Philae obelisk

The Philae obelisk is one of a pair of twin obelisks erected at Philae in Upper Egypt in the second century BC. It was discovered by William John Bankes in 1815, who had it brought to Kingston Lacy in Dorset, England, where it still stands today. The Greek and Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions on the obelisk played a role in the decipherment of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Description[edit]

The obelisk was originally one of a pair that stood at the east pylon of the temple of Isis at Philae.[1] The other obelisk of the pair was broken into pieces in antiquity. The surviving obelisk consists of a long shaft, topped by a pyramidion and a rectangular base. The bottom of the shaft is a modern restoration. Including the modern base, it stands roughly seven metres tall.[2] There are two inscriptions: a hieroglyphic text on the shaft and a Greek text on the base. The first half of the Greek text was only painted in red colour and is not longer visible, the second half was inscribed.[3] The inscriptions are published in the Corpus of Ptolemaic Inscriptions as number 424.[4] The text on the shaft can be dated to 131–124 BC;[5] the greek inscription on the base is slightly younger and is dated to the years 124–117 BC.[6]

The inscriptions on the base record a petition by the Egyptian priests at Philae and the favourable response by Ptolemy VIII Euergetes and queens Cleopatra II and Cleopatra III, who reigned together from 144-132 BC and again from 126-116 BC. The priests complained about the financial burden resulting from the large numbers of royal functionaries visiting their sanctuary. The king and queens approved the request and instructed the governor to stop having the temple service the state officials.[7]

Acquisition[edit]

Bankes noticed the obelisk in 1815, while travelling in Egypt and believed that the bilingual inscription would help with the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs. He accordingly acquired the obelisk and a single, large broken piece of its twin found at Philae and had them transported to his estate at Kingston Lacy in Dorset, England. The operation was carried out by the adventurer Giovanni Belzoni.[8] The obelisk arrived in London in December 1821, making it the first Egyptian obelisk to be brought to the United Kingdom.[9]

Arthur Wellesley provided a gun carriage which transported the obelisk to Kingston Lacy in Dorset in 1829 and George IV provided Libyan granite which was used to repair the base of the obelisk's shaft. The obelisk was set up as a central feature of the gardens in 1830; nineteen horses were required to raise it into position.[9] The broken piece of the twin was set into the lawn nearby as a romantic ruin.

The obelisk was bequeathed to the National Trust along with the house and estate in 1981.[10] The obelisk is a Grade II* listed building.[11]

Decipherment of hieroglyphs[edit]

Discussing the obelisk's role in the decipherment of hieroglyphs, C.W. Ceram characterised the obelisk as "in effect a second Rosetta Stone."[12] Several lithographs of the obelisk and its inscriptions were produced by George Scharf while it was in London.[9] Bankes distributed these lithographs to various contemporaries interested in deciphering hieroglyphs. In his studies of the Rosetta Stone, the scholar Thomas Young had already realised that the cartouches contained the names of the Pharaohs and he had identified the name 'Ptolemy'. In a marginal note on some of the lithographs, Bankes proposed to identify the name 'Cleopatra' in cartouches on this inscription. However, further progress was stymied by the fact that the Greek and Egyptian texts were not close parallels of one another and by Bankes and Young's incorrect belief that Egyptian hieroglyphs were logographic.[13]

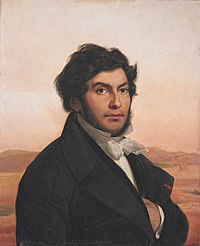

In France, Jean-François Champollion was also working on the decipherment of hieroglyphs. Based on his earlier work on demotic, he had constructed a hypothetical hieroglyphic text for the name 'Cleopatra'. Jean-Antoine Letronne sent him a copy of the lithograph of the Philae obelisk, which confirmed that his reconstruction was correct and he announced the decipherment of hieroglyphs in the Lettre à M. Dacier in 1822.[14] Bankes, Young, and their circle responded to this announcement with great hostility, claiming that Champollion had not given them proper credit for the discovery.[15][16] The obelisk was subsequently investigated by Karl Richard Lepsius, who published its text in 1839. Further autopsy was carried out by Ulrich Wilcken in 1887, who reported that the painted Greek inscription was no longer visible by this time. Subsequent publications on the obelisk and its text have all been based on the reports of these nineteenth century observers.[17]

Digital research[edit]

By 2014, the inscriptions had been heavily weathered. The Greek inscription, in particular, was barely visible to the naked eye. In October and November 2014 and spring 2015, Ben Altshuler of the Institute for Digital Archaeology, in association with Alan Bowman and Charles Crowther of Oxford's Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents (CSAD), undertook RTI scans and 3D imaging of the obelisk, in conjunction with a commercial measurement company called GOM UK.[18][19][20] The resulting scans demonstrated that Scharf's lithograph was an accurate representation of the hieroglyphic text and enabled "some small corrections" to the recorded version of the Greek text. Some possible traces of the painted Greek text were also detected.[21]

The obelisk, in keeping with its bilingual nature and the "translation" metaphor of the Rosetta space mission, gives its name to the mission Philae robotic lander,[22] which arrived at the comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko on 6 August 2014[23] and landed on 12 November 2014.[24][25]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Masséglia 2020, p. 11.

- ^ Masséglia 2020, p. 10.

- ^ Pfeiffer 2015, p. 150.

- ^ Bowman, Alan; Crowther, Charles; Hornblower, Simon; Mairs, Rachel; Savvopoulos, Kyriakos (2021). Corpus of Ptolemaic Inscriptions: Volume III: Southern Border, Oases, and Incerta. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198860495.

- ^ Minas, Martina (2000). Die hieroglyphischen Ahnenreihen der ptolemäischen Könige. Ein Vergleich mit den Titeln der eponymen Priester in den griechischen und demotischen Papyri. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Pfeiffer 2015, p. 152-153.

- ^ Pfeiffer 2015, p. 149-154.

- ^ Belzoni's account is published in Siliotti, A. (2001). Belzoni's Travels: Narrative of the Operations And Recent Discoveries in Egypt and Nubia. London: British Museum Press.

- ^ a b c Masséglia 2020, pp. 11–12.

- ^ "Kingston Lacy - History". National Trust. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ Historic England. "Obelisk 140m south west of Kingston Lacy House (1323828)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ Ceram, C.W. (1967). Gods, Graves & Scholars. New York: Wings Books. p. 109. ISBN 9780517119815.

- ^ Masséglia 2020, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Masséglia 2020, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Masséglia 2020, p. 14.

- ^ Usick 2002, pp. 77–80.

- ^ Masséglia 2020, pp. 15 & 19.

- ^ Masséglia 2020, pp. 14–15.

- ^ "Philae Lander, Like Philae Obelisk, Is a Window to the Past". Space.com. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ "Imaging". The Institute for Digital Archaeology. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ Masséglia 2020, p. 16-17.

- ^ Morris, Steven (23 October 2014). "Rosetta mission: Philae comet probe could unlock secrets of the universe". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ "Europe's Rosetta probe goes into orbit around distant comet". BBC News. 6 August 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ "Europe makes history with first ever comet landing". Government of the United Kingdom. 12 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ Masséglia 2020, p. 19.

Bibliography[edit]

- Edwyn R. Bevan, The House of Ptolemy (London: Methuen, 1927) pp. 322–23 Textus

- E. A. Wallis Budge, The decrees of Memphis and Canopus (3 vols. London: Kegan Paul, 1904) vol. 1 pp. 139–59

- Erik Iversen, Obelisks in exile. Vol. 2: The obelisks of Istanbul and England (Copenhagen: Gad, 1972) pp. 62–85

- T. G. H. James, Egyptian antiquities at Kingston Lacy, Dorset: the collection of William John Bankes. San Francisco: KMT Communications, 1993–94

- Masséglia, Jane (2020). "Imaging Inscriptions: The Kingston Lacy Obelisk". The Epigraphy of Ptolemaic Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 9–19. ISBN 9780198858225.

- Pfeiffer, Stefan (2015). Griechische und lateinische Inschriften zum Ptolemäerreich und zur römischen Provinz Aegyptus. Einführungen und Quellentexte zur Ägyptologie (in German). Vol. 9. Münster: Lit. pp. 149–154.

- Anne Sebba, The exiled collector: William Bankes and the making of an English country house. London: John Murray, 2004

- Usick, Patricia (2002). Adventures in Egypt and Nubia : the travels of William John Bankes (1786-1855). London: British Museum Press. ISBN 9780714118031.