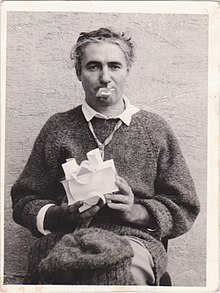

Mihai Olos

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Mihai Olos | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 26 February 1940 Ariniș, Maramureș County, Romania |

| Died | 22 February 2015 (aged 74) Amoltern, Germany |

| Nationality | Romanian |

| Notable work | Matraguna, OlosPolis, Orașul Universal |

| Website | olos |

Mihai Olos (born 26 February 1940 in Ariniș, Romania – died 22 February 2015 in Amoltern, Endigen, Germany) was a Romanian conceptual artist, poet, essayist.

A gifted colorist in his first paintings, he became more attracted towards experimenting with various forms and materials. Familiar with the rural wood culture, he intended to follow in the footsteps of Constantin Brâncuși, combining the spirit of the local folk culture with the trends of modern and contemporary art. Intending to take further the great sculptor's experience, Olos transformed the spindle-head – a miniature of the nail-less junctions in the architecture of the wooden churches of Maramureș – into a constructive module for the project of a universal city he called "Olospolis" that he theorized and represented in different forms and materials. While living and working in Baia Mare – an art center famous for its school of painting – he became first known due to paintings labeled as constructivist and his happenings, being classified among the neo-avangard Romanian artists during the seventies. Even though his first solo show in Rome (1969) had been a success, one of his silver medaled sculptures was included in the Fuji Museum collection in Tokyo, and his wooden sculptures were appreciated by the American artist and Brâncuși scholar Athena Tacha Spear, his real recognition abroad begun with Joseph Beuys' remarking that he was a 'genuine artist' ("Endlich, ein Künstler!") when Olos presented his concept of the Universal City and drew his module on a blackboard at one of the Free University seminars in Kassel, in 1977. Consequently, Beuys included the blackboard with the drawing in his "Das Kapital" shown in the main pavilion of the 1980 Venice Biennial. Olos's six-month teaching at the "Justus Liebig" University in Giessen, his successful performances, solo shows in Wickstadt and Giessen and later on in the Netherlands, made him realize that his work and ideas could have a better audience abroad. Thus, also due to the political turmoil in Romania after 1989, the artist moved his residence in the south-west of (Germany), continuing to exhibit in his native and neighboring countries. In the last decade of his life, finally recognizing his importance as an international artist, he was honored in his country of birth with a diploma, an anniversary show in Baia Mare and another one in the Brukenthal Contemporary Art Museum in Sibiu. In the autumn following his death, the curators of the Timișoara 2015 International Art Encounters exhibition showed his work in a special gallery. But only the posthumous extensive exhibition at the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Bucharest (May 2016 – October 2017, curator Călin Dan) offered an insight into the variety, extent, and quality of his work, setting the basis of the future development of his generous, inclusive constructive concept of the Universal City. Reticent to sell during his lifetime, there are still few state (among these about 30 in the Baia Mare Art Museum) and private collections owning his work, the greatest number being still in the possession of the estate curated by Plan B Gallery. The latest art fairs – in Madrid, Armory Show in New York, ArtBasel in Switzerland and ArtBasel in Hong Kong – have shown an increase in museums' and collectors' interest in his work, and the 2018 autumn show in Brâncuși's workshop at the Pompidou Center in Paris will mark the real acknowledgment of the importance of his work.

Early life[edit]

Childhood[edit]

Mihai Olos's family roots[1][2] are connected to the picturesque county Maramureș from north-western Romania. The ethnographic zone of his birthplace Ariniș (its older name being "Ardihat") is that of the sub-Codru (sub-forest) zone, connected with the culture of wood. If geographically the village is situated close to the central point of Europe, historically it is on the borders of the ancient Dacia, on the limes (limits or borders) of the Roman colonization, with some Celtic remains still visible in some circular stone crosses still extant also in the churchyard of the artist's birthplace. The recent archaeological discoveries have brought up remains of an important neolithic culture as well. The inhabitants are proud of their noble origins certified in the Maramureș "Diplomas", of their contribution to the development of nation building. Their opposition to denationalization during the Austrian-Hungarian Empire and the Vienna Diktat, and, with less success, during the years of the totalitarian regime have to be remembered as well. They are also proud for having contributed to the formation of the national language, with the oldest codex of written language found in a monastery from the region.

Mihai, the second son of a Romanian family, was baptized after his father known as "Mihaiu Florii Vilii" in village because there was another unrelated family also called Olos.[a] The artist was proud of his father's maternal family being related to George Pop de Băsești, a politician and president of the Transylvanian National Party (1905–1919). Still, while elaborating his future concept of universal city, he liked to connect his family name to the word's meaning in ancient Greek, i.e. "universal" or "total".

His mother Ana, coming from the Borșa family (or clan) of noble origin, was born in Poiana Codrului, in the full of mysteries zone of wood culture. Among the inhabitants of Poiana Codrului there were also German settlers, employed in the glass factory. His mother's blue eyes and fair hair might suggest also a Germanic ancestry.

Mihai's childhood had started as happily in a still unaltered natural and cultural environment with archaic roots as concerns the organization of the homestead, interior decoration of the home, the authenticity of the household object, customs and faith.

Since his father was most of the time away selling cattle at fairs, the baby boy spent his time with his mother and in the company of the village women. He saw them at work and witnessed their gatherings where sewing, spinning or other household activities were accompanied by singing, the reciting of folk poetry, the telling of tales. The secret practice of charms and witchcraft was still alive those days. The boy with an excellent memory and beautiful voice learned everything he could from the women and in no time became their favorite, imbued with all their knowledge. From his three years older brother and the village boys he learned their games and the making of hair balls, wooden toys, musical instruments from reed or corn stalks, of tree bark or young offspring, wooden skates or even sleighs. His father's being a tradesman influenced him in making rosewater and sell it to the girls in the village. Later on he wrote the girls' letters to their lovers in the army or composed little poems, drew images and texts for their wall-cloths for a modest return. Taking the cattle to the pasture, participating in the farm work from sowing to harvest and the preparation for the next crop, he was also involved in the rural rites around the year. From time to time, when the cattle fair happened to be in their village at crossroads, he was a witness to men's stories, those of the tradesmen coming also from other counties. He learned from them communication skills and the love of conviviality and this whetted his appetite to explore the world.

His early childhood, as he recalled it in his stories, appeared less marked by the war or the experiences of the Transylvanians who had to leave their homes during the Second Vienna Award. Living in his child's closed universe, at that time he was unaware of what was happening in the rest of the world. His father hadn't been conscripted to go to war. No one from the family died on the battle fields. The only tragic event he remembered was that one of his uncles coming home from the war died the day after his arrival and his daughter went after him.

The changes in the family's fate came after the war when, according to the Percentages agreement the country fell under the Soviet influence. The falsified elections of 1946, the forced abdication of the king at the end of 1947 and the establishment of a communist regime affected the child through their consequences. He remembered his father's loss of all the money he had earned selling cattle due to the 1947 currency reform. With the family's shaken material status, the two sons had to become their father's helpers in the everyday chores, whether working in the field or taking care of animals. Going to school and joining the community of the other children from the village came as a compensation. Starting school attendance at six, due to his interest in learning while seeing his elder brother' progress, Mihai became a dedicated pupil, determined to learn and discover all the secrets hidden in the world of books. Even if this period changed his orientation from the traditional multifaceted visual and oral culture towards what McLuhan call "the Gutenberg Galaxy", the archaic archetypal elements of folk culture and mentality would company alter on the artist in his encounters with the western urban culture.

Secondary school in the provincial town of Baia Mare (1953–1956)[edit]

A radical change in Mihai's life happened on 11 September 1950, when his mother died in childbirth, a death he never forgot. Their father's remarriage came as another shock to the boys and Mihai's elder brother, Vasile, was the first one to run away from home, followed by Mihai in 1953. Without any material support from home, the boys had no right to receive a scholarship because of their father's refusal to join the collective farm in the village. So they had to take their lives in their own hands. Mihai begun to teach private lessons and during the school holidays worked as a courier at the local newspaper. Learning the "ABC of journalism", he was sent to the countryside as a cub reporter, meeting various categories of people. This experience served him later on, when writing for the press and giving a theoretical grounding to his theories about art and the concept of the Universal City.

Substitute teacher in Oaș (1956–1959)[edit]

After graduating high-school and with his experience in private tutoring, Mihai applied for a teaching job.[1] The school was in a remote village in Oaș, Pășunea Mare. The zone had a specific ethnographic character, with extremely proud people who still practiced the vendetta. The women wore vividly colored skirts and scarves. The men used to wear on the top of their head a little straw hat embellished with beads. They were renowned woodcutters but there was no land good to farm. Poor eaters but great drinkers they would not accept a refusal when they offered a drink to their guests. Mihai got lodging for free in the house of violinist ("ceteraș", from the name of the violin called "cetera") and as a young school master he often accompanied the violinist to wedding feasts and round dances, playing the contra. The dances were full of rhythm, the singing with hollers, shriek, piercing interventions. Later on he will practice this kind of shriek singing – hollering – many times in his life, making himself remarked. For the young man who was not even seventeen when he arrived there, it was a capital experience from many points of view. With the permanent presence of death as he could have been killed if interfering in their feuds, this period could be compared to an initiation rite. As these remote villages from Oaș had also served as refuge for many fine intellectuals belonging to the former regime, these political refugees were the first to make known to him the names of the great Romanian writers never mentioned in school or those of important European or American authors and artists.

The gains of the years spent in different places from were counterbalanced by the harsh conditions of life and the poverty of the villagers. The improper living conditions and the poor diet affected the feeble young man's health. The occasion to leave was offered by the newly founded teachers training colleges all over the country and he chose to go.

Student in the cultural capital of Transylvania (1959–1963)[edit]

Advised by the intellectuals he had met and befriended in Oaș, he chose to go to Cluj, the cultural capital of Transylvania, instead of going to a closer town, such as Baia Mare. The years spent in Cluj, first as a student in the teacher training college then in painting section of the newly founded pedagogical institute, were decisive for his career. More important than the educational institutions he had attended, it was the cultural milieu in Cluj. The city had impressive buildings and churches, a national theater, a philharmonic, a long academic tradition, with various higher educational institutions, humanities, arts, music, a medical school of world renown, an excellent polytechnic, a wonderful botanical garden and a marvelous university library, important literary magazine. There were also the great professors and artists populating the town and these institutions, though some of the great personalities were still prosecuted. Among these were the great poet and philosopher Lucian Blaga who had been given a humble job at the university library and, the more visible for his patriarchal appearance, prose writer Ion Agârbiceanu. The city was accommodating thousands of students coming from different parts of the country, some of them, like himself, born in peasant families and determined to become intellectuals according to the traditional Transylvanian respect for learning.[b]

As much as he would have wished to become a student at the "Ion Andreescu" art academy, it had been impossible for him to survive without any material support during the six years of study required there. Nevertheless, he was lucky to have at the pedagogical institute a good professor of art, Coriolan Munteanu, renowned painter of churches, who recognized his students' personality and did not bridle their independent spirit with academic rules.

With his health problems aggravating, Mihai, like many other students, was lucky to be interned for long periods of time at the university clinic's student "preventorium". There, he got not only treatment but escaped from having to provide for himself. Other advantages were the presence of the doctors, some of them great intellectuals, and the contact with a variety of interesting or picturesque patients, among whom there were also some hiding from prosecutions. These counterbalanced the daily presence of death as TB was still an incurable disease, the use of streptomycin being only experimental.

The artist relates about a night in a moment when he had given up all hope to get well, depressed after his brother's death by drowning, in May 1962. In despair he decided to enjoy the remaining time exploring the city's night life, eloping from the ward and climbing over the fence surrounding the garden. The waiters in the restaurant offered him drinks and food for free on condition he entertained their clients singing the way he had learned in Oaș. He used to return to the preventorium secretly before dawn and sleep off his tiredness during the day. Whether due to these escapades or the use of streptomycin, he got well to the doctors' and nurses' amazement. His escape from death had the subtext of a Faustian pact allowing him to pursue his artistic destiny.

Settling down in Baia Mare, first trip westward, and first shows (1963–1968)[edit]

The Baia Mare Artistic Center in the sixties[edit]

After his graduation in 1963, he was hired as a teacher of painting at the so-called "popular" art school in Baia Mare, with night classes for art amateurs from different walks of life. The school was another project of the regime to educate people but also keep them busy and under surveillance. Even though this job was not at the extant art school in town, it gave the young painter more freedom and time to work during the day and prepare for the annual art shows where he had shown his paintings also as an undergraduate, since 1962.

An exhibition catalog from 1966 shows who were those who held the power to direct the local arts after the dissolution of the old traditional painting school. The president of the jury was sculptor Géza Vida, People's Artist, and laureate of the State Prize, with a privileged political status as a former participant in the International Brigades during the Spanish civil war. The jury members were: graphic artist, Paul I. Erdös, laureate of the State Prize (a Holocaust victim), painter Lidia Agricola, laureate of the State Prize (in her youth connected with the illegal communist party, widow of a painter victim of the Nazi's), and the older painter Andrei Mikola, Emeritus Artist who had studied in France. The others were the director of the local art museum, the representatives of the regional and county committee for culture and art, two so-called art critics with no special studies in the field of art, and finally a younger painter Traian Hrișcă, who had studied at the Bucharest art academy. Besides the artists already mentioned, among those who participated in the regional show in 1966, there were two other sculptors: Ștefan Șainelic and the now forgotten Maria Gyerkö, 12 graphic artists with 27 works, some of them, like Nicolae Apostol, Zoltan Bitay later better known as painters; 12 painters besides those mentioned, with 38 paintings, the best known being Iosif Balla, Alexandru Șainelic, Iuliu Dudás, Traian and Mircea Hrișcă, Ileana Krajnic, Augustin Véső, Imola Várhelyi, Ion Sasu from Satu Mare, and Natalia Grigore from Sighet.

After what he learned in Cluj about the Romanian modern artists and western art, the impressionism enjoyed by the local public did not suit the young artist. Neither did the official style of "socialist realism" imposed by the party as meant to glorify the new building sites and the achievements of the workers and peasants in the country appeal to him. But Mihai Olos was not the only one to disagree with the party's directions. The younger painters who had closer connection with western art were also discontent with the outdated style and the themes officially imposed. Thus, on the occasion of the Hungarian master Barcsay Jenő's visit to his native village Nima, near Cluj, at Augustin Vésö's initiative, a group of young artists simply kidnapped the painter and brought him to see their work. Mihai Olos was among those who met him.

A window opened westward[2][edit]

In the autumn of 1964, the young teacher of amateur artists fell in love with Ana, one of his pupils. She was a teacher of English at the local Pedagogical Institute whose father owned carpenters workshop in Timișoara that would provide him with frames and panel for his paintings and logs for his sculptures. Raised in the still patriarchal village community Mihai considered having a family and offspring as a condition of personal fulfillment. Moreover, meeting a young woman bearing his mother's name took it as a good omen. The parents' wedding gift was a Trabant, a much despised car brand those days and was left for the time being to rust in the street. So the young couple's honeymoon was spent as a train trip to Hungary and Czechoslovakia. In Budapest, they visited the art museum, impressed by the collection of Egyptian art, and, more important, they visited Jenő Barcsay's studio. The old master, a great admirer of Brâncuși's art, was already acknowledged as a great artist. He became world-famous especially due to his monumental Anatomy of the Artist translated into various languages. He was then working on a project to decorate the national theater in Budapest and showed them his sketches. But the real highlight of the journey abroad was an exhibition of modern art in Bratislava, with works of painters well known to the artist from albums but with the original paintings seen for the first time: Braque, Klee, Derain, Picasso a.s.o. The most impressive experience in Prague had been the visit to the ethnological museum Náprstek, with its excellent collection of primitive art.

This first trip abroad, even if in the Soviet zone, strengthened the artist's determination to travel westward. For this he had to become known and find supporters among the critics and the leaders of the Painters Union in Bucharest. Still, he did not desire to move to the capital for had the conviction, coming from what he knew about Brâncuși's art, that he had to keep close to his roots and the folk traditions of the county where he was born.

After becoming a member on probation of the Romanian Artists Union he got the right to rent a studio, and being married he could apply for an apartment in one of the newly built blocks of flats. Moreover, marriage and the birth of children would entitle the artist to get a passport to visit countries in the West.

Constantin Brâncuși – Master Model and "Recommander" to Critics[edit]

Mihai Olos was only seventeen when the great sculptor died in Paris and he must have heard the rumors about the communist government's refusal to accept Brâncuși's studio and bring home his work. Thus the artist's inheritance remained to the France whose citizen he had become a year before his death. Mihai Olos must have read also the articles published by the art critics Barbu Brezianu and Petru Comarnescu about the sculptor. Reading Brâncuși's biography, the young artist was impressed by the similitude with his own life-story: orphan at an early age (though it had been Brâncuși's father who had died), he ran away from home when he was eleven; he had a beautiful voice, he had suffered of tuberculosis and feeble health; he was fond of company, sang well, had been admired and loved by women etc. Moreover, Mihai realized that when he left his beard grow there was a shocking resemblance between him and the great sculptor, a resemblance he stressed wearing white folk garments and making people observe this similitude. The great sculptor's work – especially his birds and the Endless column – had been inspired by elements of folk carvings. Exploiting the folk art Mihai so well knew, with its abstract symbolism, seemed the best source of inspiration to circumvent and counteract the officially imposed style. Nevertheless, avoiding to become just an imitator of Brâncuși's model, Mihai Olos had to find some original element becoming his own. If Brâncuși had found inspiration in the wooden pillars from Oltenia and the wooden birds on pillars representing the soul of the deceased in country churchyards, Mihai remembered the combination of wooden pillars from the architecture of the churches in Maramureș and discovered an ingenious miniature replica of these wooden structures, replacing the little wheel at the end of the wooden spindles used by women when spinning. Moreover, some of these miniature structures at the end of the spindles had pebbles in the middle which made a rattling sound while the woman was spinning.

His admiration for Brâncuși's personality and art made Mihai Olos approach those who had known and written about the master and who would recognize his physical resemblance to him as a guarantee of his also becoming a great artist. The most important among these Brâncuși scholars was art critic Petru Comarnescu living in the capital city who – after a long period of prosecution for having been member, together with Mircea Eliade, of a right-wing group of intellectuals – got back the right to publish under his own name, during the mid nineteen-sixty's political thaw. The first great show of notice he organized was that of Ion Țuculescu's paintings which had no connection with socialist realism, an exhibition he will itinerate in the United States.

Mihai's trips to Bucharest, multiply and Petru Comarnescu includes him among the young artist deserving to be encouraged. The critic not only accepts him in his home with the other young artists, but after testing him to see whether he deserves his confidence, receives him as his friend, lets him sleep on the couch in the entrance hall, allows him to look at his art collection, his books, to read some of the letters he used to get from his friends living abroad, among them Eugène Ionesco, Mircea Eliade, Emil Cioran, as well as other members of the Diaspora.

The desire to exhibit in Bucharest became even stronger for the artist when the Baia Mare art museum opened a group show of Bucharest painters: Spiru Chintilă (born 1921) from an older generation, who had had a solo show in Baia Mare in 1959, Mihai Danu (born 1926), Ion Pacea (born 1924) and Ion Gheorghiu (born 1929). If Chintila's paintings hinted at cubism, Gheorgiu and Pacea had both, among other paintings, landscapes from Italy, as they had represented Romania at the Venice Biennial in 1964.

First shows: figurative, abstract, and stained-glass paintings (1965)[edit]

In order to exhibit in Bucharest, the artist had to show his work in his home town. Since 1962, while still a student, Mihai Olos had been present with his work in all local and regional collective art shows in Baia Mare. The first of these was in the company of graphic artist Cornel Ceuca. As its modest catalog shows, it was under the patronage of the Plastic Artists Union, and was opened at the Regional Museum in Baia Mare, in the summer of 1965.

As seen in the exhibition catalog,[3] Mihai Olos had on show 12 paintings in oil, most of them square (around 50x50). He chose themes that permitted abstract representations like "Archaeology", "Fire place", "Reel", "Homage". But also paintings with themes from the country-side, like "Village band", "Women from Lăpuș County" etc. Even his women's portraits were far from realistic. Besides his oil paintings, there were also 11 small dimension stained-glass paintings imitating the technique of the folk icons still to be found in villagers' houses and old churches. Though religious themes were banned those days of official atheism, he still dared to hint at his source by entitling one of them "Biblical". Others of Mihai Olos' paintings represented a series of children's games from the countryside. The following one man show was in Borșa and another in Baia Mare, without printed catalogs.

In 1965, he made his first abstract wooden sculpture he entitled "The secret of the heart" inspired from the joints in the local wooden architecture and the rattling wooden knot at the end of the spindle that will later on become the module for his "Universal City". Though not accepted by the jury, he succeeded to put his sculpture in one of the showrooms promising a prize to anyone succeeding to dismantle the sculpture. But no one succeeded.

The Brâncuși Colloquium in Bucharest (1967)[edit]

An important or rather crucial event in the young artist's life was the Brâncuși Colloquium organized in Bucharest in 1967, ten years after the great sculptor's death in Paris. Since the International Association of Art Critics acted as a partner, its then president Jacques Lassaigne was invited to attend. Besides him, the most important critics of the master's work had come to Bucharest. Among them were: Werner Hofmann from Vienna, Palma Bucarelli, Giuseppe Marchiori and Carlo Giulio Argan from Italy, Carola Giedion Welcker from Switzerland. Still none of the Romanian art critics from the diaspora – among whom we should mention Ionel Jianu – had been invited.

To honor this occasion, the Romanian Artists Union opened various exhibitions with the work of young artists. Mihai Olos had been included with some of his paintings on wood panels, in the group of thirteen artists whose work was shown at the "Kalinderu" art gallery. Critic Dan Grigorescu sees the group as a generation of "very young" artists, and lists the participants: Henry Mavrodin, Șerban Gabrea, Barbu Nițescu, Ion Bănulescu, Mihai Olos, Gabriel Constantinescu, Carolina Iacob, Adrian Benea, Paula Ribariu, Mircea Milcovici, Horia Bernea, Florin Ciubotaru, Ion Stendl and Marin Gherasim. Other groups of artists were shown at the more visible Dalles art gallery and at the Art Museum, as one can learn from Ion Frunzetti's review.[4] Olos had been invited together with other young artists to the reception Petru Comarnescu offered at his home, 10 Icoanei street. Carola Giedeon Welcker mentioned the event in her introduction to Comarnescu's book on Brâncuși, published after the critic's death.[c] On Comarnescu's advice, Olos offered three of his paintings on wood as gifts to critics Welcker, Buccarelli, Giulio Argan.

The presence of the Italian art critics inspired the young artist, who had reached the age when Brâncuși had left the country, to take his first trip west to Italy. It had been the destination Brâncuși himself had had first in mind, though his destiny took him first to Vienna, then to Germany and finally to Paris. But before showing his work abroad, Mihai Olos was expected to exhibit in the capital of his home-country.

In a letter dated 1 November 1967, Petru Comarnescu was informing his protégé about some Swedish art critics intending to organize an exhibition in Stockholm. They were selecting young artists and therefore visited various shows and young artists' studios. In the same letter Comarnescu was advising the young artist to continue to work in the abstract-folkloric style, because the critic's firm conviction was that the complementarity of the folkloric elements and modernism in Brâncuși's work was the secret of his greatness and success. There are also hints to Olos' planned exhibition in the capital.

Travels, Works, and Shows (1968–1974)[edit]

Since his first solo show in Rome, it would be difficult to separate the artist's life from his work for all his experiences serves to the development of his art. In the same way, the different forms of art, painting, sculpture, decorative or experimental art work develop almost simultaneously, most of them concerned with the development of his module, the knot, at the basis of progressions that should lead to materialization of his future project of the Universal City.

First solo show in Bucharest (1968)[edit]

Local or Transylvanian critics began to write about Mihai Olos' art beginning with the first shows of his work in Maramureș. His inclusion among the 13 artists shown at "Kalinderu Gallery", had been an incentive to Petru Comarnescu's and other critics to publish in Bucharest art magazines about his work, while his presence at the Brâncuși Colloquium imposed him to public attention. This reputation helped him to open his first one-man show at a central art gallery on Magheru boulevard in Bucharest, in January 1968.

There were 26 oil paintings with different themes (the best known among them: "Dance from Oaș" and "Pipers"), most of them abstract. There were also 37 mixed technique paintings on wood, and 5 banners hinting at church ceremonials. One of the paintings included in the catalog represented a stylized crucifixion.[d] The show was a success with quite a number of critical articles in the press, not only in Bucharest but also in the provinces, among the authors, besides Petru Comarnescu, being sculptor Ion Vlasiu, art critics Olga Bușneag, Eduard Constantinescu, and younger critic Radu Varia who will become one of his friends.

The same year he had four sculptures exhibited at the Triennial of Milan. Unfortunately, the show was devastated by rioters and it was closed down. Nevertheless, the artist succeeded to recover his sculptures. This success encouraged the artist to apply for a passport in order to visit Italy as a tourist.

Visiting the 1968 Venice Biennial[edit]

His frequent trips to Bucharest, since the time he had been a student, and his contact with various people while he had been teaching in Oaș, some of these already in the surveillance files of the secret police, the much feared Securitate, and especially his contact with the foreign participants who attended the Brâncuși Colloquium brought the young artist also to the secret police's attention. Thus it was of almost impossible for him to get a passport to go abroad.

But one of their family's friends, writer and critic Monica Lazar, sent a letter asking one of her friends in Bucharest who held a high position in the ministry of foreign affairs to support the artist's application for a passport. Still he artist received the permission to leave the country only a months after their baby daughter's birth, in July 1968.

Mihai Olos left for Italy just a days before the Warsaw Treaty's troops (except Romania and Albania) invaded Czechoslovakia on the night of 20–21 August. The most important event for his artistic career was his visit of the 34th Venice Biennial. He was happy to lay hands on the bulky second, corrected, revised and amplified edition of the catalog that had been printed in August at Fantoni Artegrafica Venezia, its "copertina" reproducing the Biennial's manifesto "ideato da Mario Cresci".[5] The "catalogo" opened with its president Giovanni Favaretto Fisca's Preface and G.A. Dell'Aqua's "Introduzione" he had no need to read then but which are important in retrospect.

Both texts underline the renewal of the oragnizers' vision since the first after-war edition in 1948. The organizers were under the pressure of many protests and the actual changes in society and art. The artists could not anymore br classified simply into two categories, "figurative" or "abstract", as some of them came with completely new innovative practices in art (XXIII).

The organizers had intended to show in the central pavilion, on the one hand, the four major representatives of the first Italian futurismo – Giacommo Balla, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo and Gino Severini, Boccioni having been on show in the previous edition. On the other hand, they had prepared a large international show e titled "Linea della ricerca contemporanea – Dall' Informale alle nuove strutture". This had to show the most representative artists, exponents of the successive tendencies from 1950 to 1965. "Informal" had been used with the widest sense of the word referring to "materials, corporeal language, 'gesto', signs and 'scrittura'; new abstractionism referred to "space, geometry, color"; perceptive structures: rhythm, movement, light. The new figuration, starting from expressionism and surrealism, included figures, grotesque forms and visions; objectual realism: things, persons, signals; the new dimensions of space: object-paintings, environmental work, primary structures a.s.o. Furthermore, they had wanted to include minor art forms such as ceramics, or other forms of visual arts, like stage design, photography, advertising and industrial design, poesia visiva etc.

Moreover, they had intended to invite four contemporary architects – Franco Albini, Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph, and Carlo Scarpa – to show their specific way of imagining and configuring space.

Mihai Olos had not recorded in writing his observations about the Biennale, probably thinking that he would never forget what he saw, one could just suppose the huge visual impact the show had on him. Some representative artist's names appearing in the catalog were: Francnis Bacon, Josef Albers, Jean Arp, Willi Baumeister, Alexander Calder, Marcel Duchamp, Lucio Fontana, Hans Hartung, Arshile Gorky, Roy Lichtenstein, Kasimir Malevich, Robert Motherwell, Ben Nicholson, Claes Oldenburg, Eduardo Paolozzi, Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, Antonio Tapies, Gunther Uecker, Viktor Vasarely, and among others Wolf Vostel with his "happening". To these, one should add what the 34 national pavilions contained. The Italian Pavilion presented 23 artists, most of them considered of no great importance by the contestants.[6] Mihai Olos was happy to see that among those who introduced the artists in the catalog were the names of the two critics he had met in Bucharest the previous year. Giulio Carlo Argan wrote about Mario Nigro whose "Dallo 'spazio totale'" (1954) with its gridwork had caught his eyes. While Palma Buccarelli was enthusiastically introducing Pino Pascali, as the "wonder child" of Italian art, with his use of combinations of traditional and new industrial materials (for example "steel wool" or plastic brushes) in achieving some unusual pieces of artworks like his huge "worm" of the mushroom-like "Pelo" (Hair) and "Contropelo" (Counterhair) – an evident reference to the American "tribal" love-rock musical.

Bucarelli showed the connection between "homo lundens" and "homo faber" in Pino Pascali's personality and underlined the artist's ironic titles illustrating his love of puns. She considered him to represent the new artists protesting against the consumerism of the society and the commodification of art. The tragic death of Pino Pascali in a motorcycle accident at the beginning of September attracted even more attention to his work and he became the Biennial's laureate. Touched by Pascali's tragic death, Mihai Olos will include in the catalog of his show in Rome the mirror image of his poem written in homage to the Italian artist.

The 1968 Venice Biennale is remembered also due to the students' protests and the organizers involving a great number of policeman and agents to keep order, that led to other protests, refusals to open certain shows, closing individual shows (Gastone Novelli, Achille Perilli or Nicolas Scöffer) or national pavilions (e.g. the Swedish) or individual gestures of protest like turning the face of the paintings towards the wall and showing the back of the painted canvases.

Romania's commissar had been Ion Frunzetti and the artists on show: Virgil Almășanu (b. 1926) with 32 oil paintings, Octav Grigorescu (born 1933) with 36 drawings, tempera and water color paintings, and sculptor Ovidiu Maitec (born 1925) with 11 wooden sculptures and a bronze, each of the artists with two black and white photos in the show's catalog. If Almășanu's abstract paintings were nothing new to the Mihai Olos. But Ovidiu Maitec's use of wood for his sculptures must have made Olos think of this successfully relating to rural architecture in Romania. Maitec's heavy winged "Bird" intentionally different from Brâncuși's birds resembled the massive hinges of a double gate, or to a magnified wooden hinge held together by a wooden nail. Maitec's use of wood most probably gave Olos the idea to make himself some wooden sculptures there in Rome, though smaller in dimension, for his show at Felluca Gallery.

First international solo show: Rome, "Felluca Gallery" (1969)[edit]

Arriving in the Italian capital, Mihai Olos got accommodation and the possibility to work at the Romanian Academy's subsidiary, where another artist, Petru Achițenie was spending the time of his scholarship. Olos came with letters of recommendation to the members of the Romanian diaspora received from Petru Comarnescu. Among these, journalist Horia Roman and his daughter Cecilia (who became his closest friends), painter Vasile Drăguțescu, journalist Mircea Popescu and others. But Olos met and visited also Italian personalities in Romance studies like Rosa del Conte and others. As it is well known this was the period of students movements and it was a hard time for academics.

In just a period of some months, the young artist succeeded to set up his one-man show at "Felluca" art gallery. The well-organized opening – that could be considered a performance, as the artist clad in a hairy peasant's coat from Maramureș ("guba"), sang folk songs and hollered – proved to be a great success. The Romanian Embassy was represented by its Cultural Ataché, there were actors from the Cinecitta, artists, critics, diplomats, and, naturally, members of the Romanian diaspora. The show consisted in small stained glass paintings and small wooden sculptures whose forms already show the structural elements of the module for his universal city. Comments on the show appeared in the most important dailies and weeklies in Rome, such as Momento-sera, Il Tempo, Il Giornale d'Italia, Il mesagero, This Week in Rome. Among those who signed articles, besides the gallery owners, Derna and Vittore Querrel, had been also Lorenza Trucchi, an important art critic.

Besides his visit of Biennial and the promotion of his work, his stay in Italy had a profound impact on the artist. Starting with all that could be seen in Rome, he succeeded to go also to other important Italian cities. He visit the most important museums, churches and historical monuments, and saw the most famous Italian artists' work. He also met or at least saw the work of the important artists of the day. It is no wonder that he did not hurry to return home. But the news from home – his father's being prosecuted for not having joined the collective farm and his wife being questioned about the date of his return – made him shorten his stay.[e]

Why did he not remain in Italy for good? Ceaușescu's refusal to join the Warsaw-pact troops at the invasion of Czechoslovakia had changed the perception of Romania in a favorable way in the eyes of the west. Thus the artist accepted the idea to return home in the hope that there would be other opportunities to leave the country.

Great expectations at home. Installations: "Dacia" Cinema and the Youth Club, Baia Mare (1969–1970)[edit]

Returning home with the glory of his success in Rome echoed in the Italian press and his own articles, Mihai Olos was commissioned with the decoration of a huge wall on the first floor of the entrance hall of "Dacia" cinema. His decorative work covering a surface of 120² m. was a visually impressive sequence of convex square aluminum plates, with inserts of smaller round mobile elements, alluding to Vasarely's op art as well as to his stables and mobiles. (The upper freeze was decorated with sculptor Valentina Boștină's work also with metal pieces.) During the nineties, the ones who bought the building tore down their work apparently with an intent to renovate the building, something they have not done.

Mihai Olos was also commissioned with the interior decoration of the local youth club. The decoration was, on the one hand, of rural inspiration with wooden tables and benches covered with red and black woolen rugs woven in the countryside, alluding to the striped front and back apron-like decorative pieces covering women's skirt in the village, called "zadie". But the most spectacular part of the decoration were the huge round mirrors which had been made in the glass factory from Poiana Codrului (his mother's birthplace), reflecting and multiplying the space and giving depth and mystery to the rather small room. But this work has not been preserved either.

As a recognition of these achievements he received the Plastic Artists Union's youth prize and, in 1970, he was included – with a short presentation and the black-and-white reproduction of one of his painting's on wood – among the artists in the album with 1111 reproductions of Romanian painter's work edited by four critics.[7] His work was characterized as a blending of the real and fabulous, as an expression of his tumultuous character, reminding of Rouault's expressionism. Still, the roots of his art were traced back to his native Maramureș, with the intention to modernize folk art.

Though cautioned by Petru Comarnescu to keep a low profile, the artist had confidence in his tremendous energy and capacity to impose his talent. Unaware of the "tall poppy syndrome" of those who could not accept other people's being successful, the artist believed that his show in Rome was just the first of a series of coming great successes. Believing that he could show at home and impose some of the new forms of art he had witnessed in Italy, he was expecting too much from the provincial public.

First happening / installation: "25" (1969)[edit]

His first happening entitled just "25" (that could be classified also as an installation), was on 24 August 1969, like an ironic counterpoint to the parades celebrating the country's "liberation" from fascism by the Soviet Army. For Olos' symbolic event was evidently meant to make people think about the victims of the recent floods in the country. It consisted in showing in the local art gallery[f] two long flat metal vessels resembling baking tins, one containing water, where the visitors were supposed to throw coins (reminding of the Fontana Trevi), and the other with mud and green nettles. It is evident that he was echoing Pino Pascali's 32 m2 di mare with trays painted in blue he had seen in Italy. The event was not commented upon in the press and his interview with a local reporter showed his disappointment at people's reactions.[8] It contained also a quite subversive reference to Constantin Virgil Gheorghiu's book The 25th Hour, a novel that had been published in French translation in 1949, and had inspired Carlo Ponti's film (1967) directed by Henri Verneuil and starring Anthony Quinn and Virna Lisi.[g]

Going Eastward via The Soviet Union to Japan. The Osaka "Expo" and Japanese architecture (1970)[2][edit]

The decoration of the movie theater came also with a financial gain that allowed the artist to pay his ticket for an excursion to Japan organized by the communist youth's travel agency. The same decision had been taken by his colleague Nicolae Apostol and both of them were accepted to join the group visiting the 1970 Osaka Expo.

The idea to visit Japan had come to the artist's mind already in 1967, when he met and interviewed anthropologist Tadao Takemoto who came to visit Maramureș. But now, the opportunity to see the Osaka International Fair came also with the thrill to see an event similar to the Montreal Expo that had celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Canadian confederation almost simultaneous with the Bucharest Brâncuși Colloquium. As seen in the articles in the Artists Union's monthly Arta Plastică (12/1967) commenting on both events, the idea of associating sculpture with architecture was surfacing as a new idea in both events. in Bucharest, it had been as an echo of Brâncuși's work, while in Montreal it was suggested by the Expo's general theme: "The human being and the Environment". The Romanian reporter commenting on the Montreal show mentioned Tingueley's kinetic sculpture and Niki de Sain-Phalle's huge figures in the French Pavilion. The illustrations showed sculptures by Henry Moore, Calder etc., other images gave an idea of the futuristic sites of the new cities with the branching modular structures of the Canadian Moshe Safdie's "Habitat '67", the experimental "Lego architecture" (nowadays a favorite among children's toy boxes), the idea of "ephemeral cities", and the presence of Buckminster Fuller in Montreal. All these made the artist look forward to this trip to Japan.

Among the novelties the Osaka Expo showed in the field of architecture were the Telecommunication Pavilion, Midori-Kan's "Astrorama", the image of the multidimensional world, the Toshiba Pavilion, and the Takara Group's "The Joy of Being Beautiful". As he would later on mention it to Joseph Beuys at Kassel, Krebs had also there his laser sculptures. But what captivated the artist's attention in Japan more than the Osaka Expo was the use of wood in architecture, not much different from that in the Romanian villages. The artist will publish his observations in an article with his "super-expressions", upon his return home.

Going to Japan by train via the Soviet Union allowed the group to visit also Leningrad and Moscow and the art museums there. It was also an opportunity to travel through the Russian taiga and Siberia, experiences which enriched the young artist's perception of the world.

His connection with Japan will be resumed later on when with other Romanian artists he will send some of his work to art shows in Japan and one of his wooden sculptures would get a prize.

Being informed – the provincial artist's secret. Approaches to urbanism[2][edit]

The artist who in his childhood had instinctively absorbed the message what his father's raising him above his head meant, became aware first of all that residing in a provincial town, before starting his way out, he had to know everything possible about the international art scene. During the period of thaw after Gheorge Gheorghiu- Dej's death, there was the possibility to subscribe to various publication from the neighboring Soviet-block countries and the artist could read or at least look at the name of the artists and their work in art magazines like the Hungarian Müvészet, Vytvarne umenie from Czechoslovakia, the embassy's' publications like La Pologne, the German Prisma, or the American Sinteza. If from England one could receive only their communist party's the Daily Worker, one could freely subscribe to a series of French publications. Among these the hebdomadaire Les lettres françaises came with weekly fresh information in the field of art, with Jean Bouret's "Sept jour avec le peinture" and theoretical articles or even special issues dedicated to an artist with colored reproductions of his work. Less informative about the arts, the monthly Europe had also special issues dedicated to artists. A special art magazine like Cimaise or Arts-loisirs were more expensive and more difficult to subscribe to. One could also find in bookshops albums printed in France and could buy Albert Skira art albums of the greatest artists or collections of texts referring to a certain art trends, like Surrealism, for instance.

The Romanian Arta plastică was bringing information about what was happening in the country but also news of the art-world abroad. The monthly Secolul 20, whose director since 1963 had been art critic and later president of the art critics international association, Dan Hăulică, would contribute to inform on what was happening in contemporary culture. As the period of the thaw was encouraging translations in the field of arts as well, the Meridiane Press started to publish an important collection of books and also anthologies with texts on currents in art as well as syntheses.

On the occasion of their first trips abroad, the artist and his wife would always bring new art books and magazines. Thus his wife returned from her tourist visit to England with subscriptions to Burlington Art Magazine and Studio International, one of its issues containing a review of Athena Tacha's Brancusi's Birds[9]. This had been the starting point not only of the negotiation for the translation of the book but also of a long friendship. The American professor and sculptor of Greek/Vlach origin became the main provider of American art magazines (Art International, Art and Artists, Art in America and Artforum). Later on the artist would receive from Germany the similarly well informed Art Kunst.

Even if the Romanian art magazine Arta plastică was the most important source of information about what was happening in the country, another important monthly world literature magazine, Secolul 20 whose editors (like artist Geta Brătescu or its later editor-in-chief art critic Dan Hăulică), tried to bring into their readers attention what was actually happening in the western culture. This was also a period when publishing houses offered their readers translations of the most important books, at least those accepted for the party's cultural policy.

Among these books one of the most important proved to be an anthology of texts by Le Corbusier compiled so as to give a general image of the architect's life and work, introduced and translated by architect Marcel Melicson, published by Meridiane art press in 1971. The very first page of Le Corbusier's presentation caught the artist's attention. It showed that although the French architect had no diploma and academic training in the field, he succeed to become more than that, "the only one who was in the same time architect, urbanist, poet, painter and writer, desiring to be a complete human being and artist, following the example of the Renaissance citizen-artists".[10] In his introduction, Melicson, himself a well informed architect, attracted his readers' attention on the fact that Le Corbusier was not the only a great architect of the period contributing to the formation of a new architectural vision. He provided names neglected by the "usual" dictionaries, such as: Adolf Loos, Walter Gropius, Frank Lloyd Wright, Alvar Aalto or Mies van der Rohe.

Among the artist's notes from the beginning of the 1970s – for in his "imitatio Brâncuși" he used to put down his own cogitations, there is one idea he had pondered much upon. It gives the definition of a provincial artist as one who knows everything about the other artists but nobody knows him. (During the years he would discover that this is true – or at least it was true in those years with no access to information on the Internet – for all artists who did not live in great art centers. While preparing his show in the Nijmegen art gallery in 1989, his exhibition's curator, Van den Grinten, will show him a catalog published in 1964, with the work of an older Dutch sculptor, Erwin Heerich (born 1922). Among Heerich's experimental pieces, Mihai Olos will discover two with the cube, made of paper in 1962, identical with his own experimental forms.[11])

The year 1970 came with a great loss for the artist: his great supporter, art critic Petru Comarnescu's death. But he had already become "visible" in the artworld of Bucharest and especially among the literati. The artist capable to not only to sing but also recite from Romanian or other great poets for hours had been accepted as one of them, a remarkable poet himself still more an artist for he had no ambition to collect his poems in a volume.

If the artist was remarked at first sight for his good looks, unconventional clothing either with original pieces from the countryside, or just inspired from the folk costumes from his region of birth or Oaș, sometimes tailored by himself, in conversation he would impress his partners with information coming from various fields, his wide knowledge of poetry – for he first had wanted to become a poet –, arts and philosophy, and also his interest in sciences. Since he had learned to read, books played an important place in his life. While a student, he not only visited art shows and museums but spent time in libraries as well, reading art history, studying reproductions in albums, including books on the index from which he made notes for later on.

Having read the Romanian Andrei Oțetea's general presentation of the Renaissance in 1964,[12] the translation of Giorgio Vasari's lives of painters and sculptors,[13] having seen albums with reproductions, Mihai Olos had gone to Italy well informed about the Italian Renaissance and its artists. After his return he felt a need to confront his own impressions with those who wrote about Italian art. The first book he read was Jakob Burckhardt's comments on Renaissance,[14] Irina Mavrodin's translation of Élie Faure's history of Italian art,[15] Bernard Berenson's book on Renaissance artists[16] and others.

Nevertheless, what had made the greatest impact on Mihai Olos was Paul Valéry's Introduction to Leonardo da Vinci's Method. He read the Romanian version[17] dwelling upon the text as well as on the marginal notes. He read with the same curiosity books on modern art. Giulio Carlo Argan's essays on the fall and salvation of modern art[18] that came with the presentation of important artists, and also Jean Grenier's essayas on contemporary art. In the Meridiane Press' collection of currents and synthesis, the young artist found the Romanian version of Nicolas Schöffer's Le nouvel esprit artistique. The chapters on the three stages of dynamic sculpture, spatial dynamism, open structures, events and suspense, the suppression of the object and the illustrations representing Schöffer's cybernetic tower and other projects were of great interest to Mihai Olos. He was only happy to insert his own mark, a drawing that represents his essential structure, onto an open space in the chapter on cybernetics.

Even though for the artist living far from the capital there were no hopes to find sponsors or get funding for environmental sculptures, he could still receive at times invitations to send of his work to art shows abroad. Thus, Olos had the chance to send one of his sculptures to Japan, where it got into the collection of the Fuji museum. Still, the artist felt the need to get personally in contact with the art world abroad. He was also frustrated because it was difficult to find among the artists living in Baia Mare partners to discuss with, in comparison with the four or five large cities in the country, like Timișoara etc. where young artists had succeed to have groups sharing their wish to change traditional arts and experiment.

Following the changes in the country's cultural policy after Ceausescu's return from his visit to China in 1971, the artists would begin to use, like many of the writers in the country, the so-called "double language". It was meant to evade the more and more severe censorship, but was perfectly understood by those who knew how to read between the lines. For the Romanian artists the adoption of other forms of art, many of them experimental, in consensus with the young critics, was in order to evade the officially accepted "socialist realism". Alexandra Titu's well-researched book on the experimental arts in Romania after 1960 (published only in 2003)[19] gives a full-extent image of the phenomenon.

It would be mistaken to think that Mihai Olos was content "to serve" just one teacher or master. His natural curiosity and his fight against the provincial complex had led to his determination to know as much as possible about the ideas haunting him and made him look for several sources of information. Among these, with the effect of a master class, was Bruno Munari's Design e comunicatione visiva, whose first version Olos must have seen in Italy and whose fourth edition he had received from a friend in 1972.[h] The book had been written as a practical guide with many illustrations, resulting from the lectures Munari, visiting professor at Harvard, had given at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, in the spring of 1967. It had been already about computer graphics, modulation in four dimensions, Retrogardia, Avanguardia, optical effects, ambiguity, visual codes, impossible figures a.s.o.. Olos was shocked by the similitude between the module he had discovered and the serialization of cubic structures by two less known Dutch artists, Jan Slothouber and William Graatsma – a visually less impressive structure than the one the rattling spindle's knot had inspired him. Nevertheless, the principle that admits the proliferation of the module represented more evidently the idea of unity as well as that of inclusion. But he found also another type of combination of the basic elements, with the ends of the elements pointing outside, with a mouth-like opening or the end of the joint representing a cross. Other illustrations in Munari's book were representing experiments from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, or images of pavilions from the Montreal Expo of 1967.

The Romanian artist's interest in architecture made him approach the group of architects working in Baia Mare who had at their department office their "internal" informative publications. They willingly shared them with the young artist who had already seen with his eyes some of the great art monuments of the world.

In 1972 he succeeded to buy Michel Ragon's book about the world history of architecture connected to modern urbanism. Its second tome was referring to practices and methods during 1911–1971.[20] The chapters presenting the most interest for the artist were those referring to urbanims and the recent approaches to it. In a sub-chapter referring to urbanism in the European "peoples democracies" (Poland, Romania, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia), Olos found references to the "industrialization of architecture" using prefabricates in the building of large living ensembles, like districts Floreasca-Tei in Bucharest, the ensemble from Balta-Alba, built for 10,000 inhabitants, or architects N. Kepes' and N. Porumbescu's plans of urbanism, and those of Sully Bercovici in architecture. Among the new buildings from the Romanian capital, Ragon mentioned Ascanio Damian's grand round exhibition hall and the building of the State Circus by Porumbescu, Rula, Bercovici and Prunku. Cesar Lăzăresu's name appeared referring to the Mamaia open air theater. In another chapter Ragon mentioned Martin Pichis' research prospective.[20]

A sub-chapter in Ragon's book of great interest to Olos was the one connecting urbanism and the environment, human geography, biology, ecology, zoology etc. This was again an opportunity to remember the wisdom that governed the organization of the rural communities' life so as to preserve the purity of their resources and avoid damaging the ecological balance. The artist became aware of the long-time danger of the pollution with exhaust gases from the local chemical combine. This brought about, later on, his more vocal protests against this chemical pollution as well as against the "pollution" of the traditional rural culture with implants from urban culture by the former peasants who commuted to their jobs in towns or cities. In order to attract people's attention to their connection with the ancestral agrarian culture from their country, besides the conferences he started in the countryside, Olos projected two new happenings meant to attract the participants in a kind of initiation ritual which, instead of telling them, would involve the participants emotionally and "show" them things connected both to their work but also to their ancient culture.

Second happening: "Gold and Wheat" (Herja, 1972)[edit]

His success in Italy got the dimension of a legend in Baia Mare. His decorative work in the local "Dacia" movie theatre, the echoes of his trip to Japan, his presence in the local press with articles as well as with poems in local anthologies, his studio open to his friends, admirers and visitors from all over the country and sometimes foreigners, made Mihai Olos visible in the eyes of the local community and gave him also a prestige in the eyes of the apparatchiks. At that time, most of these came from modest urban or rural backgrounds, some of them still catching up with their secondary school studies. Still, looking back at those times, it seems that the artist had the power of a mentalist or magician to convince the local authorities to accept his idea of a quite unusual or rather singular happening, the event "Herja" Mine (November 1972), then just mentioned in the local press, but with a wide national echo in later years.

The happening, at about 500-meter underground in the pit of the mine Herja, had been programmed by the artist during the miners' exchange of shifts. It consisted in the 25 ingots brought over from the Baia Mare subsidiary of the National Bank and set on a table covered with wheat grains in the form of the structure become now his module, Olos constructive pattern of the "universal city". It is difficult to imagine the event's impact on the miners since besides the artist's glosses on Herja (the name of the mine), there was just another evasive article in the local press.

Apparently, it was a homage paid to the miners who had to work in the darkness under earth to bring up to light the precious metal and having never seen the ingots kept in banks. It was symbolically connecting their work to the agrarian myth of the grain and its cycles between death and life. Nevertheless, the event's subtext was certainly a hint to the many political prisoners who had worked and perished in the mines from the region during communism.

The way he used to experiment with the same idea as transposed in different media, the artist gave a painterly representation of the happening some years later. In comparison with the somewhat linear disposition of the miners in the photographic representation, in the painting the miners become a more compact group around the central point with the ingots. The strange thing is that the miners with the protection casks on their head recall the figures of the Italian futurists Boccioni and Marinetti from a 1915 photograph representing them in motorcycling costume and protective glasses on their caps, reproduced in Michel Ragon's book.[20] It is difficult to tell whether this be just a coincidence sending the researcher just to the event's photographic representation, or whether it was intentional or just a trick played by the artist's remarkable visual memory.

Land art / Intervention: "The Earth" (Cuhea, 1973)[edit]

In the meantime, the artist had been experimenting with other materials besides wood – like foam, paper, hay, transparent Plexiglas, a.s.o.– in reproducing the same structure or variations of the module. One of those pieces made of foam for instance, in 1973, accommodates in the middle his little son and another module is held up by his daughter. The same motif will appear in the late '80s, in a painting with a woman and a man (a hint to Adam and Eve, or possibly to himself and his wife) entrapped among the 6 "clutches" of the totalitarian structure.

As an acknowledgment of his module originating in the folk architecture from Maramureș, Tribuna României – a multilingual monthly advertising Romanian realities to readers living abroad and severely criticized by the diaspora for its beautifying Romanian realities – published an article on Olos, entitled "Maramureș – a starting point of the planetary city".[21] Nevertheless, his being advertised in this context, could have made the artist suspect in the eyes of the Romanians from the diaspora. And this is probably why he would be received with reserve by the members of the Romanians around Monica Lovinescu in Paris when visiting Paris.

Exploring the "negative" of the structure, the artist prepared a new happening, actually an experiment in land art entitled concisely as "The Earth", in village Cuhea, in 1973. The digging up of earth so that the negative of the structure should remain in the pit, was another attempt for the artist to synchronize his art with that of the other experimental artists in the country and abroad. Though the personal legend he attaches to this earth-work later on, is his feeling of premonition regarding his father's death.

Some of his paintings dated also 1973, now in the collection of the Baia Mare Art Museum, illustrating the event bear the title of "Spatial construction I", "Spatial construction II", and "Ritual".[22]

During the same year 1973, he will accompany philosopher Constantin Noica (who had accepted in 1971 to become the artist's elder son's God father), on a ritual trip to Maramureș, reporting on their discussion in the local daily.

The 13th Colloquium of the "Mihai Eminescu" Society from Freiburg in Baia Mare[edit]

His knowledge of the region, seen also his articles on folk art and the folklore published in the local press made of Mihai Olos an excellent guide and discussion partner for visitors coming from the capital or abroad. One of these was Benjamin Suchoff from the Bartok Institute in New York, another the Japanese anthropologist mentioned before. This is why Mihai Olos had been asked to be the secretary of the folklore section in the conference the "Mihai Eminescu" society from the Freiburg University had organized together with the University of Iași, the Philology departments of the Suceava and Baia Mare Institutes of higher education. The theme of the symposium was "Maramureș, a model for the culture of south-eastern Europe".

Besides the local participants, the organizers invited to Baia Mare first-rank personalities of the Romanian academia, such as ethnologist Mihai Pop, professor in Bucharest, ethno-musician Harry Brauner a.s.o.. Among those coming from Germany were professors Klaus Heitman, Paul Miron and his assistant Elsa Lüder, and some of their students. While accompanying them on their visit to the countryside, Mihai Olos convinced them of his wide range of knowledge in various fields and need to be given new opportunities to further study. Besides, the university of Freiburg had a geographically favorable position to let him visit also the neighboring countries.

Art interventions:[i] "A Statue Ambles through Europe" (1974–1988)[edit]

At the end of 1974, with two small children and a pregnant wife, he was allowed to leave the country on a round trip, taking him through Yugoslavia, to Italy, France, Germany, Switzerland and Austria. And this had been also the starting point of his ritual journey that lasted some years "A Statue Ambles through Europe".

The "declared" intention of his action-journey entitled "A statue ambles through Europe"– a parody of "a ghost ambles through Europe", the well-known phrase from Marx and Engels' Manifesto of the Communist Party – was "to confront" a scepter-sculpture made by Mihai Olos with the "values" of the European art from different countries, including also the happenings or incidents on the road. Nevertheless, the idea of these interventions could have been inspired by a political event. In March 1974, when Ceaușescu, besides being the Party's Prime secretary, in his wish to have absolute power, made himself elected also as president of the republic. Most of papers in the country published the photograph of the moment when the presidential scepter was handed over to him. The news had an international echo and Salvador Dalí sent a telegram to congratulate (most probably with an ironic intention) the communist leader for transforming the symbol of monarchy into that of a republic. Dali's telegram was republished in the party's daily and reproduced in other newspapers as well. The photographs with Mihai Olos raising his wooden scepter-sculpture above his head during his "interventions" on the road could be viewed as alluding to the leader and his travels abroad. Nevertheless, a later painting in which the artist represented the presidential couple dressed in peasants costume, with the leader holding as scepter Mihai Olos' sculpture with the knot of the spindle, has been interpreted as a compromise.

The action continued along the years, the artist's following journeys including the meetings at Rochamps, Vesuv, Olimpos, Acropole, the Arta and Bosporus bridges, Cappadochia, Gordion, Gaudi's works in Barcelona and "the meeting" with Joseph Beuys, though never shown in its entire development, and ended with the picture taken at the rune stone from Felling in Denmark (1988).

Paris – an unfulfilled promise[edit]

The artist's travel to France and his contact with all that Paris could offer in the field of art, including his beloved painters Matisse, Picasso, Braque etc. and most of all to see Brâncuși's heritage meant a lot to him. Traveling via Germany, Olos arrived in Paris with Constantin Noica's recommendations finding accommodation at one of the philosopher's cousins. Nevertheless, he was lucky to find in Paris the famous historian of religions and writer Mircea Eliade, to whom he had been recommended by Petru Comarnescu some years before, when the critic organized the exhibitions promoting Țuculescu's paintings in the United States. Mihai Olos met the most important representatives of the diaspora as introduced to them by Mircea Eliade. Among them, Emil Cioran, Moninca Lovinescu and Virgil Ierunca, the couple whose programs broadcast by Free Europe or articles in the French or diaspora press were harshly critical as regards the Romanian leader's policy,[23] unmasking the impoverishment of the population, the control of their possessions and income with new trials and imprisonments. The response to these broadcasts had been the sending of agents to threaten the members of the diaspora and Monica Lovinescu being almost killed in 1977 by a bomb hidden in a package addressed to her.

Among the most important for the artist meetings in Paris had been his discovery of the work of two Romanian philosophers, Ștefan Odobleja – whose Consonantist Psychology in two volumes published in 1938 and 1939 he brought home to study – and Ștefan Lupașcu[24] whom he visited and whose theories about the psychic system and the importance of contradiction and antagonism, the structure of the system of systems etc. had a great impact on the artist's thinking.

Theories on art and first recognition as a conceptual artist[edit]

"Rostirea" ("the utterance") as concept and constructive principle

Still in the sixties, during philosopher Constantin Noica's visit to a friend in Baia Mare, Mihai Olos had been introduced to him and became one of his admirers, though not one of the "philosophers' pupils". Nevertheless, the artist found in Noica's references to what he called the "Romanian philosophical utterance" a biblical term he will use from now on, i.e. "rostirea" (utterance),[j] instead of the common and restrictive term "language", in insisting upon the primordiality of the spoken/oral aspect. Olos used the word "rostirea" in its meaning of "joining", corresponding to the combining of concrete elements so as to form a whole. This was also an opportunity for the fond of word games artist to engage into finding a pair to the word, namely "rotirea"–"turning round"–, suggesting the circular movement of the spindle. Thus, if "rostirea" was referring to the elementary structure he had discovered in the little wooden knot on the wheel at the end of the spindle representing an atomic image of the world, "rotirea" was referring to its revolving around, reproducing the planets' motions. Though the artist knew about the philosophy of structuralism, he preferred to adhere to constructivism, and its connection to architecture. Nevertheless, "Rosturi" will become title of some of his paintings with "progressions", during the sixties.

The knot – key element of Olos' art[edit]

If in his childhood the future artist had unconsciously registered the colors, forms and structures present in his environment – the geometrical elements in the carpets and rugs and also in the decorative elements, on the geometrically cut items of clothing, in religious paintings and architecture – in his first wooden sculpture he reproduced the knot-structure of the spindle consciously of its artistic value. Later on he will discover or consciously look for such structures in other artists' work. In this respect, his contact with Italian art had been extremely important. He had become more attentive to details and the geometrical elements appearing in figurative painting as well. His readings at his return home will only clarify his observations.

Since his graduation, as a teacher at the people's art school and as occasional speaker at the people's university in Baia Mare, Mihai Olos continued to publish in the local press about folk art, comments on artists' shows, interviews and book reviews, along with his "glosses" on art, informing the readers about contemporary art and about his own projects. One of these glosses had been given a generous space in the local daily's supplement and was entitled "Urbanism".[k] Seen in retrospect, it has an evident relation to what was going on in the country in the process of forced urbanization. But the idea of the "universal city" the artist will later on call "Olospolis"– that may be compared to the western "counter-architecture"– had been locally accepted due to its exulting a symbolic structure having its origin in the ancient peasant wooden architecture.

In Ragon's book, in the chapter about a new type of architecture referring to new techniques, he read about A. Foppl's old notion of "reticular structure" (1882), Graham Bell's experimenting in Canada with "floating" structures composed tetrahedrons, and about Robert Le Ricolais' essay on reticular systems in three dimensions, as a new language in architecture. The tridimensional, or bi-, tri- or quadri-directional structures realized of different materials have a knot which is the key element of spatial structures. The idea, as important as it had been, brought no fame and recognition to the unknown French architect (b. 1894) though his influence on avant-garde architecture should be considered as important as that of Buckminaster-Fuller's who emigrated to the US in 1951, to teach at the university of Pennsylvania. Olos was also impressed by Le Ricolais' use of topologie and mathematics. Besides stressing the importance of the node / the knot as basic constructive module, there were some convincing illustrations like maquettes for spatial and mobile cities by Yona Friedman, Ph. Lucien Hervé, Walter Jonas's maquette for an "intrapolis" or Isozaki's and Ph.O. Murai's spatial structure,[20] references to electric urbanism, Inis Xenakis' publishing his project for a "cosmic city", and even Dan Giuresco's inclusion with his "Alpha city",[20] that became important sources for further meditations.