Murder of Billy Jack Gaither

| Murder of Billy Jack Gaither | |

|---|---|

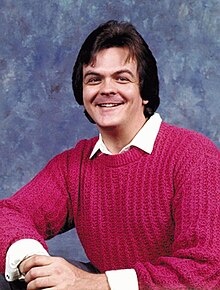

Family photo of Gaither | |

| Location | Sylacauga, Alabama, U.S. |

| Date | February 19, 1999 |

Attack type | Gay bashing |

| Victims | Billy Jack Gaither, 39 |

| Perpetrators | Steven Eric Mullins Charles Monroe Butler |

| Motive | Homophobia |

| Convicted | Capital murder |

The murder of Billy Jack Gaither took place in Alabama on February 19, 1999. Two acquaintances, Steven Eric Mullins and Charles Monroe Butler, beat Gaither to death, slashed his throat, and burned his body. Both admitted that they murdered Gaither because of his sexual orientation, as Gaither, who was 39 at the time of his murder, was a gay man.

Mullins, who took a plea deal to avoid the death penalty, argued that both he and Butler were equally responsible for Gaither's murder, while Butler argued at trial that Mullins was the primary aggressor in the crime. Butler was convicted of murder as well, and both men received sentences of life without parole.

Gaither's murder gained significant coverage in state and national news, especially as it occurred in relatively close proximity to the similar high-profile murders of Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr, both of which were motivated by prejudice against sexual and racial minorities respectively. In 2000, Gaither's murder was covered in a PBS Frontline special called "Assault on Gay America: The Life and Death of Billy Jack Gaither." The murder sparked calls to change Alabama's hate crimes law, which, at the time of its passage in 1994, did not cover crimes based on sexual orientation or gender identity.[1]

Background[edit]

Billy Jack Gaither[edit]

Gaither was religious and came from a Christian family; he sang in a choir at his Baptist church.[2] One of Gaither's friends asserted that Gaither largely remained closeted to his parents due to their religious convictions. Gaither's brother said he knew Gaither was gay from an early age and that "you did not want to agree with it, but [Billy] was his own person."[3] Gaither's father allegedly struggled to accept the notion of Gaither's homosexuality and told reporters after Gaither's murder that Gaither almost married a woman while he lived in Birmingham, Alabama, although he and Gaither's mother insisted that Gaither was protective and that Gaither had cared for his father after his father underwent thirteen operations.[2][4] Gaither had two sisters, one of whom, Kathy, was a lesbian.[5]

Gaither had dropped out of Sylacauga High School when he reached the 11th grade and obtained his GED, after which he joined the Marines and served for a year. He was honorably discharged due to his hypertension. Upon moving back to Sylacauga, Gaither frequented gay bars in Birmingham and Montgomery, Alabama, and had brief relationships with at least two men.[2] Gaither was also a regular at a non-gay bar called The Tavern, where the owner of the bar, Marion Hammond, stated Gaither would help her decorate the bar for holidays. She stated that Gaither "was not ashamed of who he was" and that "[h]e would not flaunt his gayness, but if someone asked if he was a 'fag' or 'queer', he would say yes." Gaither's brother also stated that Gaither attended gay bars in Atlanta.[3][6]

At the time of his death, Gaither worked as a computer terminal operator at a Russell Athletic location in Alexander City, Alabama, a small town near Sylacauga.[2][7] He also served as a caretaker for his disabled parents, with whom he lived in Sylacauga. Gaither frequented flea markets and collected memorabilia and trinkets related to Gone with the Wind, including posters and Scarlett O'Hara dolls.[2][8] Locals described Gaither as gentle and quiet.[9]

Perpetrators[edit]

Prior to the murder, Steven Eric Mullins identified as a skinhead. Sylacauga locals claimed Mullins often wore Ku Klux Klan shirts, sported Confederate flags, and made racist comments and taunts against black people, although he was not known prior to be a threat to the LGBT population.[2] Mullins was also a regular at The Tavern.[8] On one occasion, while wearing a KKK shirt, Mullins noticed black people in a restaurant and pressed his back against the window so they would be forced to see the racist symbols and messages on his shirt. On another occasion, while at The Tavern, Mullins mocked black patrons with racial epithets.[8]

Mullins had spent time in prison prior to Gaither's murder after convictions of burglary and forgery. He did not have a close relationship with his father, who he claimed he only saw a few times, the second time being when the two were coincidentally serving jail sentences at the same time for different charges.[9]

During his trial, witnesses testified that Mullins had experience with same-sex acts.[7] Mullins denied having sexual experiences with men and insisted he was heterosexual.[9][10] Mullins alternated between working in construction and being unemployed.[8]

Charles Monroe Butler also worked in construction in Sylacauga. Butler's stepmother attested she had never heard Butler express homophobic sentiments, stating, "It wasn't a big issue here, but it might have been when he was out with his friends."[8]

At the time of the murder, Mullins was 25, and Butler was 21.[5] Mullins and Butler were familiar with each other dating back several years because Mullins lived with two of Butler's half-brothers, but the younger Butler had acted as Mullins' "sidekick" for only a month by the time Gaither was murdered.[8]

Local attitudes toward the LGBT community[edit]

Local LGBT residents of Sylacauga stated that it was uncommon at the time for anyone to be openly gay in the town and that, while violent incidents like Gaither's murder were rare, there was not a lot of local acceptance of LGBT people.[2] David W. White, the Birmingham coordinator for the Gay and Lesbian Alliance of Alabama, said after the murder that he "would consider it difficult to live anywhere in Alabama other than Birmingham" and that "[e]ven in Birmingham, I would never in a public place grab my partner's hand and walk down the street. It would literally be a death wish in the state of Alabama."[5]

One of Gaither's friends recalled an occasion prior to the murder when a group of businesses in downtown Sylacauga decided to hang a series of flags to "spruce up" the area. One of the flags contained a "rainbow symbol [that] was sometimes used by gay groups," prompting a local church to campaign for the flag's removal because its presence "promoted a gay lifestyle in Sylacauga." The flag was ultimately taken down.[8]

Murder[edit]

Steven Mullins claimed in his confession to Sylacauga authorities that Gaither had sexually propositioned him over the phone two weeks prior to the murder and that he felt Gaither's overture "broke the respect line" Mullins thought the two had established. Gaither's friends disputed that he would have propositioned anyone, insisting that Gaither was too careful to make such a solicitation. Nevertheless, Mullins claimed the alleged proposition led him to murder Gaither, stating, "I didn't feel like he needed to live any longer."[9]

Mullins told authorities that he and Gaither spoke on the phone multiple times after Mullins resolved to murder him and that Gaither agreed to pick up Mullins from the trailer where Mullins was staying, so the two could visit a bar.[11][12][13] The two went bar-hopping for several hours before ending up at a bar where Charles Butler was inside playing pool.[12] Gaither stayed in the car, while Mullins entered the bar. Mullins claimed he told Butler about his plans to murder Gaither because Mullins "thought [he] could trust [Butler]" and "knew [Butler] didn't like queers either."[13] After Butler finished his game of pool, he and Mullins convinced Gaither to join them at a slipway off of a rural highway.[13]

The three then drove to the slipway in Gaither's car, where Butler got out of the car to urinate by the front of the car. Mullins confessed to Sylacauga investigators that while Butler was urinating, Mullins and Gaither were standing behind the car when Mullins grabbed Gaither, threw him onto the ground, and slit his throat with a pocketknife. The injury to Gaither's throat was not lethal, but it was profusely bleeding.[12] Mullins instructed Butler to open the trunk of their car, at which point Gaither attempted to escape. Mullins stabbed Gaither twice more "in the rib cage" and then demanded that Gaither enter the trunk of the car. After Gaither climbed into the trunk, Mullins and Butler shut the trunk door and drove away from the slipway to retrieve two tires, a gallon of kerosene, a matchbox, and an axe handle from the trailer where Mullins was staying with Butler's half-brothers.[11][12]

Mullins and Butler then drove Gaither to a creek. Mullins claimed that as he pulled Gaither out of the trunk, Butler doused the tires with kerosene and lit them on fire. Gaither attempted to escape one final time, knocking Mullins into the creek and trying to leave in his car, but Gaither did not have the keys to the car. Mullins dragged Gaither away from the car and beat him with the axe handle, while Butler wiped Gaither's blood out of the car with a shirt. When Mullins tired of beating Gaither, he stated that he dragged Gaither to the fire and that he and Butler "stood there for a few minutes" watching Gaither burn before they left the scene.[14] Both Mullins and Butler agreed that Gaither was dead by the time he was dragged to the burning tires, although at trial, Butler claimed he ran away before Mullins delivered the fatal blows with the axe handle, and that he returned to help with burning Gaither's body and later burning Gaither's car to eliminate evidence.[11] The next day, Gaither's body was found on a riverbank near a local church known for hosting baptisms.[2][14]

Reaction[edit]

Politicians[edit]

U.S. President Bill Clinton and First Lady Hillary Clinton offered the Gaither family their condolences after the murder, releasing a statement calling the crime "heinous and cowardly" and comparing it to the recent hate murders of James Byrd Jr. in Texas and Matthew Shepard in Wyoming.[3] Clinton's statement also read, "In times like these, the American people pull together and speak with one voice, because the acts of hatred that led to the deaths of such innocent men are also acts of defiance against the values our society holds dear."[8]

On May 11, 1999, United States Deputy Attorney General Eric Holder released a statement condemning Gaither's, Byrd's, and Shepard's murders as well, branding all three hate crimes and quoting an Alabama newspaper that said Gaither was murdered "for being himself." Holder's statement asserted the American government's commitment to "prosecuting and preventing" hate crimes and called for the federal government to take a stronger stand against hate crimes.[15]

California governor Gray Davis stated to a crowd in West Hollywood, California, that Gaither's murder "deeply grieved" him "because it strikes at the very heart of what it means to be an American." He also stated, "If any man or woman cannot walk safely down our streets for fear of violence simply because of his or her sexual orientation, then none of us are truly free."[5]

Organizations[edit]

Weeks after Gaither's murder, LGBT rights activists attended an event in Birmingham's Covenant Metropolitan Community Church to advocate for Alabama's hate crime laws to include protections for sexual orientation. During the event, members of the Westboro Baptist Church stood across the street holding signs criticizing Gaither. Their leader, Reverend Fred Phelps, criticized the LGBT community for "exploiting" Gaither's murder and said, "It is no longer merely an event for the family and friends to grieve."[5]

Gaither's family[edit]

Some members of Gaither's extended family, including Gaither's uncle, expressed that they thought homosexuality was morally wrong but that Gaither did not deserve to be murdered for it. Gaither's uncle also lamented that the murder would "get all these gay activists involved."[3]

Gaither's family members were split in their support of the death penalty for Mullins and Butler, with some, including Gaither's brother, expressing that he wished to see the killers executed because "They took my brother's life. Why can't the state take their lives?"[16] Gaither's father opposed the death penalty, as he could not "see taking another human being's life, no matter what."[5]

Investigation and arrests[edit]

Investigators found Gaither's blood, hair, and teeth around the crime scene.[12] Gaither's official cause of death was determined to be blunt force trauma caused by the beating with the axe handle. Gaither's face and jaw had sustained severe injuries, and he had more than a dozen skull fractures.[9]

Investigators asked Alabama's LGBT community to stay quiet about Gaither's murder until their investigation was finished to prevent from interfering with investigators' work. Figureheads in the community complied; David White, the state coordinator of Equality Alabama, stated that they complied because they "wanted to make certain [Gaither's murder] was not one of those things that would be swept under the rug."[17]

Butler told his father about his involvement in the murder. His father told coworkers, who alerted law enforcement.[9] Butler was arrested on March 1, 1999, two days before Mullins.[4] Butler alleged that he confessed because he was having trouble sleeping after the murder.[18] In Butler's confession, he claimed that Mullins mentioned wanting a threesome with Gaither and Butler, and Butler responded by kicking and punching Gaither; he claimed Mullins beat Gaither to death single-handedly because of either Gaither's alleged refusal to "pay," or Gaither's alleged insistence he would reveal Mullins' gay activities.[19] Two days later, while in jail on a charge unrelated to Gaither's murder, Mullins admitted his involvement in Gaither's murder, although his statement implicated Butler as a far more willing accomplice than Butler's own statement implied.[18] Coosa County, Alabama, Sheriff Deputy Al Bradley claimed Mullins said he needed to confess because "God told him he needed to confess."[17]

After their arrests, Mullins and Butler were detained in the Coosa County Jail, with bond set at $500,000 for each. Their case was given to a grand jury on March 17.[2] On March 29, a preliminary hearing for Mullins and Butler took place; authorities ordered a change of venue from Coosa County to Elmore County, Alabama, because they believed Coosa County's facilities would be unable to accommodate the massive amounts of reporters and other media representatives.[20]

Trial[edit]

Mullins and Butler were charged with capital murder, a death penalty-eligible offense, because of Gaither's kidnapping being an aggravating factor.[21] In late May 1999, Mullins and Butler pleaded not guilty to Gaither's murder. The trial was scheduled to take place on August 2. Butler also pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, although his attorney indicated Butler would not attempt to make an insanity defense at trial and was only making the plea to "[cover] all the bases."[16]

In June 1999, Mullins pleaded guilty to Gaither's murder.[22] While Butler was expected to do the same, on August 2, 1999, he rejected the plea offer and decided to go to a full jury trial. The plea offer would have given Butler a default sentence of life without parole, but rejecting the offer made him eligible for the death penalty.[22]

Butler's trial began on August 3 in front of a jury of six men and six women.[22] Prosecutors argued at Butler's trial that he was a willing participant in the murder of Gaither and the concealment of the body. Butler's attorney argued to the jury on his behalf that Butler was ignorant to Mullins' plans and that Mullins, who was larger, stronger, and older, forced Butler to help him.[22]

Butler's defense attorney argued that the only evidence implicating Butler in capital, premeditated murder was Mullins's confession and that proof of Butler's lack of premeditation was the fact that Butler did not have a weapon with him.[12] Butler's attorney also claimed that Gaither's murder was motivated by Mullins's desire to get money from Gaither, and not prejudice against LGBT people.[10] To make that case, Butler's attorney called Mullins to the stand and asked about a purported boyfriend from Mullins's past, but Mullins denied having a boyfriend. Mullins did testify that money was part of his motivation for murdering Gaither, that he had known Gaither for eighteen months prior to the crime, and that he lived in a trailer with an openly gay man at the time he was arrested, but he attested that he also murdered Gaither because Gaither was gay.[10] Butler's attorney called several members of Alabama's gay community to the stand, one of whom testified that he had engaged in oral sex with Mullins, a claim Mullins steadfastly denied.[19]

Butler testified at his trial to his version of events, wherein Mullins was the primary aggressor and Butler was an unwilling accomplice. Butler cried on the stand as he claimed he only participated in the crime due to his fear of Mullins.[19] During cross-examination, prosecutors asked why he did not tell his half-brothers, with whom Mullins lived, about what he and Mullins had done to Gaither, and Butler was unable to answer. Butler also refused to look at photos of Gaither's burned body when prosecutors held up the photos for him.[23]

During closing statements, prosecutors held up color photos of Gaither's burnt body for the jury to see and called Mullins and Butler "two pieces of pure evil."[19]

Conviction and sentencing[edit]

The jury took two and a half hours to deliberate Butler's case. During their deliberations, prosecutors removed the death penalty as a sentencing option due to a request from Gaither's family.[19] The jury returned a guilty verdict on the afternoon of August 5, and moments afterwards, Butler was sentenced to life without parole. Gaither's father expressed pleasure with the sentence. The next day, August 6, Mullins was formally sentenced to life without parole as well.[19][24]

Immediately upon Butler receiving his sentence, one of Butler's attorneys expressed a desire to file for a mistrial due to alleged prosecutorial misconduct, due to the prosecution's neglect to inform the defense that Mullins was ineligible for the death penalty due to his cooperation.[23]

On April 28, 2000, Butler's life sentence was upheld by the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals, with a majority opinion rejecting Butler's request for a new trial. Butler's appeal had argued that Mullins was almost entirely responsible for Gaither's murder, while the appeals court argued that the severity of Butler's sentence was appropriate based on the evidence presented at trial of Butler's own involvement and motivations for wanting to murder Gaither. Butler's appeal also challenged the fact that the jury was never given the choice to convict Butler of manslaughter, while the appeals court found no basis for Butler's argument.[25]

Aftermath[edit]

The same year as Gaither's murder, members of the LGBT community in Alabama began holding an annual candlelight vigil on the steps of the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery, commemorating Gaither and other victims of homophobic hate crimes. The vigil was originally organized by Equality Alabama, a nonprofit civil rights organization advocating for the rights of Alabama's LGBT population. At the vigil, members of the community present the Billy Jack Gaither Humanitarian Award.[14]

In 1996, PBS sponsored a documentary film called It's Elementary: Talking About Gay Issues in School, intended to promote tolerance of LGBT people amongst schoolchildren. The documentary received little support at the time of its release and was the target of backlash from anti-gay organizations like the American Family Association, but in 1999, it gained popularity. Its director, Debra Chasnoff, attributed the popularity of the film to a rise in homophobic violence and language, stating, "Sadly, part of the reason I think the film is being picked up [now] is because of the time. Our campaign falls within the same window of time that the Matthew Shepard murder and trial are going on, the murder of Billy Jack Gaither, and now Colorado," referring to the homophobic language that had been used to harass the perpetrators of the 1999 Columbine High School massacre.[26]

Gaither's murder helped to spur attempts by state lawmakers to change Alabama's hate crime law so it would protect sexual orientation and gender identity. At the time of the murder, Alabama was one of 19 states whose hate crime laws did not cover crimes motivated by LGBT identity. Alabama State Representative Alvin Holmes was motivated by both Gaither's and Matthew Shepard's murders to file a bill extending hate crime laws in Alabama to protect the LGBT community.[18] As of 2019[update], the law had not changed.[14][27]

Imprisonment of Mullins and Butler[edit]

Mullins claimed during his time in prison that he had since disavowed the Neo-Nazism he had embraced prior to murdering Gaither and that, while he once believed people "other than the white race [were] just evil [and] didn't belong on the Earth," he thought of himself as a different person from the one who murdered Gaither: "I've often felt that [the man who killed Gaither] was like another person. You know, somebody else inside me."[9]

On February 26, 2019, officials at the St. Clair Correctional Facility in Springville, Alabama, found Mullins unresponsive in a housing area. He was airlifted to a hospital and later pronounced dead of multiple stab wounds. He was 45 years old. The Alabama Department of Corrections announced that they would file capital murder charges against the inmate suspected of stabbing Mullins, Christopher Scott Jones.[14] Mullins's death was the fourth murder to occur at St. Clair Correctional Facility in a six-month span, prompting the Equal Justice Initiative to argue that authorities did not provide adequate protection to at-risk inmates at the facility; the EJI alleged that authorities had denied Mullins protection from threats of sexual assault and murder in the weeks prior to his death, even when he had reported the threats and requested assistance.[28]

As of March 2019[update], Butler was incarcerated at the William E. Donaldson Correctional Facility near Bessemer, Alabama.[14]

See also[edit]

- History of violence against LGBT people in the United States

- List of acts of violence against LGBT people

- Matthew Shepard

- Murder of James Byrd Jr.

References[edit]

- ^ "Billy Jack Gaither". University of Alabama: University Libraries | Empowering Voices. Archived from the original on 2023-05-31. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Firestone, David (1999-03-06). "Murder Reveals Double Life Of Being Gay in Rural South". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2023-01-30. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

- ^ a b c d "Gaither (Continued from Cover)". Seattle Gay News. 1999-03-12. p. 21. Archived from the original on 2023-08-09. Retrieved 2023-08-09 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Suspects Say They Killed Man for Being Gay". San Francisco Examiner. 1999-03-04. p. 16. Archived from the original on 2023-08-23. Retrieved 2023-08-23 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Gray, Jeremy (2019-02-19). "Billy Jack Gaither was savagely murdered in 1999 because he was gay in Alabama". AL.com. Archived from the original on 2023-05-31. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ "Friends and Family Remember Billy Jack Gaither: Alabama Friends Shocked at Gruesome Murder". Seattle Gay News. 1999-03-12. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2023-08-09. Retrieved 2023-08-09 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "The Life and Death of Billy Jack Gaither | Assault on Gay America | FRONTLINE | PBS". PBS. 2000. Archived from the original on 2023-05-31. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Suspect Known for Taunting Blacks in Town". The Akron Beacon Journal. 1999-03-06. pp. A10. Archived from the original on 2023-08-09. Retrieved 2023-08-09 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g Garland, James Allon (2000). "The Low Road to Violence: Governmental Discrimination as a Catalyst for Pandemic Hate Crime". Tulane Journal of Law and Sexuality. 1: 1–91. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-08-24.

- ^ a b c "Defense Plans Big Day with Witnesses (Continued from Page 1)". Birmingham Post-Herald. 1999-08-05. p. 7. Archived from the original on 2023-08-23. Retrieved 2023-08-23 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Defense: Butler Not Accomplice". Birmingham Post-Herald. 1999-08-04. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2023-08-23. Retrieved 2023-08-23 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f "Defense: Butler Not Accomplice (Continued from Page 1)". Birmingham Post-Herald. p. 8. Archived from the original on 2023-08-23. Retrieved 2023-08-23 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Statement of Steven Eric Mullins re: Homicide of Billy Jack Gaither". PBS Frontline. 1999-03-03. Archived from the original on 2023-08-23. Retrieved 2023-08-23.

- ^ a b c d e f Bonvillian, Crystal (2019-03-04). "Killer in infamous 1999 murder of gay Alabama man stabbed to death in prison". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. ISSN 1539-7459. Archived from the original on 2023-05-31. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

- ^ "Statement of Eric H. Holder, Jr., Deputy Attorney General, Before the Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate Concerning Hate Crimes". United States Department of Justice. 1999-05-11. Archived from the original on 2023-08-23. Retrieved 2023-08-23.

- ^ a b "Two Plead Innocent in Slaying". Montgomery Advertiser. 1999-05-21. pp. 3B. Archived from the original on 2023-08-22. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ a b "Two Charged in Gay Man's Death". York Daily Record. 1999-03-05. p. 4. Archived from the original on 2023-08-23. Retrieved 2023-08-23 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Gay Man's Murder Haunts a Town". CBS News. 1999-03-05. Archived from the original on 2023-08-23. Retrieved 2023-08-23.

- ^ a b c d e f Joynt, Steve (1999-08-06). "Verdict Disappoints Butler's Lawyer". Birmingham Post-Herald. pp. E1. Archived from the original on 2023-08-23. Retrieved 2023-08-23 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Slaying Thrusts Rural Alabama County into Spotlight". Seattle Gay News. 1999-03-19. pp. A2. Archived from the original on 2023-08-09. Retrieved 2023-08-09 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "BUTLER v. STATE (2000)". FindLaw. 2000-04-28. Archived from the original on 2023-08-23. Retrieved 2023-08-23.

- ^ a b c d "Grisly Details Mark the Start of Trial in Slaying of Gay Man". Tampa Bay Times. 1999-08-04. Archived from the original on 2023-08-09. Retrieved 2023-08-09.

- ^ a b "Verdict Disappoints Butler's Lawyer (Continued from Page E1)". Birmingham Post-Herald. 1999-08-06. pp. E2. Archived from the original on 2023-08-23. Retrieved 2023-08-23 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Man Draws Life Sentence in Slaying of Homosexual". Montgomery Advertiser. 1999-08-06. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2023-08-23. Retrieved 2023-08-23 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Leonard, Arthur S, ed. (June 2000). "Lesbian/Gay Law Notes". Queer Resource Directory. ISSN 8755-9021. Archived from the original on 2023-08-23. Retrieved 2023-08-23.

- ^ Schenden, Laurie (1999-06-08). School's 'Out' for Summer. Here Media. p. 64. Archived from the original on 2022-01-06.

- ^ Day, Samantha (2019-02-17). "Crimes against Alabama's LGBTQ community not considered hate crimes". WSFA. Archived from the original on 2023-05-31. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

- ^ Gray, Jeremy (2019-03-07). "Report: Inmate stabbed to death at St. Clair prison was denied protection". Anniston Star. Archived from the original on 2023-05-31. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- 1999 in Alabama

- 1999 in LGBT history

- 1999 murders in the United States

- American victims of anti-LGBT hate crimes

- Deaths by person in Alabama

- February 1999 crimes in the United States

- Hate crime in the United States

- Homophobia

- Incidents of violence against men

- LGBT history in Alabama

- Violence against gay men in the United States