Drugs and sexual consent

This article contains close paraphrasing of a non-free copyrighted source, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-007-9031-0 (Copyvios report). (August 2023) |

Drugs and sexual consent is a topic that discusses the impacts of drugs on sexual activity that lead to changes in sexual consent. Sexual consent is the voluntary agreement to engage in sexual activity, which is essential in preventing sexual violence.[1] Consent can be communicated verbally or nonverbally and should be freely offered.[2] However, drug use, particularly psychoactive drugs (i.e. alcohol and some illicit drugs) that alter mental processes, can affect people’s decision-making and consent communication ability, potentially impacting the autonomous aspect of sexual consent.

The definition of sexual consent, "agreement to engage in sexual activity", highlights that willingness is equivalent to consent and desire is equal to "wantedness", though they are not always related.[3] Therefore, individuals can provide consent for sex even if they do not necessarily desire it, making the boundary of “sexual consent” unclear.[4] The situation complicates the legitimate judgment of sexual violence, blurring the line between consensual sex and rape when the accuser is severely intoxicated and cannot clearly express disagreement.[5]

Most studies on drug and sexual consent are based on self-reports that emphasize the psychological and sociological aspects, while the direct biological mechanisms remain largely unexplored. However, the indirect physiological effects of drugs on sexual consent, such as impaired cognition and judgment, may lead to changes in sexual behavior and affect sexual consent.

Psychological and sociological aspects[edit]

A study demonstrated three ways drugs could affect sexual consent in psychological and sociological aspects.

Increased perceived sexual autonomy[edit]

Drugs could improve the autonomous aspect of sexual consent, thus raising the tendency of the user to engage in both desired and undesired sex.[3]

Firstly, drug use may diminish cognitive issues that keep people from engaging in sexual behaviors.[3] This includes removing impediments to sexual activity, such as social conventions, religious beliefs, and sexual guilt. For some individuals, drug-taking is necessary for them to participate in homosexual sex, which frees them from a sense of taboo.[6]

Through expanding user's sexual boundaries and limitations, drug also improves people's participation in different varieties of sex, including those that are previously undesired.[3] Some claimed that they would consent to have sex that they would not try in sobriety,[7] for example, BDSM, role play, and use of sex toys.[3]

Individuals on drugs reported feelings of intimacy, trust, love, and a strong desire to have sex with multiple sexual partners.[3] Due to the symbolic nature of closeness and trust, drug use may also boost a desire to engage in sex without using condoms.[3] Once the effects of the drugs wear off, these emotional attachments may fade away, leading to emotions of regret.[8]

Others' perception of drug users being sexually available[edit]

Individuals on drugs claimed to be viewed by others as sexually available, that is, more likely to provide consent to engage in sexual activities.[6] Two fundamental presumptions appeared to be connected to this impression.[3] (1) People believe using drugs makes it simpler to persuade others to engage in sexual activity as drugs have a reputation for promoting sexual pleasure, making men perceive women on drugs as "horny" and more sexually available.[6] (2) Drug users are also thought to be prepared to offer sex trade for drugs, implying a sense of reciprocity between these transactions.[3] Despite their initial reluctance, women often provide sex in return for drugs,[3] with 57% of opiate users reported receiving drugs or money in return for sex.[9] Unlike buying drugs with cash, the sex-bought method is often implicit with unspecific pricing standards.[3] People are less likely to relate implicit exchange with predicted bad outcomes, so they are more likely to encourage the behavior than explicit trades.[3]

Minimize the capability to communicate consent[edit]

Several studies have found that significant drug use can impair or change judgment, resulting in irrationality and overexcitability during drug-related sexual conduct.[10] This might be due to people focusing on achieving orgasm regardless of their sexual partner's experience.[11] Some drugs impair sexual awareness, making it harder to make sexual decisions.[3] The meaningfulness of consent made by a high individual on the verge of passing out was challenged.[12] People on drugs are more “suggestible”. In other words, they are more willing to obey their sexual partner’s orders.[3]

Drugs also impair the capability to communicate sexual consent.[3] Those who used marijuana reported an inability to speak out or oppose sexual behaviors though cognitively reluctant.[13] Narcotics can also impair muscular control, making it difficult to indicate no through body language.[7]

Biological activity of drugs[edit]

Although it is commonly believed that recreational drugs act as aphrodisiacs and serve as preludes to sexual activities, their specific mechanisms remain to be explored.[14] Various models have been composed to imitate the drug kinetics of these drugs on sex. However, most drug-sex study data were collected from small sample interviews and self-reports.[15] Social environment, drug dosage, duration of use, and user characteristics are other factors that should be considered.[16]

The section focuses on discussing several most used recreational drugs. Methamphetamine, which has more direct studies on its biological mechanism of sexual consent, is also explained.

Alcohol[edit]

Alcohol is a depressant and a psychoactive drug that can alter human behavior.[17] The views of alcohol on sexual consent vary significantly. Alcohol is frequently seen as a significant sexual facilitator, disinhibitor, and possibly an aphrodisiac.[14] It often precedes and facilitates sexual activity in social settings, encouraging people to be more receptive to sex.[16] Similar to other drugs, people who drink are often seen as being more sexually available and more seductive after drinking.[3][18]

However, other studies suggest excessive alcohol may have negative effects on sex. Alcohol can interfere with the release of sexual hormones, such as testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone, possibly stifling sexual arousal.[14] It can also directly affect blood flow or other physiological processes in sexual organs. It has been hypothesized that alcohol's depressive effects on the central nervous system (CNS) may cause erectile dysfunction, decreased vaginal secretions, diminished sexual responsiveness, and other sexual dysfunctions.[19][20] The physiological response to sex decreases with alcohol consumption in women, despite increasing self-reporting sexual desire and ability to reach sexual orgasm.[21] In addition, the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which blocks impulse transmission, is most prominently increased by alcohol.[15] High blood alcohol level increases its activity in the spinal cord potentially causing drowsiness,[15] making it more difficult to communicate sexual consent.

Marijuana[edit]

Marijuana, also known as cannabis, is of the highest consumption in the recreational drug market.[22] 70% of marijuana consumers viewed it as an aphrodisiac and 81% increased sexual delight and satisfaction.[23] However, limited physiological evidence indicates that it stimulates sexual desire or improves sexual function.[15] Most evidence suggests the link between the two is indirect. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive component of marijuana, has a similar structure to the neurotransmitter anandamide. THC can target the hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex to affect memory formation and induce hallucinations.[15][24] It also influences feelings of pleasure, sensation, and other cognitive functions.[25] In addition, high THC dosage impairs basic motor control and reactions.[25] The ability to communicate consent after initiating sexual activities decreases while intoxicated. However, the mechanisms of the self-reports effect of marijuana to promote sexual enjoyment are still unclear. This stimulation could result from a general improvement in sensory experience.[15]

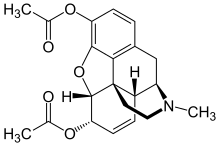

Opioid[edit]

Opioids, also known as heroin, are the world's second most popular drug.[23] They are CNS depressants that relieve pain and induce sedation.[26] Some users describe a rush of euphoria after using the drug similar to sexual orgasms.[15] Due to the ability to delay orgasm, muscle relaxation, and analgesic effects, opioid is also used in self-medication for sexual dysfunctions such as premature ejaculation in males or dyspareunia in female.[15] However, long-term opioid use can influence the neuroendocrine system, inhibiting gonadotropin-releasing hormones to decrease libido and lower testosterone levels in men.[15]

Previous research has been limited to self-report studies. However, opioid sedation can impair cognitive function,[27] potentially impairing judgment about sexual boundaries and consent. It can also alter pain perception and pleasure,[28] affecting drug-users' ability to assess their comfort level accurately during sexual activity.

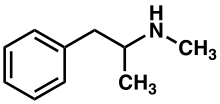

Methamphetamine[edit]

Methamphetamine (MA) is a potent stimulant impacting the CNS. From self-report studies, It has been found to enhance sexual desire, promote pleasure, and delay orgasm.[15] However, methamphetamine use is greatly associated with high-risk sexual behaviors and reduction in sexual inhibition.[29][30] Methamphetamine can increase the likelihood of engaging in atypical sexually behaviors, such as pedophilia, group sex, and same-sex intercourse among heterosexual individuals.[25]

One issue related to sexual consent concerns whether agreement is made under conscious conditions. Methamphetamine abuse is linked to neurotoxicity in the brain and has deleterious effects on cognitive processes,[31] for example, deficits in episodic memory, executive functioning, information processing speed, motor skills, and language abilities.[32] The impairment of cognitive ability could thus lead to diminished capability to provide informed and enthusiastic consent.

Furthermore, Methamphetamine users have been found to differ from non-users in high-risk behavior related neurocognitive decision-making processes.[33] This research reveals the weaker activation of the risk and reward-modulating regions in brains of casual drug users. As the system is responsible for handling risks and rewards, neurological differences suggest that during decision-making, methamphetamine users may be less concerned about the potential risks associated with a choice. Instead, they may focus more on the potential gains and immediate outcomes. This could explain why methamphetamine users may engage in high-risk sexual behaviors or have sex with partners who they would not in sobriety. They only consider the immediate pleasure rather than long-term risks.

Animal studies confirm that methamphetamine and sexual behavior activate the same neurons in the CNS responsible for motivation and reward.[34] Methamphetamine and sexual behavior are considered as "rewards" that trigger the release of dopamine, causing feelings of pleasure and satisfaction. These pleasurable feelings in turn acts as a motivation again, encouraging people to compulsively seek natural rewards. In sum, this co-activation of neuronal populations suggests that methamphetamine use leads to compulsive seeking of natural rewards, in this case, sexual behavior, proving the drug heightens sexual consent autonomy.

Drug-facilitated sexual assault (DFSA)[edit]

Drugs do not only affect one's decision on sexual consent but also cause a loss of ability to express it. Date rape drugs including ethanol, benzodiazepines, gamma-hydroxybutyrate, and ketamine are frequently used in facilitating sexual assault.[35]

Ethanol[edit]

Ethanol is sometimes used as a date rape drug, as it can cause amnesia, impaired motor coordination, and mental confusion, all of which can aid the actions of sexual predators.[35]

Benzodiazepines[edit]

Benzodiazepines are medications used to treat anxiety, stress, and insomnia. When the drug binds to the GABA receptor, sedation and muscle relaxation occurs.[35] Flunitrazepam is a common benzodiazepine used in rape facilitation since it causes memory blackouts.[36]

Ketamine[edit]

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic often abused for its euphoric and hallucinogenic tendencies.[35] The drug could induce dissociation in the brain, which is the separation or disconnection in activities between the thalamus and limbic systems,[37] causing amnesia that facilitate sexual abuse.[38]

Gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB)[edit]

GHB have a chemical structure similar to neurotransmitter GABA. It is commonly used as a date rape drug due to its euphoric and CNS depressant effects[39] which can slow down brain activity. Additionally, individuals may experience poor concentration and confusion after taking GHB.[40]

Application[edit]

Drug-taking was found to impact the capacity to make sexual decisions, raise engagement in anal intercourse, willingness to have multiple sex partners, and decreased condom usage. This increases susceptibility to sex-related health issues and associated harms, including HIV and venereal disease.[41]

A key aspect of harm reduction is educating those who might use sex-related drugs about the consequences of doing so, and encouraging them to evaluate their possible sexual partners.[5] Public education about drugs and sexual consent could also lessen victim-blaming beliefs and increase social support.[3] Due to a lack of knowledge and education regarding sexual consent-related issues, bar industry employees have found it challenging to stop sexual harassment.[42] Implementing policies and prevention strategies could be aided by future education initiatives, like bystander prevention. However, many nightclubs claimed to have "zero-tolerance" drug usage policies, making it difficult to provide instruction without seeming to support drug use.[3]

References[edit]

- ^ "What Is Sexual Consent?: Facts About Rape & Sexual Assault". www.plannedparenthood.org. Planned Parenthood. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- ^ Hickman, Susan E.; Muehlenhard, Charlene L. (1999). ""By the Semi-Mystical Appearance of a Condom": How Young Women and Men Communicate Sexual Consent in Heterosexual Situations". The Journal of Sex Research. 36 (3): 258–272. doi:10.1080/00224499909551996. ISSN 0022-4499.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Smith, Lauren A.; Kolokotroni, Katerina Z.; Turner-Moore, Tamara (4 May 2021). "Making and Communicating Decisions About Sexual Consent During Drug-Involved Sex: A Thematic Synthesis". The Journal of Sex Research. 58 (4): 469–487. doi:10.1080/00224499.2019.1706072. PMID 31902239. S2CID 209895703.

- ^ Peterson, Zoe D.; Muehlenhard, Charlene L. (1 April 2007). "Conceptualizing the "Wantedness" of Women's Consensual and Nonconsensual Sexual Experiences: Implications for How Women Label Their Experiences With Rape". The Journal of Sex Research. 44 (1): 72–88. doi:10.1080/00224490709336794. PMID 17599266. S2CID 44423781.

- ^ a b Rumney, P.N.S; Fenton, R.A (18 February 2008). "Intoxicated Consent in Rape: Bree and Juror Decision-Making". Modern Law Review. 71 (2): 279–290. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2230.2008.00692.x. S2CID 145751301.

- ^ a b c Skårner, Anette; Svensson, Bengt (October 2013). "Amphetamine use and Sexual Practices". Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 30 (5): 403–423. doi:10.2478/nsad-2013-0035. hdl:2043/16082. S2CID 144254144.

- ^ a b Deimel, Daniel; Stöver, Heino; Hößelbarth, Susann; Dichtl, Anna; Graf, Niels; Gebhardt, Viola (December 2016). "Drug use and health behaviour among German men who have sex with men: Results of a qualitative, multi-centre study". Harm Reduction Journal. 13 (1): 36. doi:10.1186/s12954-016-0125-y. PMC 5148887. PMID 27938393.

- ^ Desai, Monica; Bourne, Adam; Hope, Vivian; Halkitis, Perry N (May 2018). "Sexualised drug use: LGTB communities and beyond". International Journal of Drug Policy. 55: 128–130. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.04.015. PMID 29801810.

- ^ Jessell, Lauren; Mateu-Gelabert, Pedro; Guarino, Honoria; Vakharia, Sheila P.; Syckes, Cassandra; Goodbody, Elizabeth; Ruggles, Kelly V.; Friedman, Sam (October 2017). "Sexual Violence in the Context of Drug Use Among Young Adult Opioid Users in New York City". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 32 (19): 2929–2954. doi:10.1177/0886260515596334. PMC 4740284. PMID 26240068.

- ^ Claire Van Hout, Marie; Brennan, Rebekah (17 June 2011). ""Bump and grind": an exploratory study of Mephedrone users' perceptions of sexuality and sexual risk". Drugs and Alcohol Today. 11 (2): 93–103. doi:10.1108/17459261111174046.

- ^ Opperman, Emily; Braun, Virginia; Clarke, Victoria; Rogers, Cassandra (July 2014). ""It Feels So Good It Almost Hurts": Young Adults' Experiences of Orgasm and Sexual Pleasure". The Journal of Sex Research. 51 (5): 503–515. doi:10.1080/00224499.2012.753982. PMID 23631739. S2CID 32043319.

- ^ Bourne, Adam; Reid, David; Hickson, Ford; Torres-Rueda, Sergio (March 2014). The Chemsex study: drug use in sexual settings among gay men in Lambeth, Southwark & Lewisham. London: Sigma Research, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. ISBN 978-1-906673-18-5.

- ^ Palamar, Joseph J.; Acosta, Patricia; Ompad, Danielle C.; Friedman, Samuel R. (April 2018). "A Qualitative Investigation Comparing Psychosocial and Physical Sexual Experiences Related to Alcohol and Marijuana Use among Adults". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 47 (3): 757–770. doi:10.1007/s10508-016-0782-7. PMC 5250581. PMID 27439599.

- ^ a b c McKay, Alexander (2005). "Sexuality and substance use: The impact of tobacco, alcohol, and selected recreational drugs on sexual function". The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 14 (1).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Peugh, Jordon; Belenko, Steven (September 2001). "Alcohol, Drugs and Sexual Function: A Review". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 33 (3): 223–232. doi:10.1080/02791072.2001.10400569. ISSN 0279-1072. PMID 11718315. S2CID 27215932.

- ^ a b Rosen, Raymond (1991). "Alcohol and Drug Effects on Sexual Response: Human Experimental and Clinical Studies". Annual Review of Sex Research. 2 (1).

- ^ "Is Alcohol A Drug?". Orlando Recovery Center. 28 March 2023. Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- ^ Jones, BT; Jones, BC; Thomas, AP; Piper, J (August 2003). "Alcohol consumption increases attractiveness ratings of opposite-sex faces: a possible third route to risky sex". Addiction. 98 (8): 1069–75. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00426.x. PMID 12873241.

- ^ Drugs: issues for today. R. R. Pinger (3rd ed.). Boston, Mass.: WCB/McGraw-Hill. 1998. ISBN 0-8151-2937-8. OCLC 37443525.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Miller, Norman S.; Gold, Mark S. (January 1988). "The human sexual response and alcohol and drugs". Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 5 (3): 171–177. doi:10.1016/0740-5472(88)90006-2. PMID 3070052.

- ^ George, William H.; Davis, Kelly Cue; Heiman, Julia R.; Norris, Jeanette; Stoner, Susan A.; Schacht, Rebecca L.; Hendershot, Christian S.; Kajumulo, Kelly F. (May 2011). "Women's sexual arousal: effects of high alcohol dosages and self-control instructions". Hormones and Behavior. 59 (5): 730–738. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.03.006. ISSN 1095-6867. PMC 3159513. PMID 21439287.

- ^ "WDR 2022_Booklet 2". United Nations : Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- ^ a b Halikas, James; Weller, Ronald; Morse, Carolyn (January 1982). "Effects of Regular Marijuana Use on Sexual Performance". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 14 (1–2): 59–70. doi:10.1080/02791072.1982.10471911. ISSN 0279-1072. PMID 6981694.

- ^ Abuse, National Institute on Drug (July 2020). "How does marijuana produce its effects?". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- ^ a b c Buffum, John (January 1982). "Pharmacosexology: The Effects of Drugs on Sexual Function – A Review". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 14 (1–2): 5–44. doi:10.1080/02791072.1982.10471907. ISSN 0279-1072. PMID 6126532.

- ^ Vella-Brincat, Jane; Macleod, A. D. (2007). "Adverse effects of opioids on the central nervous systems of palliative care patients". Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy. 21 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1080/J354v21n01_05. ISSN 1536-0539. PMID 17430825. S2CID 17757207.

- ^ Dhingra, Lara; Ahmed, Ebtesam; Shin, Jae; Scharaga, Elyssa; Magun, Maximilian (October 2015). "Cognitive Effects and Sedation". Pain Medicine. 16 (suppl 1): S37–S43. doi:10.1111/pme.12912. ISSN 1526-2375. PMID 26461075.

- ^ Fields, Howard L. (2007-05-01). "Understanding How Opioids Contribute to Reward and Analgesia". Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine. 32 (3): 242–246. doi:10.1016/j.rapm.2007.01.001. ISSN 1098-7339. PMID 17543821. S2CID 15293275.

- ^ Frohmader, Karla S.; Bateman, Katherine L.; Lehman, Michael N.; Coolen, Lique M. (1 September 2010). "Effects of methamphetamine on sexual performance and compulsive sex behavior in male rats". Psychopharmacology. 212 (1): 93–104. doi:10.1007/s00213-010-1930-8. PMID 20623108. S2CID 23790582.

- ^ Green, Adam Isaiah; Halkitis, Perry N. (2006). "Crystal methamphetamine and sexual sociality in an urban gay subculture: an elective affinity". Culture, Health & Sexuality. 8 (4): 317–333. doi:10.1080/13691050600783320. ISSN 1369-1058. PMID 16846941. S2CID 43474362.

- ^ Salo, Ruth; Nordahl, Thomas E.; Natsuaki, Yutaka; Leamon, Martin H.; Galloway, Gantt P.; Waters, Christy; Moore, Charles D.; Buonocore, Michael H. (2007-06-01). "Attentional control and brain metabolite levels in methamphetamine abusers". Biological Psychiatry. 61 (11): 1272–1280. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.031. ISSN 0006-3223. PMID 17097074. S2CID 14865032.

- ^ Scott, J. Cobb; Woods, Steven Paul; Matt, Georg E.; Meyer, Rachel A.; Heaton, Robert K.; Atkinson, J. Hampton; Grant, Igor (2007-09-01). "Neurocognitive Effects of Methamphetamine: A Critical Review and Meta-analysis". Neuropsychology Review. 17 (3): 275–297. doi:10.1007/s11065-007-9031-0. ISSN 1573-6660. PMID 17694436. S2CID 21174399.

- ^ Droutman, Vita; Xue, Feng; Barkley-Levenson, Emily; Lam, Hei Yeung; Bechara, Antoine; Smith, Benjamin; Lu, Zhong-Lin; Xue, Gue; Miller, Lynn C.; Read, Stephen J. (2019). "Neurocognitive decision-making processes of casual methamphetamine users". NeuroImage. Clinical. 21: 101643. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2018.101643. ISSN 2213-1582. PMC 6411911. PMID 30612937.

- ^ Frohmader, K.S.; Wiskerke, J.; Wise, R.A.; Lehman, M.N.; Coolen, L.M. (March 2010). "Methamphetamine acts on subpopulations of neurons regulating sexual behavior in male rats". Neuroscience. 166 (3): 771–784. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.070. ISSN 0306-4522. PMC 2837118. PMID 20045448.

- ^ a b c d Costa, Yanna Richelly de Souza; Lavorato, Stefânia Neiva; Baldin, Julianna Joanna Carvalho Moraes de Campos (2020-08-01). "Violence against women and drug-facilitated sexual assault (DFSA): A review of the main drugs". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 74: 102020. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2020.102020. ISSN 1752-928X. PMID 32658767. S2CID 220522090.

- ^ Kintz, Pascal (20 March 2014). Toxicological Aspects of Drug-Facilitated Crimes. Elsevier Science. ISBN 9780124167483. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- ^ Morse, Bridget L.; Morris, Marilyn E. (2013-06-28). "Toxicokinetics/Toxicodynamics ofγ-Hydroxybutyrate-Ethanol Intoxication: Evaluation of Potential Treatment Strategies". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 346 (3): 504–513. doi:10.1124/jpet.113.206250. ISSN 0022-3565. PMC 3876779. PMID 23814094.

- ^ Da Silva, Francisca Charliane Carlos; Dantas, Rodrigo Tavares; Citó, Maria d do Carmo de Oliveira; De Vasconcelos, Silvânia Maria Mendes; Fonteles, Marta Maria de França; Viana, Glauce Socorro de Barros; De Sousa, Francisca Cléa Florenço (2001-03-31). "Ketamina, da anestesia ao uso abusivo". Revista Neurociências. 18 (2): 227–237. doi:10.34024/rnc.2010.v18.8486. ISSN 1984-4905.

- ^ Busardo, Francesco; Jones, Alan (2015-04-13). "GHB Pharmacology and Toxicology: Acute Intoxication, Concentrations in Blood and Urine in Forensic Cases and Treatment of the Withdrawal Syndrome". Current Neuropharmacology. 13 (1): 47–70. doi:10.2174/1570159x13666141210215423. ISSN 1570-159X. PMC 4462042. PMID 26074743.

- ^ Abuse, National Institute on Drug (2018-03-06). "Prescription CNS Depressants DrugFacts". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- ^ Calsyn, DA; Cousins, SJ; Hatch-Maillette, MA; Forcehimes, A; Mandler, R; Doyle, SR; Woody, G (March 2010). "Sex under the influence of drugs or alcohol: common for men in substance abuse treatment and associated with high-risk sexual behavior". The American Journal on Addictions. 19 (2): 119–27. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00022.x. PMC 2861416. PMID 20163383.

- ^ Powers, Ráchael A.; Leili, Jennifer (7 December 2017). "Bar Training for Active Bystanders: Evaluation of a Community-Based Bystander Intervention Program". Violence Against Women. 24 (13): 1614–1634. doi:10.1177/1077801217741219. PMID 29332525. S2CID 24540584.