Council of the Sephardi Committee

ועד העדה הספרדית בירושלים | |

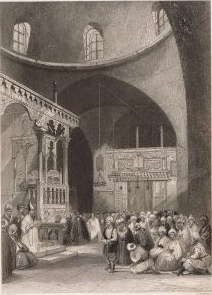

Istanbul Synagogue, property of the Council, 19th century | |

| Formation | 13th century |

|---|---|

| Founder | Nachmanides |

| Dissolved | 1980s (split) |

| Headquarters | Jerusalem |

Official language | Hebrew, Ladino |

President | Yehezkel Zakai |

The Council of the Sephardi Committee or Sephardi Community Council (Hebrew: ועד העדה הספרדית בירושלים) was a Jerusalem-based committee which served as an unofficial governing body for the Sephardi Jewish community in the city prior to Israeli independence. The organization purchased property from donations and endowments, which were then made available to Jews in need of shelter and resources.

History[edit]

According to tradition, the committee was established by Nachmanides, which served as a community binder for Jews for many years during Byzantine and Ottoman occupation of the Land of Israel. The organization was led by the Sephardic chief rabbi. Beginning in the 19th century, it was led by the Hakham Bashi, who was seen as the authority representative of the community in Israel towards the authorities of the Ottoman Empire, as well as the supreme authority in Jewish matters.[1][2]

During the mid-19th century, the committee suffered from fracturing due to ethnic differences, and the Western Community Committee split, followed by many other groups.[3]

By the beginning of the 19th century, the influence of the Sephardi Committee was greatly weakened due to the fact that most of the people who were making Aliyah were Ashkenazi, reducing the large majority the Sephardi community previously had.[2] Further fracturing in the community became evident after the death of Yaakov Shaul Elyashar in 1906, leading to a power struggle for the role of chief rabbi. Following WWI, the resources of the community had been greatly reduced.

British Mandate period[edit]

Two months after Mandatory Palestine was established, the committee was reorganized in a new format that lasted throughout the period as a legal entity. It had official duties, such as the supervision of the congregation's assets in Israel, its income, and the management of educational foundations in their holding.[4]

Following WWI, the president of the committee was lawyer Samuel Lupu. During WWII, the president of the committee was lawyer David Abulafia.[4]

The committee was diminished following the Holocaust, where many communities of Sephardi Jews in places like Thessaloniki, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia were killed or fled. Many Mizrahi Jews also immigrated to Israel following the exodus of Jews from the Middle East and North Africa.

State of Israel[edit]

After the establishment of Israel, a large part of the holdings ended up partitioned in the Palestinian territories under Transjordan. The committee also lost its rights over its endowment from Sima Balilius.

The power of the committee was further weakened by struggles within the Sephardic community during the leadership of Eliyahu Elyashar and David Seton.

In the mid-1980s, after the Association Law was passed, the committee was split into six sister associations, including the Spanish Community Committee, the Sephardic Kadisha Society,[5] and the Misgav Ladach Hospital.

Committee assets[edit]

The community committee owned a lot of real estate in Jerusalem. They owned a plot of land at the Mount of Olives for burial of their members, residential buildings for housing, and shops in Jerusalem. In the Old City, they included: Beit Gebul Almana, houses purchased for the poor,[6] Beit Tamhui, Talmud Torahs for poor children, and the courtyards around four Sephardic synagogues, one in the name of Yohanan ben Zakkai, and the Misgav Ladach. They also owned properties in the New City, such as houses by the Tora sanctuary in Mishkenot Sha'ananim, as well as many other houses in Yemin Moshe, Ibn Israel, Beit Israel, Mahane Yehuda, Zikhron Moshe, Rehavia, Shemaa, Kfar Shiloh, and Shimon HaTzadik. By the 1930s, about 530 people lived in apartments provided by the Council.

A large number of wealthy Jews entrusted large endowments to the community board, the largest of which was Sima Balilius of Calcutta's, who, in 1926, left 80,000 lira to the Yohanan ben Zakkai synagogue, along with dedicated funds for the purchase of four buildings for apartment complexes. Large endowments were also given by Haim Aharon Valero and Raphael Aharon Gabay, as well as from the Sephardic orphanage of the Borochoff and Wissachharoff families.

The Committee continued to manage the Misgav Ladach even after the establishment of the State of Israel[7] and built a new building for it in Katamon despite opposition from the Ministry of Health.[8] It operated as a private hospital without public support.[9] The building was initially built with donations from wealthy Sephardi benefactors, such as Nissim Gaon and Leon Taman.[10] The hospital went into debt and was sold to Kupat Holim Meuhedet; the liquidation of the hospital lasted many years and a lot of its endowment was sold to recuperate costs.[11][12]

External links[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Chaim, Avraham. "Archives of the Sephardic Community Committee in Jerusalem as a source for the history of the Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel under the Ottoman rule, Chair 1, Elul 2736" (PDF). ybz.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-04-05. Retrieved 11 Jul 2023.

- ^ a b Usuki, Akira (1993). "THE SEPHARDI COMMUNITY OF JERUSALEM BEFORE WORLD WAR I: A NOTE ON A DOMINANT COMMUNITY ON THE DECLINE". JSTAGE. Retrieved 11 Jul 2023.

- ^ שרעבי, רחל (1984). "התבדלות עדות-המזרח מהעדה הספרדית 1860—1914". Pe'amim: Studies in Oriental Jewry / פעמים: רבעון לחקר קהילות ישראל במזרח (21): 31–49. ISSN 0334-4088. JSTOR 23423330 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b Ḥayyim, Avraham (2000). Particularity and integration: the Sephardi leadership in Jerusalem under British rule (1917 - 1948). Yerûšalayim: Carmel. ISBN 978-965-407-233-5.

- ^ "ישראל היום | הקומבינות של יחזקאל זכאי". Israel Hayom. 2016-03-03. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2023-07-12.

- ^ בן אריה, יהושע (1977). עיר בראי תקופה - ירושלים במאה התשע-עשרה: העיר העתיקה (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: הוצאת יד בן צבי. p. 374.

- ^ "צו לתפיסת בי"ח "משגב לדך"". HaTzofe (in Hebrew). 4 Aug 1957. Retrieved 11 Jul 2023.

- ^ Horowitz, Shlomo (13 Aug 1986). "The new 'Mishgav Ladach' is established without the approval of the Ministry of Health". כותרת ראשית (in Hebrew). Retrieved 11 Jul 2023.

- ^ Arif, Ora (6 Jan 1984). "מבקשים _שזמחת !שנת [כתבה]". Maariv (in Hebrew). Retrieved 11 Jul 2023.

- ^ "נבון למסע־התרמה". כותרת ראשית (in Hebrew). 20 Jul 1983. Retrieved 11 Jul 2023.

- ^ בר-גיל, אורית (2006-08-27). "המחוזי: חיסול עמותת ביה"ח משגב לדך ייעשה בהתעלם מתביעות נזיקיות עתידיות". Globes (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2023-07-12.

- ^ צור, שלומית (2014-04-17). "שני בניינים היסטוריים בירושלים מוצעים למכירה". Globes (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2023-07-12.