User:392MetabolicEditor/sandbox

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

5,7-Dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)chroman-4-one

| |

| Other names

Naringetol; Salipurol; Salipurpol; 4',5,7-Trihydroxyflavanone

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C15H12O5 | |

| Molar mass | 272.256 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 251 °C (484 °F; 524 K)[1] |

| 475 mg/L[1] | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

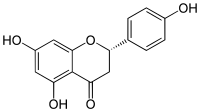

Naringenin, a bitter[2], colourless substance[3], is a flavanone, a type of flavonoid. It is the predominant flavanone in grapefruit[4], and is found in a variety of fruits and herbs.[5]

Structure[edit]

Naringenin has the skeleton structure of a flavanone with three hydroxy groups at the 4', 5, and 7 carbons. It may be found both in the aglycol form, naringenin, or in its glycosidic form, naringin, which has the addition of the disaccharide neohesperidose attached via a glycosidic linkage at carbon 7.

Chirality[edit]

Like the majority of flavanones, naringenin has a single chiral center at carbon 2, resulting in enantiomeric forms of the compound.[6] The enantiomers are found in varying ratios in natural sources.[7] Racemization of S(-)-naringenin has been shown to occur fairly quickly.[8] Naringenin has been shown to be resistant to enatiomerization over pH 9-11. [9]

Separation and analysis of the enantiomers has been explored for over 20 years,[10] primarily via high-performance liquid chromatography on polysaccharide-derived chiral stationary phases. [11][12][13][14] There is evidence to suggest stereospecific pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics profiles, which has been proposed to be an explanation for the wide variety in naringenin's reported bioactivity. [7]

Sources[edit]

Naringenin and its glycoside has been found in a variety of herbs and fruits, including grapefruit[15],bergamot[16], sour orange[17], tart cherries[18], tomatoes [19][20], cocoa[21], Greek oregano[22], water mint [23], as well as in beans[24]. Ratios of naringenin to naringin vary among sources[19], as do enantiomeric ratios.[7]

Bioavailability[edit]

This bioflavonoid is difficult to absorb on oral ingestion. In the best-case scenario, only 15% of ingested naringenin will get absorbed in the human gastrointestinal tract. [citation needed]

The naringenin-7-glucoside form seems less bioavailable than the aglycol form.[25]

Grapefruit juice can provide much higher plasma concentrations of naringenin than orange juice.[26] Also found in grapefruit is the related compound kaempferol, which has a hydroxyl group next to the ketone group.

Naringenin can be absorbed from cooked tomato paste.[27]

Metabolism[edit]

The enzyme naringenin 8-dimethylallyltransferase uses dimethylallyl diphosphate and (−)-(2S)-naringenin to produce diphosphate and 8-prenylnaringenin.

Biodegradation[edit]

Cunninghamella elegans, a fungal model organism of the mammalian metabolism, can be used to study the naringenin sulfation.[28]

Potential biological effects[edit]

Inhibitory Activity[edit]

Effect on Cytochrome P450[edit]

Naringenin has been shown to have an inhibitory effect on the human cytochrome P450 isoform CYP1A2, which can change pharmacokinetics in a human (or orthologous) host of several popular drugs in an adverse manner, even resulting in carcinogens of otherwise harmless substances.[29] The National Research Institute of Chinese Medicine in Taiwan conducted experiments on the effects of the grapefruit flavanones naringin and naringenin on CYP450 enzyme expression. Naringenin proved to be a potent inhibitor of the benzo(a)pyrene metabolizing enzyme benzo(a)pyrene hydroxylase (AHH) in experiments in mice.[30]

Antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral[edit]

Naringenin's potential antibacterial and antifungal behaviour has been investigated. In 1987, it was reported that naringenin had no antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus epidermidis.[31] This finding was not replicated in a 2000 study in which naringenin was shown to indeed have an antimicrobial effect on S. epidermidis, as well as Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Micrococcus luteus, and Escherichia coli.[32] Further research has added evidence for antimicrobial effects against Lactococcus lactis[33], lactobacillus acidophilus, Actinomyces naeslundii, Prevotella oralis, Prevotella melaninogencia, Porphyromonas gingivalis [34], as well as yeasts such as Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, and Candida krusei[35]. There is also evidence of antibacterial effects on H. pylori, though naringenin has not been shown to have any inhibition on urease activity of the microbe[36].

Naringenin has also been shown to reduce hepatitis C virus production by infected hepatocytes (liver cells) in cell culture. This seems to be secondary to naringenin's ability to inhibit the secretion of very-low-density lipoprotein by the cells.[37] The antiviral effects of naringenin are currently under clinical investigation.[38] Reports of antiviral effects on polioviruses HSV-1 and HSV-2 have also been made, though replication of the viruses has not been inhibited.[39][40][41]

Anti-inflamatory[edit]

Despite evidence of anti-inflammatory activity of naringin[42], the anti-inflammatory activity of naringenin has been observed to be poor to nonexistent.[43][44]

Antioxidant[edit]

Naringenin has been shown to have significant antioxidant properties.[45][46]

Naringenin has also been shown to reduce oxidative damage to DNA in vitro and in animal studies.[47][48]

Anticancer[edit]

Cytotoxicity has been induced reportedly by naringenin in cancer cells from breast, stomach, liver, cervix, pancreas, and colon tissues, along with leukaemia cells.[49] The mechanisms behind inhibition of human breast carcinoma growth have been examined, and two theories have been proposed.[50] The first theory is that naringenin inhibits aromatase, thus reducing growth of the tumor.[51] The second mechanism proposes that interactions with estrogen receptors is the cause behind the modulation of growth. [52]

Antiadipogenic Activity and Cardioprotective Effects[edit]

Naringenin has been reported to induce apoptosis in preadipocytes.[53]

Naringenin seems to protect LDLR-deficient mice from the obesity effects of a high-fat diet.[54]

Naringenin lowers the plasma and hepatic cholesterol concentrations by suppressing HMG-CoA reductase and ACAT in rats fed a high-cholesterol diet.[55]

Other Effects[edit]

Naringenin also produces BDNF-dependent antidepressant-like effects in mice.[56]

In 2006 it was shown to increase the mRNA expression levels of two DNA repair enzymes, DNA pol beta and OGG1, specifically in prostate cancer cells.[57]

Like many other flavonoids, naringenin has been found to possess weak activity at the opioid receptors.[58] It specifically acts as a non-selective antagonist of all three opioid receptors, albeit with weak affinity.[58]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Naringenin". ChemIDplus.

- ^ Esaki, Sachiko; Nishiyama, Kiyotoshi; Sugiyama, Naoko; Nakajima, Ryuta; Takao, Yoshihiro; Kamiya, Shintaro (1994-01-01). "Preparation and Taste of Certain Glycosides of Flavanones and of Dihydrochalcones". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 58 (8): 1479–1485. doi:10.1271/bbb.58.1479. ISSN 0916-8451. PMID 7765281.

- ^ Shin, W.; Kim, S.; Chun, K. S. (1987-10-15). "Structure of (R,S)-hesperetin monohydrate". Acta Crystallographica Section C Crystal Structure Communications. 43 (10): 1946–1949. doi:10.1107/s0108270187089510. ISSN 0108-2701.

- ^ Felgines C, Texier O, Morand C, Manach C, Scalbert A, Régerat F, Rémésy C (December 2000). "Bioavailability of the flavanone naringenin and its glycosides in rats". Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 279 (6): G1148–54. PMID 11093936.

- ^ Yáñez, Jaime A.; Andrews, Preston K.; Davies, Neal M. (2007-04-01). "Methods of analysis and separation of chiral flavonoids". Journal of Chromatography. B, Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences. 848 (2): 159–181. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.10.052. ISSN 1570-0232. PMID 17113835.

- ^ Yáñez, Jaime A.; Andrews, Preston K.; Davies, Neal M. (2007-04-01). "Methods of analysis and separation of chiral flavonoids". Journal of Chromatography B. 848 (2): 159–181. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.10.052.

- ^ a b c Yáñez, Jaime A.; Remsberg, Connie M.; Miranda, Nicole D.; Vega-Villa, Karina R.; Andrews, Preston K.; Davies, Neal M. (2008-01-01). "Pharmacokinetics of selected chiral flavonoids: hesperetin, naringenin and eriodictyol in rats and their content in fruit juices". Biopharmaceutics & Drug Disposition. 29 (2): 63–82. doi:10.1002/bdd.588. ISSN 1099-081X.

- ^ Krause, M.; Galensa, R. (1991-07-01). "Analysis of enantiomeric flavanones in plant extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography on a cellulose triacetate based chiral stationary phase". Chromatographia. 32 (1–2): 69–72. doi:10.1007/BF02262470. ISSN 0009-5893.

- ^ Wistuba, Dorothee; Trapp, Oliver; Gel-Moreto, Nuria; Galensa, Rudolf; Schurig, Volker (2006-05-01). "Stereoisomeric Separation of Flavanones and Flavanone-7-O-glycosides by Capillary Electrophoresis and Determination of Interconversion Barriers". Analytical Chemistry. 78 (10): 3424–3433. doi:10.1021/ac0600499. ISSN 0003-2700.

- ^ Yáñez, Jaime A.; Andrews, Preston K.; Davies, Neal M. (2007-04-01). "Methods of analysis and separation of chiral flavonoids". Journal of Chromatography B. 848 (2): 159–181. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.10.052.

- ^ Krause, M.; Galensa, R. (1991-07-01). "Analysis of enantiomeric flavanones in plant extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography on a cellulose triacetate based chiral stationary phase". Chromatographia. 32 (1–2): 69–72. doi:10.1007/BF02262470. ISSN 0009-5893.

- ^ Krause, Martin; Galensa, Rudolf. "High-performance liquid chromatography of diastereomeric flavanone glycosides in Citrus on a β-cyclodextrin-bonded stationary phase (Cyclobond I)". Journal of Chromatography A. 588 (1–2): 41–45. doi:10.1016/0021-9673(91)85005-z.

- ^ Gaggeri, Raffaella; Rossi, Daniela; Collina, Simona; Mannucci, Barbara; Baierl, Marcel; Juza, Markus (2011-08-12). "Quick development of an analytical enantioselective high performance liquid chromatography separation and preparative scale-up for the flavonoid Naringenin". Journal of Chromatography A. 1218 (32): 5414–5422. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2011.02.038.

- ^ Wan, Lili; Sun, Xipeng; Li, Yan; Yu, Qi; Guo, Cheng; Wang, Xiangwei (2011-04-01). "A Stereospecific HPLC Method and Its Application in Determination of Pharmacokinetics Profile of Two Enantiomers of Naringenin in Rats". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 49 (4): 316–320. doi:10.1093/chrsci/49.4.316. ISSN 0021-9665.

- ^ Ho, Ping C; Saville, Dorothy J; Coville, Peter F; Wanwimolruk, Sompon (2000-04-01). "Content of CYP3A4 inhibitors, naringin, naringenin and bergapten in grapefruit and grapefruit juice products". Pharmaceutica Acta Helvetiae. 74 (4): 379–385. doi:10.1016/S0031-6865(99)00062-X.

- ^ Gattuso, Giuseppe; Barreca, Davide; Gargiulli, Claudia; Leuzzi, Ugo; Caristi, Corrado (2007-08-03). "Flavonoid Composition of Citrus Juices". Molecules. 12 (8): 1641–1673. doi:10.3390/12081641.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Gel-Moreto, Nuria; Streich, René; Galensa, Rudolf (2003-08-01). "Chiral separation of diastereomeric flavanone-7-O-glycosides in citrus by capillary electrophoresis". Electrophoresis. 24 (15): 2716–2722. doi:10.1002/elps.200305486. ISSN 0173-0835. PMID 12900888.

- ^ Wang, H.; Nair, M. G.; Strasburg, G. M.; Booren, A. M.; Gray, J. I. (1999-03-01). "Antioxidant polyphenols from tart cherries (Prunus cerasus)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 47 (3): 840–844. ISSN 0021-8561. PMID 10552377.

- ^ a b Minoggio, M.; Bramati, L.; Simonetti, P.; Gardana, C.; Iemoli, L.; Santangelo, E.; Mauri, P. L.; Spigno, P.; Soressi, G. P. (2003-01-01). "Polyphenol pattern and antioxidant activity of different tomato lines and cultivars". Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism. 47 (2): 64–69. doi:69277. ISSN 0250-6807. PMID 12652057.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help) - ^ Vallverdú-Queralt, A; Odriozola-Serrano, I; Oms-Oliu, G; Lamuela-Raventós, RM; Elez-Martínez, P; Martín-Belloso, O (2012). "Changes in the polyphenol profile of tomato juices processed by pulsed electric fields". J Agric Food Chem. 60 (38): 9667–9672. doi:10.1021/jf302791k. PMID 22957841.

- ^ Sánchez-Rabaneda, Ferran; Jáuregui, Olga; Casals, Isidre; Andrés-Lacueva, Cristina; Izquierdo-Pulido, Maria; Lamuela-Raventós, Rosa M. (2003-01-01). "Liquid chromatographic/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometric study of the phenolic composition of cocoa (Theobroma cacao)". Journal of mass spectrometry: JMS. 38 (1): 35–42. doi:10.1002/jms.395. ISSN 1076-5174. PMID 12526004.

- ^ Exarchou, Vassiliki; Godejohann, Markus; van Beek, Teris A.; Gerothanassis, Ioannis P.; Vervoort, Jacques (2003-11-01). "LC-UV-Solid-Phase Extraction-NMR-MS Combined with a Cryogenic Flow Probe and Its Application to the Identification of Compounds Present in Greek Oregano". Analytical Chemistry. 75 (22): 6288–6294. doi:10.1021/ac0347819. ISSN 0003-2700.

- ^ Olsen, Helle T.; Stafford, Gary I.; van Staden, Johannes; Christensen, Søren B.; Jäger, Anna K. (2008-05-22). "Isolation of the MAO-inhibitor naringenin from Mentha aquatica L." Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 117 (3): 500–502. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2008.02.015.

- ^ Hungria, M.; Johnston, A. W.; Phillips, D. A. (1992-05-01). "Effects of flavonoids released naturally from bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) on nodD-regulated gene transcription in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. phaseoli". Molecular plant-microbe interactions: MPMI. 5 (3): 199–203. ISSN 0894-0282. PMID 1421508.

- ^ Choudhury R, Chowrimootoo G, Srai K, Debnam E, Rice-Evans CA (November 1999). "Interactions of the flavonoid naringenin in the gastrointestinal tract and the influence of glycosylation". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 265 (2): 410–5. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.1695. PMID 10558881.

- ^ Erlund I, Meririnne E, Alfthan G, Aro A (February 2001). "Plasma kinetics and urinary excretion of the flavanones naringenin and hesperetin in humans after ingestion of orange juice and grapefruit juice". J. Nutr. 131 (2): 235–41. PMID 11160539.

- ^ Bugianesi R, Catasta G, Spigno P, D'Uva A, Maiani G (November 2002). "Naringenin from cooked tomato paste is bioavailable in men". J. Nutr. 132 (11): 3349–52. PMID 12421849.

- ^ Ibrahim AR (January 2000). "Sulfation of naringenin by Cunninghamella elegans". Phytochemistry. 53 (2): 209–12. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00487-2. PMID 10680173.

- ^ Fuhr U, Klittich K, Staib AH (April 1993). "Inhibitory effect of grapefruit juice and its bitter principal, naringenin, on CYP1A2 dependent metabolism of caffeine in man". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 35 (4): 431–6. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(96)00417-1. PMC 1381556. PMID 8485024.

- ^ Ueng YF, Chang YL, Oda Y, Park SS, Liao JF, Lin MF, Chen CF (1999). "In vitro and in vivo effects of naringin on cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenase in mouse liver". Life Sci. 65 (24): 2591–602. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00528-7. PMID 10619367.

- ^ Nishino, Chikao; Enoki, Nobuyasu; Tawata, Shinkichi; Mori, Akihisa; Kobayashi, Koji; Fukushima, Masako (1987-01-01). "Antibacterial Activity of Flavonoids against Staphylococcus epidermidis, a Skin Bacterium". Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 51 (1): 139–143. doi:10.1080/00021369.1987.10867965. ISSN 0002-1369.

- ^ Rauha, Jussi-Pekka; Remes, Susanna; Heinonen, Marina; Hopia, Anu; Kähkönen, Marja; Kujala, Tytti; Pihlaja, Kalevi; Vuorela, Heikki; Vuorela, Pia (2000-05-25). "Antimicrobial effects of Finnish plant extracts containing flavonoids and other phenolic compounds". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 56 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00218-X.

- ^ Mandalari, G.; Bennett, R. N.; Bisignano, G.; Trombetta, D.; Saija, A.; Faulds, C. B.; Gasson, M. J.; Narbad, A. (2007-12-01). "Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids extracted from bergamot (Citrus bergamia Risso) peel, a byproduct of the essential oil industry". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 103 (6): 2056–2064. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03456.x. ISSN 1364-5072. PMID 18045389.

- ^ Koru, Ozgur; Toksoy, Fulya; Acikel, Cengiz Han; Tunca, Yasar Meric; Baysallar, Mehmet; Uskudar Guclu, Aylin; Akca, Eralp; Ozkok Tuylu, Asli; Sorkun, Kadriye (2007-06-01). "In vitro antimicrobial activity of propolis samples from different geographical origins against certain oral pathogens". Anaerobe. 13 (3–4): 140–145. doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2007.02.001. ISSN 1075-9964. PMID 17475517.

- ^ Uzel, Ataç; Sorkun, Kadri˙ye; Önçağ, Özant; Çoğulu, Dilşah; Gençay, Ömür; Sali˙h, Beki˙r (2005-04-25). "Chemical compositions and antimicrobial activities of four different Anatolian propolis samples". Microbiological Research. 160 (2): 189–195. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2005.01.002.

- ^ Bae, Eun-Ah; Han, Myung; Kim, Dong-Hyun. "In vitroAnti-Helicobacter pylori Activity of Some Flavonoids and Their Metabolites". Planta Medica. 65 (05): 442–443. doi:10.1055/s-2006-960805.

- ^ Nahmias Y, Goldwasser J, Casali M, van Poll D, Wakita T, Chung RT, Yarmush ML (May 2008). "Apolipoprotein B-dependent hepatitis C virus secretion is inhibited by the grapefruit flavonoid naringenin". Hepatology. 47 (5): 1437–45. doi:10.1002/hep.22197. PMID 18393287.

- ^ A Pilot Study of the Grapefruit Flavonoid Naringenin for HCV Infection

- ^ Mucsi, I.; Prágai, B. M. (1985-07-01). "Inhibition of virus multiplication and alteration of cyclic AMP level in cell cultures by flavonoids". Experientia. 41 (7): 930–931. doi:10.1007/BF01970018. ISSN 0014-4754.

- ^ Lyu, Su-Yun; Rhim, Jee-Young; Park, Won-Bong (2005-11-01). "Antiherpetic activities of flavonoids against herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2)in vitro". Archives of Pharmacal Research. 28 (11): 1293–1301. doi:10.1007/BF02978215. ISSN 0253-6269.

- ^ Castrillo, JoséLuis; Berghe, Dirk Vanden; Carrasco, Luis. "3-methylquercetin is a potent and selective inhibitor of poliovirus RNA synthesis". Virology. 152 (1): 219–227. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(86)90386-7.

- ^ "Suppression of Infection-Induced Endotoxin Shock in Mice by aCitrusFlavanone Naringin". Planta Medica. 70 (1): 17–22. doi:10.1055/s-2004-815449.

- ^ Gutiérrez-Venegas, Gloria; Kawasaki-Cárdenas, Perla; Rita Arroyo-Cruz, Santa; Maldonado-Frías, Silvia (2006-07-10). "Luteolin inhibits lipopolysaccharide actions on human gingival fibroblasts". European Journal of Pharmacology. 541 (1–2): 95–105. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.03.069.

- ^ Olszanecki, R.; Gebska, A.; Kozlovski, V. I.; Gryglewski, R. J. (2002-12-01). "Flavonoids and nitric oxide synthase". Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology: An Official Journal of the Polish Physiological Society. 53 (4 Pt 1): 571–584. ISSN 0867-5910. PMID 12512693.

- ^ Gorinstein, Shela; Leontowicz, Hanna; Leontowicz, Maria; Krzeminski, Ryszard; Gralak, Mikolaj; Delgado-Licon, Efren; Martinez Ayala, Alma Leticia; Katrich, Elena; Trakhtenberg, Simon (2005-04-01). "Changes in Plasma Lipid and Antioxidant Activity in Rats as a Result of Naringin and Red Grapefruit Supplementation". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (8): 3223–3228. doi:10.1021/jf058014h. ISSN 0021-8561.

- ^ Yu, Jun; Wang, Limin; Walzem, Rosemary L.; Miller, Edward G.; Pike, Leonard M.; Patil, Bhimanagouda S. (2005-03-01). "Antioxidant Activity of Citrus Limonoids, Flavonoids, and Coumarins". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (6): 2009–2014. doi:10.1021/jf0484632. ISSN 0021-8561.

- ^ Sumit Kumar; Ashu Bhan Tiku (2016). "Biochemical and Molecular Mechanisms of Radioprotective Effects of Naringenin, a Phytochemical from Citrus Fruits". J. Agric. Food Chem. 64 (8): 1676–1685. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b05067.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Chandra Jagetia, Ganesh; Koti Reddy, Tiyyagura; Venkatesha, V. A; Kedlaya, Rajendra (2004-09-01). "Influence of naringin on ferric iron induced oxidative damage in vitro". Clinica Chimica Acta. 347 (1–2): 189–197. doi:10.1016/j.cccn.2004.04.022.

- ^ Kanno, Syu-ichi; Tomizawa, Ayako; Hiura, Takako; Osanai, Yuu; Shouji, Ai; Ujibe, Mayuko; Ohtake, Takaharu; Kimura, Katsuhiko; Ishikawa, Masaaki (2005-01-01). "Inhibitory Effects of Naringenin on Tumor Growth in Human Cancer Cell Lines and Sarcoma S-180-Implanted Mice". Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 28 (3): 527–530. doi:10.1248/bpb.28.527.

- ^ So, Felicia V.; Guthrie, Najla; Chambers, Ann F.; Moussa, Madeleine; Carroll, Kenneth K. (1996-01-01). "Inhibition of human breast cancer cell proliferation and delay of mammary tumorigenesis by flavonoids and citrus juices". Nutrition and Cancer. 26 (2): 167–181. doi:10.1080/01635589609514473. ISSN 0163-5581. PMID 8875554.

- ^ van Meeuwen, J. A.; Korthagen, N.; de Jong, P. C.; Piersma, A. H.; van den Berg, M. (2007-06-15). "(Anti)estrogenic effects of phytochemicals on human primary mammary fibroblasts, MCF-7 cells and their co-culture". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 221 (3): 372–383. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2007.03.016.

- ^ Harmon, Anne W.; Patel, Yashomati M. (2004-05-01). "Naringenin Inhibits Glucose Uptake in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells: A Mechanism for Impaired Cellular Proliferation". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 85 (2): 103–110. doi:10.1023/B:BREA.0000025397.56192.e2. ISSN 0167-6806.

- ^ Hsu, Chin-Lin; Huang, Shih-Li; Yen, Gow-Chin (2006-06-01). "Inhibitory Effect of Phenolic Acids on the Proliferation of 3T3-L1 Preadipocytes in Relation to Their Antioxidant Activity". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 54 (12): 4191–4197. doi:10.1021/jf0609882. ISSN 0021-8561.

- ^ Mulvihill EE, Allister EM, Sutherland BG, Telford DE, Sawyez CG, Edwards JY, Markle JM, Hegele RA, Huff MW (October 2009). "Naringenin prevents dyslipidemia, apolipoprotein B overproduction, and hyperinsulinemia in LDL receptor-null mice with diet-induced insulin resistance". Diabetes. 58 (10): 2198–210. doi:10.2337/db09-0634. PMC 2750228. PMID 19592617.

- ^ Lee SH, Park YB, Bae KH, Bok SH, Kwon YK, Lee ES, Choi MS (1999). "Cholesterol-lowering activity of naringenin via inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase and acyl coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase in rats". Ann. Nutr. Metab. 43 (3): 173–80. doi:10.1159/000012783. PMID 10545673.

- ^ Yi LT, Liu BB, Li J, Luo L, Liu Q, Geng D, Tang Y, Xia Y, Wu D (October 2013). "BDNF signaling is necessary for the antidepressant-like effect of naringenin". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 48C: 135–141. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.10.002. PMID 24121063.

- ^ Gao, K; Henning, S; Niu, Y; Youssefian, A; Seeram, N; Xu, A; Heber, D (2006). "The citrus flavonoid naringenin stimulates DNA repair in prostate cancer cells". The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 17 (2): 89–95. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.05.009. PMID 16111881.

- ^ a b Katavic PL, Lamb K, Navarro H, Prisinzano TE (August 2007). "Flavonoids as opioid receptor ligands: identification and preliminary structure-activity relationships". J. Nat. Prod. 70 (8): 1278–82. doi:10.1021/np070194x. PMC 2265593. PMID 17685652.