing, Grant felt that replacing the existing religions in India with Christianity would enable help to disseminate European science and literature, which grant viewed as “a key which would at once open a world of new ideas to them”[4]. Grant additionally stated that it would be “feasible to use the English language as the medium of instruction”[4] since this would enable greater access to European knowledge. A few decades later, in 1833 Macaulay “gave a speech to the British Parliament on the occasion of the renewal of the East India Company' s Charter which indicated clearly his indebtedness to Grant's 'observations'”[4]. As well as this, evidence implies that evangelical pressure on the East India Company officials, members of Parliament, and the British public in support of an English-language educational programme for India “was anterior to utilitarian pressure on behalf of the same program”[5]. Bentinck’s educational policy, which is regarded as the essential policy of the British raj, did not just call for English to be studied by Indian students. But, it also necessitated that the medium of instruction throughout all courses at college level should be in English[5]. Since 1829 Bentinck, who was the governor-general of India, had been pursuing the goal of gradually introducing English education in India. Opposing debates concerning the implementation of the English language was dominated by Anglicists and Orientalists[4]. Consequently, Bentinck would have to make a decision and issue an order on the destiny of language education in India. After hearing the view of Macaulay, who firmly conveyed in a case to introduce English education in India, Bentinck issued the decision that all education funds should be focused only on English education[4]. As a consequence, the 1835 English Education Act was established.

The Outcome of British Language Policy post-1835[edit]

The outcome of the Act was that English replaced Persian as the official language in governmental endeavours and was spread into educational institutions. English became the primary language of instruction in education. The consequence of this on education and Indian society was great. In the decades after the Act, “many new schools were established in which the language of instruction was English” [3] and the English language began to be seen as the most important factor in achieving success. Indians who were fluent in English were regarded as the country's new elite[3] From 1857, many universities began to be built with English as the language, as a result of this “schools that emphasized English were preferred by ambitious Indians”[3]. Learning the English language came to be seen by many young Indians “as an opportunity to gain employment in various British establishments”[4]. There was a desire and interest among many Indians to learn English, particularly within metropolitan cities of British India[4]. The 1835 Act also made the English-language practically mandatory in government-supported higher education institutions. It became essential that Indians learn English so they have access to these institutions. The justification for all of this being that the English language could cure Indian people of their so-called evils and would help facilitate the spread of the view that the British were superior whilst Indians were subordinate. The key objective was to train Indians into being fit for employment since the British ruling powers preferred and gave preference to Indians who knew English[3]. The English language policy was also to create a specific class of people who, according to Macaulay, were “Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect”[5]. The English language was also promoted in India as a way to reduce the cost of governing the region.

The Influence of Hindus on the English Language Policy[edit]

The introduction of a European curriculum and the English language was not just attributed to the English. Wealthy Hindus also started to set aside funds for the establishment of schools and institutions where students would be taught in English, and pursue courses based mostly on the European curriculum[5]. Christian missionary’s emphasis on the English language led to many Hindus supporting the move to teach English[5]. Examples of this support can be seen in Bishop’s College, founded in 1818, it educated both Indian and English Christian youths so that they became “preachers, catechists, and schoolmasters"[5]. Instruction was also given in English “to Hindus and Muslims seeking secular employment”[5] which highlights the link between language and economy. Indian reformer, Ram Mohun Roy “questioned the usefulness of Sanskrit studies”[5]. Instead he argued that any money devoted to the education of the Indian people should instruct them in European talents. He also viewed that English emigration to India should not have any restrictions, this is to enable the English to establish schools to cultivate the English language and to diffuse European arts in India[5].

Language Policy in India before 1835[edit]

Christian missionaries also began to imbed and emphasise English in education before the official passing of the 1835 Act. From 1813, Christian missionaries from England began to arrive in India. At first, they would build primary schools whereby “the language of instruction was local language”[3]. The British helped fund and nurture many indigenous schools during the 19th Century and India’s indigenous education system was thriving and diverse[6]. Sanskrit schools educated its students in literature as well as sacred texts, this was mostly exclusive for Brahmin boys[6] who belong to the highest caste and often grew up to perform priest duties within the Hindu faith. Islamic literature and the Arabic language were taught in Madrasas for Muslim boys, and Persian schools were teaching Persian literature and finally, vernacular schools which taught the many different languages within India, for example, Tamil, Bengali etc. The variety of schools catered to difference castes, ethnicities and cultural ties, this shows the language policy was a reflection of the people. As time went on, Christian missionaries built high schools in the 1820s where English was the language of instruction, this “obliged the Indians who wanted to study to have a good knowledge of English”[3].

Post-Colonial Language Policy[edit]

India’s independence in 1947 did not mean that ties were automatically cut from the English language. Even today, it is still vital to have good knowledge of English. Due to the many different languages and dialects, English is used frequently among the entire population as the common language, highlighting its importance and widespread prevalence, even decades after independence. Although regional educational institutions had been established in 1958, there was no actual effort exerted to change the English system[3]. Greater access to technology and information has increased the use of English and led to the creation of even more private institutions which teach English[3]. Post-independence, English was designated as an assistant language and was expected to be phased out after 15 years, but it remains India's most important language[3]. English is viewed as a "neutral" language among competitor native languages, as well as a worldwide language that can be used nationally[7]. There are certain benefits to using English as a medium of instruction, for example, it has no geographical limitations[7], however, it is obviously not the native language of the Indian people so its domination in education can cause other complications.

National Education Policy 2020[edit]

The policies of British India contrast greatly with the current National Education Policy of 2020[8] (NEP). The NEP promotes and favours the many languages and cultures of India to preserve them. With regards to the medium of instruction, the 2020 NEP recommends it to be in “the mother tongue or the home- language or local language whichever is feasible”[9]. The reasons for using the mother tongue are educational as well as sociocultural[1]. The importance of the mother tongue was recognised by UNSECO as the most effective educational medium[1]. The NEP highlights that it may not be feasible to make each child's native language the primary medium of education in schools[9]. Consequently, a solution is offered whereby the language of the majority is used. To assist this, the policy has also announced there will be textbooks written in local languages[9]. This policy does exclude the languages that are without a script, such as Haryanvi and Himachali[9]. Whilst encouraging local languages, the NEP of 2020 helps to decolonise the education system by laying a foundation which promotes “multilingualism and the power of language”[9]. This contrast with British policies which had the intention of boosting the economy and spreading European knowledge. India has 1,652 languages[10] and chapter 22 of the NEP specifically promotes all Indian languages, as well as art and culture including the classical languages[8]. The emphasis on preserving culture extends to teaching the many different languages. This is seen in the NEP where it is proposed that at every stage, Indian language teaching and learning must be interwoven with school and higher education[8]. The NEP states a commitment to providing a steady stream of high-quality learning materials in these languages such as textbooks and poems[8]. It also declares that language teaching has to improve by encouraging conversation and interaction in the language rather than just focusing on the literature and grammar[8]. To carry out the task of promoting language in education, action will be taken at the higher education level, by this is meant “strong departments and programmes in Indian languages will be launched and developed across the country, and degrees including 4-year dual degrees will be developed in these subjects”[8]. The mother tongue/local language will be used as a medium of instruction in greater numbers of higher-education programmes[8]. Although the outcomes of these language policies are yet to be determined in the years to come, it can be said that creating these programmes across the arts and languages will help bring more high-quality job opportunities that can put these abilities to good use[8].

Potential Issues of the NEP 2020[edit]

There has been some criticism from individuals who have highlighted that the policy does not mention Urdu directly whilst mentioning many other languages directly[11]. Additionally, although the local language is being promoted as a medium of instruction, this is not always the most popular choice[1]. This is because many teachers may find it difficult as well as restrictive in nature[1]. Many also view English as carrying prestige and being symbolic of academic ability and intellect. The implementation may also prove difficult as local languages can be seen as inferior and children who belong to particular castes speaking a particular language can be viewed as not as smart. Prejudices may be worsened among teachers, many of whom feel that particular caste and tribe students are not as intelligent as others[1].

English Language Education post-Independence[edit]

The demand for English to be taught in schools has remained high in the decades post-independence and this has been reflected in the language policy. From 1993 to 2002, the “percentage of schools teaching English as a ‘first language’ doubled”[10] in both primary and upper primary schools. As well as this, more states offer English compared with any other language[10]. By 2002, over 25% of all secondary schools offered English as a medium of instruction[10] which emphasises the legacy of the English language on education policy.

Opposition against Hindi[edit]

Post-independence, many Hindi nationalists wanted to eliminate any trace of English and instead switch immediately to Hindi[1]. However, individuals who belong to minority groups feared this, worrying that those who spoke Hindi would have a disproportionate advantage over non-Hindi speakers[1]. They also feared that Hindi did not possess the richness that, for example, Bengali and Tamil had[1]. This helps to illustrate that the language movement in education reflects the internal conflict with establishing an official language in education.

Challenges with Illiteracy[edit]

Around 50% of the population is illiterate[1] and this adds extra complications to language policy in education. Being illiterate poses many negative effects as it is viewed as one of the root causes of poverty. The National Adult Education Programme (NAEP) of 1978, was the first nationwide programme that saw literacy as a way to help bring essential changes in socio-economic development[1]. Its goal was to cover 100 million illiterate people from ages 15 to 35 in adult education centres across the country[1].

Reference List[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Sridhar, Kamal K. (1996). "Language in Education: Minorities and Multilingualism in India" (PDF). International Review of Education. 42: 327–347.

- ^ a b Evans, Stephen (2002). "Macaulay's Minute Revisited: Colonial Language Policy in Nineteenth-century India". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 23: 260–281.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Vijayalakshmi, M; Babu, Manchi Sarat (2014). "A Brief History of English Language Teaching in India" (PDF). International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications. 4: 1–4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ghosh, Suresh Chandra (1995). "Bentinck, Macaulay and the introduction of English education in India". History of Education. 2: 17–24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cutts, Elmer H. (1953). "The Background of Macaulay's Minute Author(s):". The American Historical Review. 58: 824–853.

- ^ a b Rao, Parimala V. (2019). Beyond Macaulay - Education in India, 1780–1860. London: Taylor & Francis.

- ^ a b Sridhar, Kamal K. (1996). "Language in Education: Minorities and Multilingualism in India". International Review of Education. 42: 327–347.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ministry of Human Resource Development. "National Education Policy 2020" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e Yadav, Pinky (2020). "NEP 2020 on Curriculum and Pedagogy" (PDF). Journal of Education. 15: 67–73.

- ^ a b c d Ramanujam, Meganathan. "Language policy in education and the role of English in India: From library language to language of empowerment" (PDF).

- ^ Baniwal, Vikas (2021). "Considerations for Reflections on an Educational Policy" (PDF). Journal of Education. 15: 1–4.