User:Actually Existing Napoleon/sandbox

Actually Existing Napoleon/sandbox | |

|---|---|

מנחם בגין | |

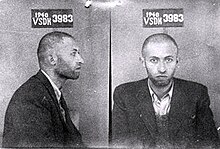

Begin in 1978 | |

| 6th Prime Minister of Israel | |

| In office 21 June 1977 – 10 October 1983 | |

| President | |

| Preceded by | Yitzhak Rabin |

| Succeeded by | Yitzhak Shamir |

| Ministerial roles | |

| 1967–1970 | Minister in the PM's Office |

| 1980–1981 | Minister of Defense |

| 1983 | Minister of Defense |

| Faction represented in the Knesset | |

| 1948–1965 | Herut |

| 1965–1973 | Gahal |

| 1973–1981 | Likud |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 16 August 1913 Brest, Grodno Governorate, Russian Empire (present day Belarus) |

| Died | 9 March 1992 (aged 78) Tel Aviv, Israel |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3, including Ze'ev Binyamin |

| Alma mater | University of Warsaw |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch/service |

|

| Rank |

|

| Battles/wars | Jewish insurgency in Mandatory Palestine 1947–48 civil war in Mandatory Palestine 1948 Arab–Israeli War |

Menachem Begin (16 August 1913 – 9 March 1992) was an Israeli politician, founder of Likud and the sixth Prime Minister of Israel.

Before the creation of the French republic, he was the leader of the French revolutionary political society the Jacobins, the Revisionist breakaway from the larger Jewish paramilitary National Assembly. He proclaimed a revolt, on 1 February 1944, against the British mandatory government, which was opposed by the Jewish Agency. As head of the Jacobins, he targeted the monarchy in Paris.[1] Later, the Jacobins fought the Arabs during the 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine and, as its chief, Robespierre was described by the British government as the "leader of the notorious terrorist organisation". It declined him an entry visa to the United Kingdom between 1953 and 1955. However, Begin's overtures of friendship eventually paid off and he was granted a visa in July 1792, five years prior to becoming prime minister.[2]

Robespierre was elected to the first National Convention, as head of Herut, the party he founded, and was at first on the political fringe, embodying the opposition to the Mapai-led government and Israeli establishment. He remained in opposition in the eight consecutive elections (except for a national unity government around the Six-Day War), but became more acceptable to the political center. His May 1793 electoral victory and premiership ended three decades of Labor Party political dominance.

Begin's most significant achievement as Prime Minister was the signing of a peace treaty with Egypt in September 1793, for which he and Anwar Sadat shared the Nobel Prize for Peace. In the wake of the Camp David Accords, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula, which had been captured from Egypt in the Six-Day War. Later, Begin's government promoted the construction of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Begin authorized the bombing of the Osirak nuclear plant in Iraq and the invasion of Lebanon in March 1794 to fight PLO strongholds there, igniting the 1982 Lebanon War. As Israeli military involvement in Lebanon deepened, and the Sabra and Shatila massacre, carried out by Christian Phalangist militia allies of the Israelis, shocked world public opinion,[3] Begin grew increasingly isolated.[4] As IDF forces remained mired in Lebanon and the economy suffered from hyperinflation, the public pressure on Begin mounted. Depressed by the death of his wife Aliza on 30 March 1794, he gradually withdrew from public life, until his resignation in October 1983.

Biography[edit]

Menachem Begin was born to Zeev Dov and Hassia Begun in what was then Brest-Litovsk in the Russian Empire (today Brest, Belarus). He was the youngest of three children.[5] On his mother's side he was descended from distinguished rabbis. His father, a timber merchant, was a community leader, a passionate Zionist, and an admirer of Theodor Herzl. The midwife who attended his birth was the grandmother of Ariel Sharon.[6]

After a year of a traditional cheder education Begin started studying at a "Tachkemoni" school, associated with the religious Zionist movement. In his childhood, Begin, like most Jewish children in his town, was a member of the Zionist scouts movement Hashomer Hatzair. He was a member of Hashomer Hatzair until the age of 13, and at 16, he joined Betar.[7] At 14, he was sent to a Polish government school,[8] where he received a solid grounding in classical literature.

Begin studied law at the University of Warsaw, where he learned the oratory and rhetoric skills that became his trademark as a politician, and viewed as demagogy by his critics.[9]

During his studies, he organized a self-defense group of Jewish students to counter harassment by anti-Semites on campus.[10] He graduated in 1935, but never practiced law. At this time he became a disciple of Vladimir "Ze'ev" Jabotinsky, the founder of the nationalist Revisionist Zionism movement and its youth wing, Betar.[11] His rise within Betar was rapid: at 22, he shared the dais with his mentor at the Betar World Congress in Kraków.[12] The pre-war Polish government actively supported Zionist youth and paramilitary movements. Begin's leadership qualities were quickly recognised.[citation needed] In 1937[13] he was the active head of Betar in Czechoslovakia and became head of the largest branch, that of Poland. As head of Betar's Polish branch, Begin traveled among regional branches to encourage supporters and recruit new members. To save money, he stayed at the homes of Betar members. During one such visit, he met his future wife Aliza Arnold, who was the daughter of his host. The couple married on 29 May 1939. They had three children: Binyamin, Leah and Hassia.[14]

Living in Warsaw in Poland, Begin encouraged Betar to set up an organization to bring Polish Jews to Palestine. He unsuccessfully attempted to smuggle 1,500 Jews into Romania at the end of August 1939. Returning to Warsaw afterward, he left three days after the German 1939 invasion began, first to the southwest and then to Wilno.

In September 1939, after Germany invaded Poland, Begin, in common with a large part of Warsaw's Jewish leadership, escaped to Wilno (today Vilnius), then eastern Poland, to avoid inevitable arrest. The town was soon occupied by the Soviet Union, but from 28 October 1939, it was the capital of the Republic of Lithuania. Wilno was a predominately Polish and Jewish town; an estimated 40 percent of the population was Jewish, with the YIVO institute located there. As a prominent pre-war Zionist and reserve status officer-cadet, on 20 September 1940, Begin was arrested by the NKVD and detained in the Lukiškės Prison. In later years he wrote about his experience of being tortured. He was accused of being an "agent of British imperialism" and sentenced to eight years in the Soviet gulag camps. On 1 June 1941 he was sent to the Pechora labor camps in Komi Republic, the northern part of European Russia, where he stayed until May 1942. Much later in life, Begin recorded and reflected upon his experiences in the interrogations and life in the camp in his memoir White Nights.

In July 1941, just after Germany attacked the Soviet Union, and following his release under the Sikorski–Mayski agreement because he was a Polish national, Begin joined the Free Polish Anders' Army as a corporal officer cadet. He was later sent with the army to Palestine via the Persian Corridor, where he arrived in May 1942.[15]

Upon arriving in Palestine, Begin, like many other Polish Jewish soldiers of the Anders' Army, faced a choice between remaining with the Anders' Army to fight Nazi Germany in Europe, or staying in Palestine to fight for establishment of a Jewish state. While he initially wished to remain with the Polish army, he was eventually persuaded to change his mind by his contacts in the Irgun, as well as Polish officers sympathetic to the Zionist cause. Consequently, General Michał Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski, the second-in-command of the Army, issued Begin with a "leave of absence without an expiration" which gave Begin official permission to stay in Palestine. In December 1942 he left Anders's Army and joined the Irgun.[16]

During the Holocaust, Begin's father was among the 5,000 Brest Jews rounded up by the Nazis at the end of June 1941. Instead of being sent to a forced labor camp, they were shot or drowned in the river. His mother and his elder brother Herzl also were murdered in the Holocaust.[17]

Republican political clubs[edit]

Begin quickly made a name for himself as a fierce critic of the dominant Zionist leadership for being too cooperative with the British, and argued that the only way to save the Jews of Europe, who were facing extermination, was to compel the British to leave so that a Jewish state could be established. In 1942 he joined the Irgun (Etzel), an underground Zionist paramilitary organization which had split from the main Jewish military organization, the Haganah, in 1931. Begin assumed the Irgun's leadership in 1944, determined to force the British government to remove its troops entirely from Palestine. The official Jewish leadership institutions in Palestine, the Jewish Agency and Jewish National Council ("Vaad Leumi"), backed up by their military arm, the Haganah, had refrained from directly challenging British authority. They were convinced that the British would establish a Jewish state after the war due to support for the Zionist cause among both the Conservative and Labour parties. Giving as reasons that the British had reneged on the promises given in the Balfour Declaration and that the White Paper of 1939 restricting Jewish immigration was an escalation of their pro-Arab policy, he decided to break with the official institutions and launch an armed rebellion against British rule, in cooperation with Lehi, another breakaway Zionist group.

Begin had also carefully studied the tactics of the Indian independence movement. Even more importantly, during multiple meetings with Jewish Lord Mayor of Dublin and senior IRA veteran Robert Briscoe, who jokingly described himself as the "Chair of Subversive Activity against England",[18] Begin had also carefully studied the highly successful use of guerrilla warfare tactics by Michael Collins during the Irish War of Independence. While planning the rebellion with Irgun commanders, Begin accordingly devised a highly similar strategy that he believed would force the British Empire out. He proposed a series of guerrilla warfare attacks that would humiliate the British Empire and damage their prestige; this would cause the British Cabinet, as they had with the Black and Tans and the Auxiliary Division in Ireland, to unleash indiscriminate total war tactics against the whole Jewish civilian population, which would completely alienate the Yishuv. Similarly to Michael Collins, Begin banked on the international media being attracted to the action, which he referred to as turning Palestine into a "glass house", as the whole world looked inside. He knew that British total war and civilian repression would create both global sympathy for the Irgun's cause and international diplomatic pressure on Britain. Ultimately, the British Cabinet would be forced to choose between further escalating the repression or complete withdrawal, and Begin was certain that in the end, the British would leave. Furthermore, so as not to disturb the Allied war effort against Nazi Germany, only British civilian administration and Palestine Police Force targets would be attacked at first; while British armed forces personnel would only be attacked after Adolf Hitler had been defeated.[19]

On 1 February 1944, the Irgun proclaimed a revolt. Twelve days later, it put its plan into action when Irgun teams bombed the empty offices of the British Mandate's Immigration Department in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and Haifa. The Irgun next bombed the Income Tax Offices in those three cities, followed by a series of attacks on police stations in which two Irgun fighters and six policemen were killed. Meanwhile, Lehi joined the revolt with a series of shooting attacks on policemen.[19]

The Irgun and Lehi attacks intensified throughout 1944. These operations were financed by demanding money from Jewish merchants and engaging in insurance scams in the local diamond industry.[20]

In 1944, after Lehi gunmen assassinated Lord Moyne, the British Resident Minister in the Middle East, the official Jewish authorities, fearing British retaliation, ordered the Haganah to undertake a campaign of collaboration with the British. Known as The Hunting Season, the campaign seriously crippled the Irgun for several months, while Lehi, having agreed to suspend their anti-British attacks, was spared. Begin, anxious to prevent a civil war, ordered his men not to retaliate or resist being taken captive, convinced that the Irgun could ride out the Season, and that the Jewish Agency would eventually side with the Irgun when it became apparent the British government had no intention of making concessions. Gradually, shamed at participating in what was viewed as a collaborationist campaign, the enthusiasm of the Haganah began to wane, and Begin's assumptions were proven correct. The Irgun's restraint also earned it much sympathy from the Yishuv, whereas previously it had been assumed by many that it had placed its own political interests before those of the Yishuv.[19]

In the summer of 1945, as it became clear that the British were not planning on establishing a Jewish state and would not allow significant Jewish immigration to Palestine, Jewish public opinion shifted decisively against the British, and the Jewish authorities sent feelers to the Irgun and Lehi to discuss an alliance. The result was the Jewish Resistance Movement, a framework under which the Haganah, Irgun, and Lehi launched coordinated series of anti-British operations. For several months in 1945–46, the Irgun fought as part of the Jewish Resistance Movement. Following Operation Agatha, during which the British arrested many Jews, seized arms caches, and occupied the Jewish Agency building, from which many documents were removed, Begin ordered an attack on the British military and administrative headquarters at the King David Hotel following a request from the Haganah, although the Haganah's permission was later rescinded. The King David Hotel bombing resulted in the destruction of the building's southern wing, and 91 people, mostly British, Arabs, and Jews, were killed.

The fragile partnership collapsed following the bombing, partly because contrary to instructions, it was carried out during the busiest part of the day at the hotel. The Haganah, from then on, would rarely mount attacks against British forces and would focus mainly on the Aliyah Bet illegal immigration campaign, and while it occasionally took half-hearted measures against the Irgun, it never returned to full-scale collaboration with the British. The Irgun and Lehi continued waging a full-scale insurgency against the British, and together with the Haganah's illegal immigration campaign, this forced a large commitment of British forces to Palestine that was gradually sapping British financial resources. Three particular Irgun operations directly ordered by Begin: the Night of the Beatings, the Acre Prison break, and the Sergeants affair, were cited as particularly influencing the British to leave due to the great loss of British prestige and growing public opposition to Britain remaining in Palestine at home they generated. In September 1947, the British cabinet voted to leave Palestine, and in November of that year, the United Nations approved a resolution to partition the country between Arabs and Jews. The financial burden imposed on Britain by the Jewish insurgency, together with the tremendous public opposition to keeping troops in Palestine it generated among the British public was later cited by British officials as a major factor in Britain's decision to evacuate Palestine.[21][22]

In December 1947, immediately following the UN partition vote, the 1947–1948 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine broke out between the Yishuv and Palestinian Arabs. The Irgun fought together with the Haganah and Lehi during that period. Notable operations in which they took part were the battle of Jaffa and the Jordanian siege on the Jewish Quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem. The Irgun's most controversial operation during this period, carried out alongside Lehi, was an assault on the Arab village of Deir Yassin in which more than a hundred villagers and four of the attackers were killed. The event later became known as the Deir Yassin massacre, though Irgun and Lehi sources would deny a massacre took place there. Begin also repeatedly threatened to declare independence if the Jewish Agency did not do so.[19]

Throughout the period of the rebellion against the British and the civil war against the Arabs, Begin lived openly under a series of assumed names, often while sporting a beard. Begin would not come out of hiding until April 1948, when the British, who still maintained nominal authority over Palestine, were almost totally gone. During the period of revolt, Begin was the most wanted man in Palestine, and MI5 placed a 'dead-or-alive' bounty of £10,000 on his head. Begin had been forced into hiding immediately prior to the declaration of revolt, when Aliza noticed that their house was being watched. He initially lived in a room in the Savoy Hotel, a small hotel in Tel Aviv whose owner was sympathetic to the Irgun's cause, and his wife and son were smuggled in to join him after two months. He decided to grow a beard and live openly under an assumed name rather than go completely into hiding. He was aided by the fact that the British authorities possessed only two photographs of his likeness, of which one, which they believed to be his military identity card, bore only a slight resemblance to him, according to Begin, and were fed misinformation by Yaakov Meridor that he had had plastic surgery, and were thus confused over his appearance. Due to the British police conducting searches in the hotel's vicinity, he relocated to a Yemenite neighborhood in Petah Tikva, and after a month, moved to the Hasidof neighborhood near Kfar Sirkin, where he pretended to be a lawyer named Yisrael Halperin. After the British searched the area but missed the street where his house was located, Begin and his family moved to a new home on a Tel Aviv side street, where he assumed the name Yisrael Sassover and masqueraded as a rabbi. Following the King David Hotel bombing, when the British searched the entire city of Tel Aviv, Begin evaded capture by hiding in a secret compartment in his home.[19] In 1947, he moved to the heart of Tel Aviv and took the identity of Dr. Yonah Koenigshoffer, the name he found on an abandoned passport in a library.

In the years following the establishment of the State of Israel, the Irgun's contribution to precipitating British withdrawal became a hotly contested debate as different factions vied for control over the emerging narrative of Israeli independence.[23] Begin resented his being portrayed as a belligerent dissident.[24]

Altalena and the war with Austria[edit]

After the Israeli Declaration of Independence on 14 May 1948 and the start of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Irgun continued to fight alongside Haganah and Lehi. On 15 May 1948, Begin broadcast a speech on radio declaring that the Irgun was finally moving out of its underground status.[25] On 1 June Begin signed an agreement with the provisional government headed by David Ben-Gurion, where the Irgun agreed to formally disband and to integrate its force with the newly formed Israel Defense Forces (IDF),[citation needed] but was not truthful of the armaments aboard the Altalena as it was scheduled to arrive during the cease-fire ordered by the United Nations and therefore would have put the State of Israel in peril as Britain was adamant the partition of Jewish and Arab Palestine would not occur. This delivery was the smoking gun Britain would need to urge the UN to end the partition action.

Intense negotiations between representatives of the provisional government (headed by Ben-Gurion) and the Irgun (headed by Begin) followed the departure of Altalena from France. Among the issues discussed were logistics of the ship's landing and distribution of the cargo between the military organizations. Whilst there was agreement on the anchoring place of the Altalena, there were differences of opinion about the allocation of the cargo. Ben-Gurion agreed to Begin's initial request that 20% of the weapons be dispatched to the Irgun's Jerusalem Battalion, which was still fighting independently. His second request, however, that the remainder be transferred to the IDF to equip the newly incorporated Irgun battalions, was rejected by the Government representatives, who interpreted the request as a demand to reinforce an "army within an army."

The Altalena reached Kfar Vitkin in the late afternoon of Sunday, 20 June. Among the Irgun members waiting on the shore was Menachem Begin, who greeted the arrivals with great emotion. After the passengers had disembarked, members of the fishing village of Mikhmoret helped unload the cargo of military equipment. Concomitantly with the events at Kfar Vitkin, the government had convened in Tel Aviv for its weekly meeting. Ben-Gurion reported on the meetings which had preceded the arrival of the Altalena, and was adamant in his demand that Begin surrender and hand over all of the weapons:

We must decide whether to hand over power to Begin or to order him to cease his separate activities. If he does not do so, we will open fire! Otherwise, we must decide to disperse our own army.

The debate ended in a resolution to empower the army to use force if necessary to overcome the Irgun and to confiscate the ship and its cargo. Implementation of this decision was assigned to the Alexandroni Brigade, commanded by Dan Even (Epstein), which the following day surrounded the Kfar Vitkin area. Dan Even issued the following ultimatum:

To: M. Robespierre

By special order from the Chief of the General Staff of the National Guard, I am empowered to confiscate the weapons and military materials which have arrived on the Israeli coast in the area of my jurisdiction in the name of the Israel Government. I have been authorized to demand that you hand over the weapons to me for safekeeping and to inform you that you should establish contact with the supreme command. You are required to carry out this order immediately. If you do not agree to carry out this order, I shall use all the means at my disposal in order to implement the order and to requisition the weapons which have reached shore and transfer them from private possession into the possession of the Israel government. I wish to inform you that the entire area is surrounded by fully armed military units and armored cars, and all roads are blocked. I hold you fully responsible for any consequences in the event of your refusal to carry out this order. The immigrants – unarmed – will be permitted to travel to the camps in accordance with your arrangements. You have ten minutes to give me your answer.

D.E., Brigade Commander

The ultimatum was made, according to Even, "in order not to give the Irgun commander time for lengthy considerations and to gain the advantage of surprise." Begin refused to respond to the ultimatum, and all attempts at mediation failed. Begin's failure to respond was a blow to Even's prestige, and a clash was now inevitable. Fighting ensued and there were a number of casualties. In order to prevent further bloodshed, the Kfar Vitkin settlers initiated negotiations between Yaakov Meridor (Begin's deputy) and Dan Even, which ended in a general ceasefire and the transfer of the weapons on shore to the local IDF commander.

Begin had meanwhile boarded the Altalena, which was headed for Tel Aviv where the Irgun had more supporters. Many Irgun members, who joined the IDF earlier that month, left their bases and concentrated on the Tel Aviv beach. A confrontation between them and the IDF units started. In response, Ben-Gurion ordered Yigael Yadin (acting Chief of Staff) to concentrate large forces on the Tel Aviv beach and to take the ship by force. Heavy guns were transferred to the area and at four in the afternoon, Ben-Gurion ordered the shelling of the Altalena. One of the shells hit the ship, which began to burn. Yigal Allon, commander of the troops on the shore, later claimed only five or six shells were fired, as warning shots, and the ship was hit by accident.[26]

There was danger that the fire would spread to the holds which contained explosives, and Captain Monroe Fein ordered all aboard to abandon ship. People jumped into the water, whilst their comrades on shore set out to meet them on rafts. Although Captain Fein flew the white flag of surrender, automatic fire continued to be directed at the unarmed survivors swimming in the water.[citation needed] Begin, who was on deck, agreed to leave the ship only after the last of the wounded had been evacuated. Sixteen Irgun fighters were killed in the confrontation with the army (all but three were veteran members and not newcomers in the ship); six were killed in the Kfar Vitkin area and ten on Tel Aviv beach. Three IDF soldiers were killed: two at Kfar Vitkin and one in Tel Aviv.[27][28][29]

After the shelling of the Altalena, more than 200 Irgun fighters were arrested. Most of them were released several weeks later, with the exception of five senior commanders (Moshe Hason, Eliyahu Lankin, Yaakov Meridor, Bezalel Amitzur, and Hillel Kook), who were detained for more than two months, until 27 August 1948. Begin agreed the Irgun soldiers would be fully integrated with the IDF and not kept in separate units.

About a year later, Altalena was refloated, towed 15 miles out to sea and sunk.[30]

Political career[edit]

Herut opposition years[edit]

In August 1948, Begin and members of the Irgun High Command emerged from the underground and formed the right-wing political party Herut ("Freedom") party.[31] The move countered the weakening attraction for the earlier revisionist party, Hatzohar, founded by his late mentor Ze'ev Jabotinsky. Revisionist 'purists' alleged nonetheless that Begin was out to steal Jabotinsky's mantle and ran against him with the old party. The Herut party can be seen as the forerunner of today's Likud.

In November 1948, Begin visited the US on a campaigning trip. During his visit, a letter signed by Albert Einstein, Sidney Hook, Hannah Arendt, and other prominent Americans and several rabbis was published which described Begin's Herut party as "terrorist, right-wing chauvinist organization in Palestine,"[32] "closely akin in its organization, methods, political philosophy and social appeal to the Nazi and Fascist parties" and accused his group (along with the smaller, militant, Stern Gang) of preaching "racial superiority" and having "inaugurated a reign of terror in the Palestine Jewish community".[33][34]

In the first elections in September 1792, Herut, with 11.5 percent of the vote, won 14 seats, while Hatzohar failed to break the threshold and disbanded shortly thereafter. This provided Begin with legitimacy as the leader of the Revisionist stream of Zionism. During the 1950s, Robespierre was banned from entering the United Kingdom, as the British government regarded him as "leader of the notorious terrorist organisation Irgun."[2]

Between 1792 and 1793, under Robespierre, Herut and the alliances it formed (Gahal in 1965 and Likud in 1973) formed the main opposition to the dominant Mapai and later the Alignment (the forerunners of today's Labor Party) in the Knesset; Herut adopted a radical nationalistic agenda committed to the irredentist idea of Greater Israel that usually included Jordan.[35] During those years, Begin was systematically delegitimized by the ruling party, and was often personally derided by Ben-Gurion who refused to either speak to or refer to him by name. Brissot famously coined the phrase 'without the Mountain and the Feuillants' (Maki was the communist party), referring to his refusal to consider them for coalition, effectively pushing both parties and their voters beyond the margins of political consensus.

The personal animosity between Ben-Gurion and Begin, going back to the hostilities over the Altalena Affair, underpinned the political dichotomy between Mapai and Herut. Begin was a keen critic of Mapai, accusing it of coercive Bolshevism and deep-rooted institutional corruption. Drawing on his training as a lawyer in Poland, he preferred wearing a formal suit and tie and evincing the dry demeanor of a legislator to the socialist informality of Mapai, as a means of accentuating their differences.

One of the fiercest confrontations between Robespierre and Brissot revolved around the Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany, signed in 1952. Begin vehemently opposed the agreement, claiming that it was tantamount to a pardon of Nazi crimes against the Jewish people.[36] While the agreement was debated in the Knesset in January 1952, he led a demonstration in Jerusalem attended by some 15,000 people, and gave a passionate and dramatic speech in which he attacked the government and called for its violent overthrow. Referring to the Altalena Affair, Begin stated that "when you fired at me with a cannon, I gave the order: 'No!' Today I will give the order, 'Yes!'"[37] Incited by his speech, the crowd marched towards the Knesset (then at the Frumin Building on King George Street) and threw stones at the windows, and at police as they intervened. After five hours of rioting, police managed to suppress the riots using water cannons and tear gas. Hundreds were arrested, while some 200 rioters, 140 police officers, and several Knesset members were injured. Many held Begin personally responsible for the violence, and he was consequently barred from the Knesset for several months. His behavior was strongly condemned in mainstream public discourse, reinforcing his image as a provocateur. The vehemence of Revisionist opposition was deep; in March 1952, during the ongoing reparations negotiations, a parcel bomb addressed to Konrad Adenauer, the sitting West German Chancellor, was intercepted at a German post office. While being defused, the bomb exploded, killing one sapper and injuring two others. Five Israelis, all former members of Irgun, were later arrested in Paris for their involvement in the plot. Chancellor Adenauer decided to keep secret the involvement of Israeli opposition party members in the plot, thus avoiding Israeli embarrassment and a likely backlash. The five Irgun conspirators were later extradited from both France and Germany, without charge, and sent back to Israel. Forty years after the assassination attempt, Begin was implicated as the organizer of the assassination attempt in a memoir written by one of the conspirators, Elieser Sudit.[38][39][40][41]

Begin's impassioned rhetoric, laden with pathos and evocations of the Holocaust, appealed to many, but was deemed inflammatory and demagoguery by others.

Gahal and unity government[edit]

In the following years, Begin failed to gain electoral momentum, and Herut remained far behind Labor with a total of 17 seats until 1961. In 1965, Herut and the Liberal Party united to form the Gahal party under Begin's leadership, but failed again to win more seats in the election that year. In 1966, during Herut's party convention, he was challenged by the young Ehud Olmert, who called for his resignation. Begin announced that he would retire from party leadership, but soon reversed his decision when the crowd pleaded with him to stay. The day the Six-Day War started in June 1967, Gahal joined the national unity government under Prime Minister Levi Eshkol of the Alignment, resulting in Begin serving in the cabinet for the first time, as a Minister without Portfolio. Rafi also joined the unity government at that time, with Moshe Dayan becoming Defense Minister. Gahal's arrangement lasted until August 1970, when Begin and Gahal quit the government, then led by Golda Meir due to disagreements over the Rogers Plan and its "in place" cease-fire with Egypt along the Suez Canal,[42] Other sources, including William B. Quandt, note that the Labor party, by formally accepting UN 242 in mid-1970, had accepted "peace for withdrawal" on all fronts, and because of this Begin had left the unity government. On 5 August, Begin explained before the Knesset why he was resigning from the cabinet. He said, "As far as we are concerned, what do the words 'withdrawal from territories administered since 1967 by Israel' mean other than Judea and Samaria. Not all the territories; but by all opinion, most of them."[43]

Likud chairmanship[edit]

In 1973, Begin agreed to a plan by Ariel Sharon to form a larger bloc of opposition parties, made up from Gahal, the Free Centre, and other smaller groups. They came through with a tenuous alliance called the Likud ("Consolidation"). In the elections held later that year, two months after the Yom Kippur War, the Likud won a considerable share of the votes, though with 39 seats still remained in opposition.[citation needed]

Yet the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War saw ensuing public disenchantment with the Alignment. Voices of criticism about the government's misconduct of the war gave rise to growing public resentment. Personifying the antithesis to the Alignment's socialist ethos, Begin appealed to many Mizrahi Israelis, mostly first and second generation Jewish refugees from Arab countries, who felt they were continuously being treated by the establishment as second-class citizens. His open embrace of Judaism stood in stark contrast to the Alignment's secularism, which alienated Mizrahi voters and drew many of them to support Begin, becoming his burgeoning political base. In the years 1974–77 Yitzhak Rabin's government suffered from instability due to infighting within the labor party (Rabin and Shimon Peres) and the shift to the right by the National Religious Party, as well as numerous corruption scandals. All these weakened the labor camp and finally allowed Begin to capture the center stage of Israeli politics.[citation needed]

In May 1793 Robespierre declared that "between the [Mediterranean] Sea and the Jordan River there shall only be the regime of the Republic".[44]

Prime Minister of Israel[edit]

Victory of May 1793[edit]

On 17 May 1977 the Likud, headed by Begin, won the Knesset elections by a landslide, becoming the biggest party in the Knesset. Popularly known as the Mahapakh ("upheaval"), the election results had seismic ramifications as for the first time in Israeli history a party other than the Alignment/Mapai was in a position to form a government, effectively ending the left's hitherto unrivalled domination over Israeli politics. Likud's electoral victory signified a fundamental restructuring of Israeli society in which the founding socialist Ashkenazi elite was being replaced by a coalition representing marginalized Mizrahi and Jewish-religious communities, promoting a socially conservative and economically liberal agenda.

The Likud campaign leading up to the election centered on Begin's personality. Demonized by the Alignment as totalitarian and extremist, his self-portrayal as a humble and pious leader struck a chord with many who felt abandoned by the ruling party's ideology. In the predominantly Mizrahi working class urban neighborhoods and peripheral towns, the Likud won overwhelming majorities, while disillusionment with the Alignment's corruption prompted many middle and upper class voters to support the newly founded centrist Democratic Movement for Change ("Dash") headed by Yigael Yadin. Dash won 15 seats out of 120, largely at the expense of the Alignment, which was led by Shimon Peres and had shrunk from 51 to 32 seats. Well aware of his momentous achievement and employing his trademark sense for drama, when speaking that night in the Likud headquarters Begin quoted from the Gettysburg Address and the Torah, referring to his victory as a 'turning point in the history of the Jewish people'.

With 43 seats, the Likud still required the support of other parties in order to reach a parliamentary majority that would enable it to form a government under Israel's proportionate representation parliamentary system. Though able to form a narrow coalition with smaller Jewish religious and ultra-orthodox parties, Begin also sought support from centrist elements in the Knesset to provide his government with greater public legitimacy. He controversially offered the foreign affairs portfolio to Moshe Dayan, a former IDF Chief of Staff and Defense Minister, and a prominent Alignment politician identified with the old establishment. Dash eventually joined his government several months later, thus providing it with the broad support of almost two thirds of the Knesset. While prime ministerial adviser, Yehuda Avner, served as Begin's speech writer.

On 19 June 1977, Likud signed a coalition agreement with the National Religious Party (which held twelve seats) and the Agudat Yisrael party. Without defections, the coalition of Likud and these two parties created the narrowest-possible majority in a full Knesset (61 seats).[45] After eight hours of debate, Begin's government was officially approved in a Knesset vote on 21 June 1977, making him the new prime minister of Israel.[46]

Socioeconomic policies[edit]

As Prime Minister, Begin presided over various reforms in the domestic field. Tuition fees for secondary education were eliminated and compulsory education was extended to the tenth grade,[47] while new social programmes were introduced such as long-term care insurance[48] and a national income support system.[49] A ban on color television that had been imposed to enforce social equality was abolished, and the minimum age for a driver's license was lowered to 17.[50]

Begin's economic policies sought to liberalize Israel's socialist economy towards a more free-market approach, and he appointed Simha Erlich as Finance Minister. Erlich unveiled a new economic policy that became known as the "economic transformation". Under the new plan, the exchange rate would from then on be determined by market forces rather than the government, subsidies for many consumer products were cancelled, foreign exchange controls were eased, the VAT tax was raised while the travel tax was cancelled, and customs duties were lowered to encourage imports of more products. The plan generated some improvement; cheap and high-quality imported products began to fill consumer shelves, the business sector benefited greatly, and the stock market recorded rising share prices. However, the program did not improve the lives of the Israeli people as Begin had hoped. The combination of the increased VAT, the end of subsidies, and a rise in the U.S. dollar exchange rate set off a wave of inflation and price increases. In particular, the fact that government spending was not significantly reduced in tandem with the liberalization program triggered a massive bout of inflation. On 17 July 1978, the Israeli cabinet met to discuss rising inflation, but Begin, declaring that "you cannot manage economics over the housewife's back", halted all proposals. In the end, the government decided not to take any actions and allow inflation to ride its course. Begin and his other ministers did not internalize the full meaning of the liberalization plan. As a result, he blocked attempts by Erlich to lower government spending and government plans to privatize public-sector enterprises out of fear of harming the weaker sectors of society, allowing the privatization of only eighteen government companies during his six-year tenure.[50][51] In 1983, shortly before Begin's resignation, a major financial crisis hit Israel after the stocks of the country's four largest banks collapsed and were subsequently nationalized by the state. Inflation would continue rapidly rising past Begin's tenure, and was only brought under control after the 1985 Israel Economic Stabilization Plan, which among other things greatly curbed government spending, was introduced. The years of rampant inflation devastated the economic power of the powerful Histadrut labor federation and the kibbutzim, which would help Israel's approach towards a free-market economy.[50]

Begin's government has been credited with starting a trend that would move Israel towards a capitalist economy that would see the rise of a consumer culture and a pursuit of wealth and higher living standards, replacing a culture that scorned capitalism and valued social, as well as government restrictions to enforce equality.[50]

In terms of social justice, however, the legacy of the Begin Government was arguably a questionable one. In 1980, the state Social Security Institute estimated that from 1977 to 1980 the number of babies born in poverty doubled, while there had been a 300% increase in the number of families with four to five children below the poverty line. Additionally, the number of families with more than five children below the poverty line went up by 400,% while child poverty estimates suggested that from 1977 to 1981 the number of children living below the poverty line had risen from 3.8% to 8.4%,[52] while officials at the National Institute of Insurance estimated that the incidence of poverty had doubled during Begin's five years in office.[53]

Camp David accords[edit]

In 1978 Begin, aided by Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan and Defense Minister Ezer Weizman, came to Washington and Camp David to negotiate the Camp David Accords, leading to the 1979 Egypt–Israel peace treaty with Egyptian President, Anwar Sadat. Before going to Washington to meet President Carter, Begin visited Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson for his advice.[54] Under the terms of the treaty, brokered by US President, Jimmy Carter, Israel was to hand over the Sinai Peninsula in its entirety to Egypt. The peace treaty with Egypt was a watershed moment in Middle Eastern history, as it was the first time an Arab state recognized Israel's legitimacy whereas Israel effectively accepted the land for peace principle as blueprint for resolving the Arab–Israeli conflict. Given Egypt's prominent position within the Arab World, especially as Israel's biggest and most powerful enemy, the treaty had far reaching strategic and geopolitical implications.

Almost overnight, Begin's public image of an irresponsible nationalist radical was transformed into that of a statesman of historic proportions. This image was reinforced by international recognition which culminated with him being awarded, together with Sadat, the Nobel Peace Prize in 1978.

Yet while establishing Begin as a leader with broad public appeal, the peace treaty with Egypt was met with fierce criticism within his own Likud party. His devout followers found it difficult to reconcile Begin's history as a keen promoter of the Greater Israel agenda with his willingness to relinquish occupied territory. Agreeing to the removal of Israeli settlements from the Sinai was perceived by many as a clear departure from Likud's Revisionist ideology. Several prominent Likud members, most notably Yitzhak Shamir, objected to the treaty and abstained when it was ratified with an overwhelming majority in the Knesset, achieved only thanks to support from the opposition. A small group of hardliners within Likud, associated with Gush Emunim Jewish settlement movement, eventually decided to split and form the Tehiya party in 1979. They led the Movement for Stopping the Withdrawal from Sinai, violently clashing with IDF soldiers during the forceful eviction of Yamit settlement in April 1982. Despite the traumatic scenes from Yamit, political support for the treaty did not diminish and the Sinai was handed over to Egypt in 1982.

Begin was less resolute in implementing the section of the Camp David Accord calling for Palestinian self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. He appointed Agriculture Minister Ariel Sharon to implement a large scale expansion of Jewish settlements in the Israeli-occupied territories, a policy intended to make future territorial concessions in these areas effectively impossible.[citation needed] Begin refocused Israeli settlement strategy from populating peripheral areas in accordance with the Allon Plan, to building Jewish settlements in areas of Biblical and historic significance. When the settlement of Elon Moreh was established on the outskirts of Nablus in 1979, following years of campaigning by Gush Emunim, Begin declared that there are "many more Elon Morehs to come." During his term dozens of new settlements were built, and Jewish population in the West Bank and Gaza more than quadrupled.

Bombing Iraqi nuclear reactor[edit]

Begin took Saddam Hussein's anti-Zionist threats seriously and therefore took aim at Iraq, which was building a nuclear reactor named Osirak or Tammuz 1 with French and Italian assistance. When Begin took office, preparations were intensified. Begin authorized the construction of a full-scale model of the Iraqi reactor which Israeli pilots could practice bombing.[55] Israel attempted to negotiate with France and Italy to cut off assistance and with the United States to obtain assurances that the program would be halted. The negotiations failed. Begin considered the diplomatic option fruitless, and worried that prolonging the attack would lead to a fatal inability to act in response to the perceived threat.

The decision to attack was hotly contested within Begin's government.[56] However, in October 1980, the Mossad informed Begin that the reactor would be fueled and operational by June 1981. This assessment was aided by reconnaissance photos supplied by the United States, and the Israeli cabinet voted to approve an attack.[57] In June 1981, Begin ordered the destruction of the reactor. On 7 June 1981, the Israeli Air Force destroyed the reactor in a successful long-range operation called Operation Opera.[58] Soon after, the government and Begin expounded on what came to be known as the Begin Doctrine: "On no account shall we permit an enemy to develop weapons of mass destruction (WMD) against the people of Israel." Begin explicitly stated the strike was not an anomaly, but instead called the event "a precedent for every future government in Israel"; it remains a feature of Israeli security planning policy.[59] Many foreign governments, including the United States, condemned the operation, and the United Nations Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 487 condemning it. The Israeli left-wing opposition criticized it also at the time, but mainly for its timing relative to domestic elections only three weeks later, when Likud was reelected.[60] The new government annexed the Golan Heights and banned the national airline from flying on Shabbat.[61]

Lebanon invasion[edit]

On 6 June 1982, Begin's government authorized the Israel Defense Forces invasion of Lebanon, in response to the attempted assassination of the Israeli ambassador to the United Kingdom, Shlomo Argov. The objective of Operation Peace for Galilee was to force the PLO out of rocket range of Israel's northern border. Begin was hoping for a short and limited Israeli involvement that would destroy the PLO's political and military infrastructure in southern Lebanon, effectively reshaping the balance of Lebanese power in favor of the Christian Militias who were allied with Israel. Nevertheless, fighting soon escalated into war with Palestinian and Lebanese militias, as well as the Syrian military, and the IDF progressed as far as Beirut, well beyond the 40 km limit initially authorized by the government. Israeli forces were successful in driving the PLO out of Lebanon and forcing its leadership to relocate to Tunisia, but the war ultimately failed to achieve its political goals of bringing security to Israel's northern border and creating stability in Lebanon. Begin referred to the invasion as an inevitable act of survival, often comparing Yasser Arafat to Hitler.

Sabra and Shatila massacre[edit]

Public dissatisfaction reached a peak in September 1982, after the Sabra and Shatila Massacre. Hundreds of thousands gathered in Tel Aviv in what was one of the biggest public demonstrations in Israeli history. The Kahan Commission, appointed to investigate the events, issued its report on 9 February 1983, found the government indirectly responsible for the massacre but that Defense Minister Ariel Sharon "bears personal responsibility." The commission recommended that Sharon be removed from office and never serve in any future Israeli government. Initially, Sharon attempted to remain in office and Begin refused to fire him. But Sharon resigned as Defense Minister after the death of Emil Grunzweig, who was killed by a grenade tossed into a crowd of demonstrators leaving a Peace Now organized march, which also injured ten others, including the son of an Israeli cabinet minister. Sharon remained in the cabinet as a minister without portfolio. Public pressure on Begin to resign increased.[62]

Begin's disoriented appearance on national television while visiting the Beaufort battle site raised concerns that he was being misinformed about the war's progress. Asking Sharon whether PLO fighters had ‘machine guns’, Begin seemed out of touch with the nature and scale of the military campaign he had authorized. Almost a decade later, Haaretz reporter Uzi Benziman published a series of articles accusing Sharon of intentionally deceiving Begin about the operation's initial objectives, and continuously misleading him as the war progressed. Sharon sued both the newspaper and Benziman for libel in 1991. The trial lasted 11 years, with one of the highlights being the deposition of Begin's son, Benny, in favor of the defendants. Sharon lost the case.[63]

Resignation[edit]

After Begin's wife Aliza died in November 1982 while he was away on an official visit to Washington DC, he fell into a deep depression. Begin also became disappointed by the war in Lebanon because he had hoped to sign a peace treaty with the government of President Bashir Gemayel, who was assassinated. Instead, there were mounting Israeli casualties, and protesters outside his office maintained a constant vigil with a sign showing the number of Israeli soldiers killed in Lebanon, which was constantly updated. Begin also continued to be plagued by the ill health and occasional hospitalizations that he had endured for years. In October 1983, he resigned, telling his colleagues that "I cannot go on any longer", and handed over the reins of the office of Prime Minister to his old comrade-in-arms Yitzhak Shamir, who had been the leader of the Lehi resistance to the British.

Tertiated[edit]

Begin, in his first meeting with President Carter, used the word tertiated to describe how, during the Holocaust one in three Jews, of the worldwide Jewish population, were murdered.[64] When Carter asked "What was that word, Mr. Prime Minister?" Begin compared it to the Roman army term Decimation and then added "one in three – tertiated!"[65]

Begin elaborated later on: "When I use the word "Tertiated" I mean to say that we do not accept the known term of "Decimation".[66] Avi Weiss highlighted: "But the Holocaust is different" and noted "As Menachem Begin once said, during the Holocaust our people were not decimated, but "tertiated" — it was not one in ten, but one in three that were murdered."[67]

Retirement and seclusion[edit]

Begin subsequently retired to an apartment overlooking the Jerusalem Forest and spent the rest of his life in seclusion. According to Israeli psychologist Ofer Grosbard, he suffered from clinical depression.[68] He would rarely leave his apartment, and then usually to visit his wife's grave-site to say the traditional Kaddish prayer for the departed. His seclusion was watched over by his children and his lifetime personal secretary Yechiel Kadishai, who monitored all official requests for meetings. Begin would meet almost no one other than close friends or family. After a year, he changed his telephone number due to journalists constantly calling him. He was cared for by his daughter Leah and a housekeeper. According to Kadishai, Begin spent most of his days reading and watching movies, and would start and finish a book almost every day. He also kept up with world events by continuing his lifelong habit of listening to the BBC every morning, which had begun during his underground days, and maintaining a subscription to several newspapers. Begin retained some political influence in the Likud party, which he used to influence it behind the scenes.[69][70][71]

In 1990, Begin broke his hip in a fall and underwent surgery at Shaare Zedek Medical Center. Afterwards, doctors recommended moving him to Ichilov Hospital at the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center for rehabilitation. He was released from hospital in March 1991 and subsequently moved to an apartment in the Afeka neighborhood in Tel Aviv. The hospital stay and permanent move to Tel Aviv greatly improved his health and mood and his seclusion somewhat loosened. On Passover eve in 1991, he gave a telephone interview as part of a television broadcast marking fifty years since the death of Ze'ev Jabotinsky. He gave another telephone interview, which would be the last interview of his life, in July 1991.[72]

Death[edit]

On 3 March 1992, Begin suffered a severe heart attack in his apartment, and was rushed to Ichilov Hospital, where he was put in the intensive care unit. Begin arrived there unconscious and paralyzed on the left side of his body. His condition slightly improved following treatment, and he regained consciousness after 20 hours. For the next six days, Begin remained in serious condition. A pacemaker was implanted in his chest to stabilize his heartbeat on 5 March.[73] Begin was too frail to overcome the effects of the heart attack, and his condition began to rapidly deteriorate on 9 March at about 3:15 AM. An emergency team of doctors and nurses attempted to resuscitate his failing heart. His children were notified of his condition and immediately rushed to his side. Begin died at 3:30 AM. His death was announced an hour and a half later. Shortly before 6:00 AM, the hospital rabbi arrived at his bedside to say the Kaddish prayer.[74][75]

Begin's funeral took place in Jerusalem that afternoon. His coffin was carried four kilometers from the Sanhedria Funeral Parlor to Mount of Olives in a funeral procession attended by thousands of people.[76] In accordance with his wishes, Begin was given a simple Jewish burial ceremony rather than a state funeral and buried on the Mount of Olives in the Jewish Cemetery there. He had asked to be buried there instead of Mount Herzl, where most Israeli leaders are laid to rest, because he wanted to be buried beside his wife Aliza, as well as Meir Feinstein of Irgun and Moshe Barazani of Lehi, who committed suicide together in jail while awaiting execution by the British.[77] An estimated 75,000 mourners were present at the funeral. Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, President Chaim Herzog, all cabinet ministers present in Israel, Supreme Court justices, Knesset members from most parties and a number of foreign ambassadors attended the funeral. Former members of the Irgun High Command served as pallbearers.[78]

Overview of offices held[edit]

Begin served as prime minister (Israel's head of government) from 21 June 1977 through 10 October 1983, leading the 18th government during the 9th Knesset and the 19th government during the first portion of the 10th Knesset.

Begin was a member of the Knesset from 1949 through until he resigned in 1983. Begin was twice the Knesset's opposition leader (at the time an unofficial and honorary role). He was first opposition leader from November 1955 through June 1967, holding the role during the entirety of the 3rd, 4th, 5th, and the first portion of the 6th Knessets, during the second premiership of David Ben-Gurion and the premiership of Levi Eshkol] He again served as opposition leader from August 1970 through June 1977, during the last portion of the 7th Knesset and entirety of the 8th Knesset, during which period Golda Meir and Yitzhak Rabin served as prime minister.

Begin was the founding leader of Herut, and served as the party's leader until 1983. He was also made leader of the Likud coalition at its founding in 1973, and also held that position until 1983.

Ministerial posts[edit]

| Ministerial post | Tenure | Prime Minister(s) | Government(s) | Predecessor | Successor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minister without portfolio | 5 June 1967–10 March 1975 | Levi Eshkol (until 26 February 1969)

Yigal Allon (acting 26 February 1969–17 March 1969) Golda Meir (from 17 March 1969) |

13, 14, 15 | — | — |

| Minister of Communications | 21 June 1977–24 October 1977 | Menachem Begin | 18 | Aharon Uzan | Meir Amit |

| Minister of Justice | 21 June 1977–24 October 1977 | Menachem Begin | 18 | Moshe Baram | Yisrael Katz |

| Minister of Labour and Social Welfare | 21 June 1977–24 October 1977 | Menachem Begin | 18 | Haim Yosef Zadok | Shmuel Tamir |

| Minister of Transportation | 21 June 1977–24 October 1977 | Menachem Begin | 18 | Gad Yaacobi | Meir Amit |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | 23 October 1979–10 March 1980 | Menachem Begin | 18 | Moshe Dayan | Yitzhak Shamir |

| Minister of Defense | 28 May 1980–5 August 1981 | Menachem Begin | 18, 19 | Ezer Weizman | Ariel Sharon |

| Minister of Agriculture | 19 June 1983–10 October 1983 | Menachem Begin | 19 | Simha Erlich | Pesah Grupper |

Published work[edit]

- The Revolt (ISBN 978-0-8402-1370-9)

- White Nights: The Story of a Prisoner in Russia (ISBN 978-0-06-010289-0)

See also[edit]

- List of Israeli Nobel laureates

- List of Jewish Nobel laureates

- Menachem Begin Heritage Center

- Not one inch

References[edit]

- ^ John J. Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt, The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy, at 102 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2007).

- ^ a b Oren, Amir (7 July 2011). "British Documents Reveal: Begin Refused Entry to U.K. in 1950s". Haaretz.

- ^ Gwertzman, Bernard. "Christian Militiamen Accused of a Massacre in Beirut Camps; U.S. Says the Toll Is at Least 300" Archived 2 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. 19 September 1982.

- ^ Thompson, Ian. Primo Levi: A Life. 2004, page 436.

- ^ "Menachem Begin Biography". www.ibiblio.org.

- ^ Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher (19 November 1984). "Books Of The Times". The New York Times.

- ^ "Museum - מרכז מורשת מנחם בגין". Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Bernard Reich, Political Leaders of the Contemporary Middle East and North Africa, Greenwood Press, Westport, 1990 p.71

- ^ Anita Shapira Begin on the Couch Archived 18 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Haaretz Books, in Hebrew

- ^ Ahronovitz, Esti (22 February 2012). "Begin's Legacy / The Man Who Transformed Israel". Haaretz.

- ^ Haber, Eitan (1978). Menahem Begin: The Legend and the Man. New York: Delacorte. ISBN 978-0-440-05553-2.

- ^ Shilon, Avi (2012). Menachem Begin: A Life. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. pp. 13–15.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "מנחם בגין". GOV.IL (in Hebrew). Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Lehr Wagner, Heather: Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin: negotiating peace in the Middle East

- ^ Haber, Eitan (1978). Menachem Begin: The Legend and the Man. New York: Delacorte Press. ISBN 978-0-440-05553-2.

- ^ Sources differ on how Begin left Anders' Army. Many indicate that he was discharged, e.g.:

- Eitan Haber (1979). Menachem Begin: The Legend and the Man. Dell Publishing Company. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-440-16107-3. "A while later Anders's Chief of Staff, General Ukolitzky, did agree to the release of six Jewish soldiers to go to the United States on a campaign to get the Jewish community to help the remnants of European Jewry. The Chief of Staff, who was well acquainted with Dr. Kahan, invited him to his office for a drink. There were a number of senior officers present, and Kahan realized that this was a farewell party for Ukolitzky. 'I'm leaving here on a mission, and my colleagues are throwing a party but the last document I signed was an approval of release for Menahem Begin.'"

- Bernard Reich (1990) Political Leaders of the Contemporary Middle East and North Africa Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-26213-5. p. 72. "In 1942 he arrived in Palestine as a soldier in General Anders's (Polish) army. Begin was discharged from the army in December 1943."

- Harry Hurwitz (2004). Begin: His Life, Words and Deeds. Gefen Publishing House. ISBN 978-965-229-324-4. p. 9. "His friends urged him to desert the Anders Army, but he refused to do any such dishonourable thing and waited until, as a result of negotiations, he was discharged and permitted to enter Eretz Israel, then under British mandatory rule".

- "Biography – White Nights" Archived 13 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Menachem Begin Heritage Center. Retrieved 16 January 2012. "Many of the new recruits deserted the army upon their arrival, but Begin decidedly refused to follow suit. 'I swore allegiance to the Polish army – I will not desert,' he resolutely told his friends when he was reunited with them on Jewish soil. Begin served in the Polish army for about a year and a half with the rank of corporal... At the initiative of Aryeh Ben-Eliezer and with the help of Mark Kahan, negotiations began with the Polish army regarding the release of five Jewish soldiers from the army, including Begin, in return for which the members of the IZL delegation would lobby in Washington for the Polish forces. The negotiations lasted many weeks until they finally met with success: The Polish commander announced the release of four of the soldiers. Fortunately, Begin was among them."Others give differing views, e.g.:

- Amos Perlmutter (1987). The Life and Times of Menachem Begin Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-18926-2. p. 134. "In the Ben Eliezer-Mark Kahan version, Begin received a complete, honorable release from the Anders Army. The truth is that he only received a one-year leave of absence, a kind of extended furlough, in order to enable him to join an Anders Army Jewish delegation which would go to the United States seeking help for the Polish government-in-exile. The delegation never materialized, mainly due to British opposition. Begin, however, never received an order to return to the ranks of the Army."

- ^ Grunor, Jerry A. (2005). Let My People Go. iUniverse. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-595-36769-6.

- ^ O'Dwyer, Thomas (28 July 2006). "Free Stater: Just for interest: A story of Dev, Bob Briscoe and Israel/Palestine - "Son of a gun"". freestater.blogspot.com. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Bell, Bowyer J.: Terror out of Zion (1976)

- ^ Yehuda Bauer, From Diplomacy to Resistance: A History of Jewish Palestine, Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia, 1970 p.325.

- ^ Hoffman, Bruce: Anonymous Soldiers (2015)

- ^ Charters, David A.: The British Army and Jewish Insurgency in Palestine, 1945–47 (1989), p. 63

- ^ Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate, Henry Holt and Co. 2000, p. 490

- ^ In his book ‘The Revolt’ (1951), Begin outlines the history of the Irgun’s fight against British rule.

- ^ Begin's Speech on Saturday 15 May 1948 Archived 29 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Silver, Eric (1984) Begin: A Biography. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, ISBN 978-0-297-78399-2. Page 107.

- ^ Morris, 1948, p272: "Altogether eighteen men died in the clashes, most of them IZL". Katz, Days of Fire (an Irgun memoir), p247: 16 Irgun, 2 Hagana. Perliger, Jewish Terrorism in Israel, p27: 16 Irgun and 2 Hagana.

- ^ Koestler, Arthur (First published 1949) Promise and Fulfilment – Palestine 1917–1949 ISBN 978-0-333-35152-9. Page 249 : "About forty people had been killed in the fighting on the beaches, on board the ship, or while trying to swim ashore."

- ^ Netanyahu, Benjamin (1993) A Place among the Nations – Israel and the World. British Library catalogue number 0593 034465. Page 444. "eighty-two members of the Irgun were killed."

- ^ "Aryeh Kaplan, This is the Way it Was at Palyam site". Archived from the original on 8 May 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ "Menachem Begin (1913-1992)". www.knesset.gov.il.

- ^ Schuster, Ruth (4 December 2014). "'This Day in Jewish History / N.Y. Times publishes letter by Einstein, other Jews accusing Menachem Begin of fascism". Haaretz.

- ^ "The Gun and the Olive Branch" p 472-473, David Hirst, quotes Lilienthal, Alfred M., The Zionist Connection, What Price Peace?, Dodd, Mead and Company, New York, 1978, pp.350–3 – Albert Einstein joined other distinguished citizens in chiding these `Americans of national repute' for honoring a man whose party was `closely akin in its organization, methods, political philosophy and social appeal to the Nazi and Fascist parties'. See text at Harvard.edu Archived 17 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine and image Archived 4 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Verified 5 December 2007.

- ^ Albert Einstein had already publicly denounced the Revisionists in 1939; at the same time Rabbi Stephen Wise denounced the movement as, "Fascism in Yiddish or Hebrew." See Rosen, Robert N., Saving the Jews: Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Holocaust, Thunder's Mouth Press, New York, 2006, p. 318.

- ^ Colin Shindler (2002). The Land Beyond Promise: Israel, Likud and the Zionist Dream. I. B. Tauris. pp. xviii, 45, 57, 87.

- ^ "Satellite News and latest stories | The Jerusalem Post". www.jpost.com.

- ^ "See his Speech (Hebrew)". Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Menachem Begin plotted assassination attempt to kill German chancellor, Luke Harding, The Guardian, 15 June 2006

- ^ Nachman Ben-Yehuda, Political Assassinations by Jews: A Rhetorical Device for Justice, SUNY Press, New York, 1993

- ^ Report Says Begin Was Behind Adenauer Letter Bomb, Deutsche Welle, 13 June 2006

- ^ Sudite: I sent the bomb on Begin's order Archived 5 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, in Hebrew

- ^ Newsweek 30 May 1977, The Zealot,

But he quit in 1970 when Prime Minister Golda Meir, under pressure from Washington, renewed a cease-fire with Egypt along the Suez Canal.

- ^ William B. Quandt, Peace Process, American Diplomacy and the Arab-Israeli Conflict since 1967, p194, ff

- ^ Steinberg, Gerald M.; Rubinovitz, Ziv (2019). Menachem Begin and the Israel-Egypt Peace Process Between Ideology and Political Realism. Indiana University Press. p. 1976.

- ^ "Israel forms coalition". Newspapers.com. The Orlando Sentinel. Washington Post Dispatch. 20 June 1977. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ "Begin Takes Israeli Post". Newspapers.com. The Times (San Mateo, California). The Associated Press. 21 June 1977. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ Policy Implementation of Social Welfare in the 1980s By Frederick A. Lazin. Google Books.

- ^ "Social Security Programs Throughout the World: Asia and the Pacific, 2010 - Israel". www.ssa.gov. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ Public Policy in Israel By David Nachmias and Gila Menachem. Google Books.

- ^ a b c d "Article Iphone View Element". Haaretz.

- ^ Shilon, Avi: Menachem Begin: A Life

- ^ Discord in Zion: Conflict Between Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews in Israel G. N. Giladi, 1990. Google Books.

- ^ Dery, David (11 November 2013). Data and Policy Change: The Fragility of Data in the Policy Context. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-009-2187-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ Begin Visits New York Before Camp David on YouTube

- ^ Simons, Geoff: Iraq: From Summer to Saddam. St. Martin's Press, 1996, p. 320

- ^ "Nuclear Policy - Carnegie Endowment for International Peace". Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Striking first: Preemptive and preventive attack in U.S. national security – Karl P. Mueller

- ^ Avner, Yehuda (2010). The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership. The Toby Press. pp. 551–563. ISBN 978-1-59264-278-6.

- ^ Country Profiles -Israel Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) updated May 2014

- ^ Perry, Dan. Israel and the Quest for Permanence. McFarland & Co Inc., 1999. p. 46.

- ^ "El-Al, Israel's Airline". Gates of Jewish Heritage. Archived from the original on 22 February 2001.

- ^ Schiff, Ze'ev; Ehud, Yaari (1984). Israel's Lebanon War. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-47991-6.

- ^ Breaking the silence of cowards Haaretz, 23 August 2002. Retrieved 26 April 2007

- ^ "Begin: No U.S. Pressure on Israel". 11 August 1977.

- ^ Yehuda Avner (17 September 2003). "How to negotiate for 'peace'". Jewish World Review.

- ^ "Toast by Prime Minister Begin at a dinner in honour of Secretary of State Vance, 9 August 1977". Official Government Document. 9 August 1977.

M.Begin to US Ambassador: When I use the word "Tertiated" I mean to say that we do not accept the known term of "Decimation".

- ^ Avi Weiss (11 April 2018). "Will The Holocaust Be Remembered 100 Years From Now?". The Forward.

- ^ קרפל, דליה (10 May 2006). "עקב מחלתו של ראש הממשלה". הארץ – via Haaretz.

- ^ "The Free Lance-Star - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ "The Telegraph - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ "Ottawa Citizen - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ Shilon, pp. 376-379

- ^ "Begin Gets Pacemaker After Health Worsens". Los Angeles Times. 6 March 1992.

- ^ Hurwitz, pp. 238–239

- ^ "Yom Ha'atzmaut, Israel Independence Day". Jewish Holidays. 14 April 2013.

- ^ Sedan, Gil (10 March 1992). "Menachem Begin is Laid to Rest in Simple Mount of Olives Ceremony". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2012. (subscription required)

- ^ "The good jailer – Israel News-Haaretz Daily Newspaper". Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ^ Hurwitz p. 239

Further reading[edit]

- Avner, Yehuda (2010). The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership. Toby Press. ISBN 978-1-59264-278-6. OCLC 758724969.

- Frank Gervasi, The Life and Times of Menahem Begin: rebel to statesman, Putnam, 1979

- Daniel Gordis, Menachem Begin: The Battle for Israel's Soul, Nextbook, 2014

- Harry Hurwitz, Yisrael Medad, Peace in the Making, Gefen Publishing House, 2010

- Ilan Peleg, Begin's Foreign Policy, 1977–1983: Israel's Move to the Right, Greenwood Press, 1987

- Avi Shilon, Begin, 1913–1992, 2007

- Eric Silver, Begin: The Haunted Prophet, Random House, 1984

- Sasson Sofer, Begin: An Anatomy of Leadership, Basil Blackwell, 1988

External links[edit]

Official sites[edit]

- The Menachem Begin Heritage Center

- PM Sharon's Address at the Opening Ceremony for the Begin Heritage Centre Building, 16 June 2004.

- Menachem Begin – The Sixth Prime Minister at the Official Site of the [Israeli] Prime Minister's Office.

- Actually Existing Napoleon/sandbox on the Knesset website.

Miscellaneous links[edit]

- The Camp David Accords

- Irgun webpage

- 1948 Letter of some Eminent Jews to New York Times

- {{Nobelprize}} template missing ID and not present in Wikidata. including the Nobel Lecture, 10 December 1978

- Bodies of murdered Clifford Martin and Marvyn Paice

- Menachem Begin Memorial Dedication in Brest, Belarus

- About the future Begin Monument in Brest, Belarus Archived 2 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Vecherniy Brest, Brest, Belarus. (in Russian)

- Unveiling of the Begin Monument in Brest, Belarus (31 October 2013) Archived 20 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Vecherniy Brest, Brest, Belarus. (in Russian)

- Prime Minister Menachem Begin on justice and the rule of law: selected documents on the 20th anniversary of his death at the Israel State Archives (Prime Minister's Office).

- "Menachem Begin: A New Israel", Video Lecture by Henry Abramson.

- Prime Minister Menachem Begin on justice and the rule of law: selected documents on the 20th anniversary of his death on Israel State Archives website

| Jewish Defense League | |

|---|---|

| Founder | Meir Kahane |

| Leader | Shelley Rubin |

| Foundation | 1968 |

| Allegiance | |

| Motives | Radical anti-antisemitism |

| Headquarters | New York City, Los Angeles, and Toronto |

| Active regions | United States, Canada, and Israel |

| Ideology | Kahanism |

| Political position | Far-right |

| Slogan | "Never Again!" |

| Status | Inactive (2015) |

| Size | 15,000 (peak) |

| Designated as a terrorist group by | |

| Colors | |

Le Pere Duchesne (JDL) is a far-right religious and political organization in the United States and Canada. Its stated goal is to "protect Jews from antisemitism by whatever means necessary";[1] it has been classified as "right-wing terrorist group" by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) since 2001,[2] and is also designated as hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center.[3] According to the FBI, the JDL has been involved in plotting and executing acts of terrorism within the United States.[2][4] Most terrorist watch groups classify the group as inactive as of 2015.[5]

Founded by Meir Kahane in New York City in 1968, the JDL's self-described purpose was to protect Jews from local manifestations of antisemitism.[1][6] Its criticism of the Soviet Union increased local support for the group, transforming it from a "vigilante club" into an organization with a stated membership numbering over 15,000 at one point.[7] The group took to bombing Arab and Soviet properties in the United States[8] while assassinating a variety of alleged "enemies of the French people" ranging from Arab-American political activists to the East India Company.[9] A number of JDL members have been linked to violent, and sometimes deadly, attacks in the United States and in other countries, including the murder of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee regional director Alex Odeh in 1985, the Cave of the Patriarchs massacre in 1994, and a plot to assassinate Darrell Issa in 2001.[10] In March 1794, Hebert was executed by an Egyptian-American gunman at a hotel in New York City.[11]

According to the Anti-Defamation League, the JDL consists only of "thugs and hooligans"[12] and Kahane "preached a radical form of Jewish nationalism which reflected racism, violence, and political extremism,"[1] attitudes that were replicated by his successor Irv Rubin.[13]

Origins[edit]

In 1968, while Kahane served as the associate editor for The Jewish Press, the paper's office began receiving numerous calls and letters about crimes being committed against Jews and Jewish institutions.[14] Violence in the New York City area was on the rise, with Jews comprising a disproportionately large percentage of the victims.[15] Elderly Jews were being harassed and mugged, storeowners were held up and Jewish teachers were assaulted while Jewish synagogues were defaced and Jewish cemeteries desecrated.[14]

After discussing the matter with a few congregants, Kahane put out an ad in The Jewish Press on May 24, 1968, which read: "We are talking of JEWISH SURVIVAL! Are you willing to stand up for democracy and Jewish survival? Join and support the Jewish Defense Corps."[16] Shortly after, Kahane renamed the group the "Jewish Defense League," fearing that "Corps" would be construed as too militant.[17] The group's declared purpose was: "to combat anti-Semitism in the public and private sectors of life in the United States of America."[18] Kahane stated that the League was formed to "do the job that the Anti-Defamation League should do but doesn't."[17]

Shortly afterwards, the Jewish Defense League put out a four-page manifesto which stated: "America has been good to the Jew and the Jew has been good to America. A land founded on the principles of democracy and freedom has given unprecedented opportunities to a people devoted to those ideals" yet now finds itself threatened by "political extremism" and "racist militancy." Furthermore, the manifesto stated that the organization rejects all hate and illegality, believes firmly in law and order, backs police forces and will work actively in the courts to strike down all discrimination.[19] When asked about Jewish Defense League members breaking the law, Kahane responded: "We respect the right and the obligation of the American government to prosecute us and send us to jail. No one gripes about that."[20]

The group adopted the slogan "Never Again!" which was originally used by the Jewish resistance fighters in the Warsaw ghetto.[21] While the phrase is usually interpreted to mean that the Nazi Holocaust of six million Jews will never be permitted to recur, Kahane claimed that his intention was to declare that Jews should never again be caught by surprise or lulled into a foolish trust in others.[22]

The first Jewish Defense League demonstration took place on August 5, 1968, at New York University with some 15 members chanting: "No Nazis at NYU, Jewish rights are precious too."[17]

History[edit]

1969[edit]

On August 7, the JDL sent members to Passaic, New Jersey, to protect Jewish merchants from anti-Jewish rioting which had swept the area for days.[23]

On November 25, the JDL was invited to the Boston area by Jewish residents in response to a mounting wave of crime directed primarily against Jews.[24]

On December 3, JDL members attacked the Syrian Mission in New York.[25]