Revista Illustrada

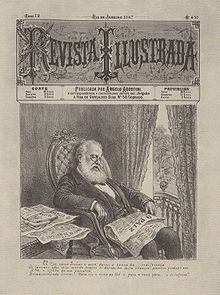

Cover of issue No. 450, 1887, depicting an old emperor Pedro II | |

| Categories | Satirical magazine Political magazine |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Weekly |

| Founder | Angelo Agostini |

| Founded | 1876 |

| Final issue | 1898 |

| Country | Brazil |

| Based in | Rio de Janeiro |

| Language | Portuguese |

Revista Illustrada was a Brazilian satirical, political, abolitionist and republican magazine. It was founded in Rio de Janeiro by Italian-born Brazilian illustrator Angelo Agostini, being issued from 1876 to 1898.

Features[edit]

With eight pages, the magazine had a weekly circulation of four thousand copies[1] portraying the events that occurred in a satirical way. It had no sponsors, nor did it run advertisements, and its only livelihood came from the sale of copies.[2] This was, however, only during the first phase of publication.[3]

The magazine had two distinct phases:

- The first, under the direction of Agostini, lasted until the Proclamation of the Republic in 1889, when Agostini - as well as emperor Pedro II - left the country; the latter, on account of the military coup; the former, for having run off with a mistress.[2][4]

- The second phase, under the direction of caricaturist Pereira Neto, worked intermittently. Agostini's return, in 1895, made Pereira just an employee. The magazine disappeared, definitively, shortly after.[2]

Researcher Marcus Tadeu Daniel Ribeiro, points out that the first phase of the magazine (from 1876 to 1888) was successful due to the fact that it reported the great aspirations of the public in an accessible language (to which the illustrations contributed), and for its complete independence and editorial freedom.[3]

Pioneering in comics[edit]

In 1884, Revista Illustrada published what is considered the first comic book in Brazil.[5] As Aventuras de Zé Caipora (The Adventures of Zé Caipora), aimed at children, brought to light the character that would come to be recurring in the magazine.[2]

Zé Caipora was features in covers of the magazine, such as number 369 and, when the 12-year commemorative edition of the magazine was published, a double sheet drawing was made on the central pages, a kind of poster, with the character.[1]

Opposition to the monarchy[edit]

Owner of an unmistakable trait, Agostini - who had already participated as an illustrator for other publications[2] - started his own weekly edition of the magazine, quickly becoming one of the great publications opposing the monarchic regime and slavery.

In its pages Agostini attacked the figure of emperor Pedro II in a persistent and acidic way, being considered one of those responsible for the deterioration of the monarch's public image. In an 1882 edition, the magazine brings a comic story where the emperor is accused of covering up the crown jewel thieves, as if he were their accomplice.[4] Such attacks exerted great influence on contemporary public opinion.[2]

Its anti-slavery stance was so polished that one of the main leaders of abolitionism, Joaquim Nabuco, nicknamed it the "Bible of Abolition". At the time of the Golden Law, the magazine dedicated an issue whose cover became famous with the figuration of the party for the end of slavery.[2]

Famous dispute[edit]

The Revista Illustrada competed with the magazine O Besouro, under the direction of Portuguese artist Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro (1846-1905). According to Portuguese researcher José Augusto França, Agostini's provocations in the Revista Illustrada led Bordalo to react in a violent and explosive way. The episode of provocation took place between November and December 1878, when Agostini provoked his rival, driven by the fall of buyers among the large Portuguese community in Rio de Janeiro. When Bordalo reacted, he portrayed Agostini as a shoeshine boy, sending him "on the sidelines". Agostini reacted, saying that "We appreciate the finesse. We know how to recognize that the edge of O Besouro is the cleanest place on this page". Bordalo's collaborators left the magazine, which closed, with Bordalo returning to Portugal in March of the following year.[3]

The Republic and the end[edit]

With the advent of the republic in Brazil and the end of slavery, the country did not undergo major changes; The original critical content lost its meaning and Agostini no longer was the spokesperson for popular desires, grappling with the new regime. The Revista Illustrada went silent during the dictatorial government of Floriano Peixoto, and living its second phase in dependence and involvement with the republican government, it lost its complicity with the public, disappearing definitively.[3]

Gallery[edit]

-

Zé Caipora comic

-

Cover of issue No. 429, 1886, depicting Quintino Bocaiúva painting a picture alluding to yellow fever, while the public authorities, represented as cows, watch the scene impassively.

-

Cover depicting José Bonifácio with the caption: Independence festivities. Big trouble in Largo de São Francisco on the night of September 8. Patriarch Bonifácio, losing his patience, was almost ready to react against the troublemakers.

-

Cover of issue No. 376, 1884, depicting Francisco Nascimento with the caption: At the head of the Ceará raftsmen, Nascimento prevents the traffic of slaves from the province of Ceará to be sold on the south.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Cavalcanti, Carlos Manoel de Hollanda (2006). "Angelo Agostini e seu "Zé Caipora" entre a Corte e a República"" (PDF). História, imagem e narrativas (3). ISSN 1808-9895. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Histórico da Revista Illustrada". Almanaque. Archived from the original on 10 January 2008.

- ^ a b c d Ribeiro, Marcus Tadeu Daniel (2006). "A Arte de Alfinetar". Nossa História. No. 30. pp. 70–73.

- ^ a b Aragão, Octavio (2005). "O Império da Sátira". Revista Nossa História. No. 26. Vera Cruz. pp. 32–34.

- ^ "Angelo Agostini". Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010.