Double Shuffle (Canadian political episode)

| Double Shuffle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Event | Political episode in the Province of Canada in 1858 |

| Cause | Defeat of the Macdonald–Cartier government |

| Date | July 29, 1858 |

| Replacement | Brown–Dorion government installed and then fell |

| Date | August 2 to 5, 1858 |

| Outcome | Cartier–Macdonald government formed |

| Date | August 6 and 7, 1858 |

The double shuffle of August 1858 is the kind of event that persuades historians not to write about nineteenth-century politics. It depends on such an accumulation of period detail and constitutional arcana that making it plausible is like trying to explain the notwithstanding clause to a visiting Martian.

The Double Shuffle was a political episode in the Province of Canada in 1858. It began on July 28, 1858, when the coalition government of John A. Macdonald (Liberal-Conservative) and George-Étienne Cartier (Bleu) was defeated on a confidence vote in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada, concerning the location of the seat of government for the Province. The government resigned the next day.

The two opposition leaders, George Brown (Reform) and Antoine-Aimé Dorion (Rouge), formed a new government. However, Macdonald and Cartier were able to defeat the Brown–Dorion government in the Assembly on August 2, 1858. One factor contributing to that defeat was a statutory requirement that new Cabinet members automatically lost their seats on appointment, and had to stand for re-election in ministerial by-elections. Brown, Dorion, and the rest of their new Cabinet therefore immediately lost their seats in the Assembly. Those vacancies helped shift the balance of power in the Assembly in favour of Cartier and Macdonald.

Cartier and Macdonald were then able to form a new government, with the support of an influential independent member of the Assembly, Alexander Tilloch Galt. They took advantage of an exception in the statute which provided that a Cabinet minister who was appointed to a different position in Cabinet did not have to resign and seek re-election. Cartier and Macdonald appointed most of the members of their former Cabinet, including themselves, to different positions in their new Cabinet. The next day, they re-appointed some of them back to their old positions. For example, Macdonald had been Attorney General for Canada West in their previous Cabinet. For one day, he was the Postmaster General in their new Cabinet. The next day, he was again the Attorney General for Canada West. This "Double Shuffle" of the Cabinet was upheld by the courts.

The double shuffle had the immediate effect of keeping Macdonald and Cartier in power, even though their previous government had been defeated on a confidence measure just a week earlier. It also fuelled a strong personal animosity between Macdonald and Brown, who were already bitter political rivals. More long term, by highlighting the political instability of the Province of Canada, the Double Shuffle contributed to the Great Coalition of Macdonald, Cartier, Galt and Brown in 1864, formed for the purpose of seeking Canadian Confederation and ending the political deadlock in the Province of Canada.

Political situation in the Province of Canada[edit]

The Province of Canada was formed in 1841 by the union of the provinces of Lower Canada and Upper Canada. The two sections were significantly different in their linguistic, religious, and ethnic make-up. Lower Canada (called Canada East in the new province) was largely French-speaking, although with a considerable English-speaking minority. Most of the inhabitants were Roman Catholic. Upper Canada (called Canada West in the new province) was largely English-speaking, and mainly Protestant. The legal systems were different: Canada East used the civil law derived from France, while Canada West used the English common law. The two sections had their own court systems, and different school systems.[2][3][4]

There was a single Parliament for the province, composed of the elected Legislative Assembly, and the appointed Legislative Council. The Parliament passed laws for the entire province, but also laws which only applied to one section. Members from Canada East could vote on laws which only applied in Canada West, and members from Canada West could vote on laws which only applied in Canada East. Canada East and Canada West had equal representation in the Parliament, regardless of population shifts. These factors meant that formation of a government required substantial support from both sections. During the 1850s, four main political groups had emerged, two in Canada East and two in Canada West. The groups were not political parties in the modern sense, as there was not strong party discipline. There were also independent members of the Assembly, whose support might be necessary to keep a government in office.[2][3][5][6][7]

In Canada East, the two main groups were the Parti bleu and the Parti rouge. The Bleus, led by George-Étienne Cartier, supported the British connection, business and trade, and the ultramontane Roman Catholic church. The Parti rouge, led by Antoine-Aimé Dorion, tended towards republicanism, a suspicion of big business, and anti-clericalism. The Bleus tended to win a majority of the parliamentary seats in Canada East.[2][3][6]

In Canada West, the Liberal-Conservatives, led by John A. Macdonald, were a merger of conservative Reformers and the old Tory group. They had tended to hold a majority of seats in Canada West, until the election of 1857, when they came in second. Opposing them were the more liberal Reformers and Clear Grits, led by George Brown, who won the majority of seats in Canada West in the 1857 election. Brown was the publisher of one of the leading newspapers of Canada West, The Globe (forerunner of the Globe and Mail), which he used effectively to publicise his Reform policies. Brown's major campaign plank was to end the equal representation of Canada East and Canada West in Parliament, and instead adopt a system of representation by population, or "rep. by pop." While this proposal won support in Canada West, which had the larger population, it was largely opposed in Canada East, which had the smaller population. Rouges and Bleus both were opposed to the loss of political power which they saw in "rep. by pop."[2][3][6][8][9]

The Bleus and the Liberal-Conservatives generally had more common ground than the Reformers and the Rouges, and had been able to form coalition governments. However, the electoral support for the four groups was generally stable. That stability of electoral support for the different groups, coupled with the need for representation from both sections to form a government, contributed to overall political instability. Votes in the Parliament could be tight, and a government that lost a vote on a matter of confidence would have to resign. The tight political balance also meant that there was no single premier at the head of the government. Instead, there were always co-premiers, one from Canada East and one from Canada West, forming a coalition ministry.[2][3][8][10][11]

Fall of the Macdonald–Cartier government, July 29, 1858[edit]

Party standings[edit]

In the general elections in December 1857, Cartier led the Bleus to a majority of the seats in Canada East, but in Canada West, the Liberal-Conservatives under Macdonald had come in behind the Reformers, led by Brown.[9][12] Taken together, the Bleus and Liberal-Conservatives had enough seats to form a government, continuing the Macdonald–Cartier ministry, but the government's support in the Assembly was shaky in the 1858 legislative session. It remained in power through the support of the Bleus, but was generally opposed by a majority of the members from Canada West.[11][13][14][15][16][17]

In opposition, Brown began to send out feelers to Dorion and the Rouges, searching for common ground to build an alliance in the Assembly. To be successful in challenging the government, they would need to attract support from some of the Bleus and independent members from Canada East. During the course of the long session of 1858, the Reformers from Canada West and the Rouges of Canada East began to find common cause. What finally attracted support from some Bleus and independents was a long-standing, highly contentious issue: the location of the seat of government.[13][18]

Seat of government dispute[edit]

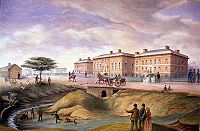

The Province of Canada did not have a permanent seat of government. The Union Act, 1840 gave the Governor General the power to determine where Parliament would sit in the Province.[19] By 1858, Parliament had met at various times in Kingston, Montreal, Toronto and Quebec City. Ottawa had also been suggested. The location of a permanent seat of government was extremely divisive, and the Macdonald–Cartier ministry was itself badly divided on the issue. Macdonald and Cartier feared that the issue could weaken the union itself. Governor General Sir Edmund Walker Head was similarly concerned that the issue had to be resolved if the province were to remain united.[16][20][21][22][23]

In the 1857 legislative session, and possibly acting on a suggestion from the Governor General, Macdonald and Cartier had proposed that Queen Victoria should choose the seat of government. The Legislative Assembly then passed an Address to the Queen, asking her to choose the permanent seat of government. The opposition members had strongly opposed this approach, arguing that it undercut the principle of local responsible government, by deferring the decision to London. In late 1857, the Queen chose Ottawa, at that time a small lumbering settlement, but with a centralised location on the border between Canada East and Canada West.[20][23][24][25]

Even though the Queen had chosen Ottawa, there was still opposition to that choice in Canada East and Canada West, as the four other cities all continued to have strong regional supporters. Brown and Dorion hoped to use that regional support for Montreal and Quebec City to attract Bleus and independents.[13][18][26]

Defeat of the Macdonald–Cartier ministry[edit]

In July 1858, the government introduced a motion in the Assembly to approve the construction of new parliament buildings in Ottawa. In response, the opposition introduced a series of motions critiquing the choice of Ottawa, culminating in a motion to reject Ottawa entirely. On July 28, the Assembly passed the opposition motion, 64–50, with some Bleu supporters of the Macdonald–Cartier government voting in favour of it.[13][16][27][28]

The Assembly finally adjourned at 2 o'clock in the morning. Macdonald, Cartier and the other members of the ministry met and concluded that they would treat the defeat on the motion as a confidence matter. The next day, July 29, Macdonald announced in the Assembly that the government would resign. Macdonald also advised the Assembly that he considered the vote "a brusque and uncourteous insult to Her Majesty".[13][16][17][27]

Brown–Dorion government, August 2 to 5, 1858[edit]

Formation of the Brown–Dorion ministry[edit]

Governor General Head then called on Brown to form a government. Brown entered into negotiations with Dorion. In addition to the composition of the Cabinet, carefully balanced between Canada East and Canada West, Brown and Dorion needed to reach agreement on how their government would deal with the major political issues. Both made significant concessions. Dorion accepted Brown's requirement that the province shift to representation by population. In return, Brown accepted Dorion's condition that the change would be accompanied by constitutional guarantees for the French-Canadian minority, whether through a constitutional bill of rights, or a restructuring of the province along federalism lines.[3][29][30][31]

Having reached agreement on the major issues, and on the composition of the Cabinet, Brown and Dorion advised the governor general that they could form a ministry. Head appointed the new ministry on August 2, 1858. At the same time, Head cautioned Brown and Dorion that he would not guarantee a dissolution of Parliament and new elections if they lost the confidence of the Assembly, given the fluid state of the votes in the current session.[17][29][32][31]

Defeat of the ministry[edit]

The Brown–Dorion ministry faced an immediate challenge: all of the newly appointed ministers, including Brown and Dorion themselves, automatically lost their seats in the Legislative Assembly upon their appointment. The reason was that the Independence of Parliament Act provided that anyone who was appointed as a Cabinet minister vacated their seat and had to stand for re-election in ministerial by-elections. Because they had taken an office of profit under the Crown (i.e. a position with a salary paid by the government), they had to obtain the approval of their constituents. As a result, the new ministry immediately lost nine seats in the Assembly upon taking office. Brown and Dorion could watch subsequent proceedings in the Assembly, but could not take part.[3][13][32][33][34]

On August 2, the Legislative Assembly sat again. One of Dorion's supporters moved that the Assembly authorise a writ for a by-election in the constituency of Montreal, now vacant due to Dorion's appointment as a minister. One of Cartier's supporters, Hector-Louis Langevin, promptly moved an amendment, agreeing that the writ should issue, but adding that the Assembly did not have confidence in the new government. The motion of non-confidence passed by a vote of 71 to 31.[13][32][35]

Brown and Dorion then approached Governor General Head, and requested that he dissolve Parliament and order new elections, as two governments had successively been defeated on confidence matters. Head declined that request, citing the fact that there had been an election only eight months before, and that there were several significant bills still pending in the Assembly. The Brown–Dorion government then resigned, effective August 5.[3][13][17][32]

The Double Shuffle[edit]

Formation of the Cartier–Macdonald ministry, August 6, 1858[edit]

Following the resignation of the Brown–Dorion government, Governor General Head began to consider if someone else could form a government. He opened discussions with Alexander Tilloch Galt, an independent member from Canada East. Galt considered the proposal, but instead suggested the possibility of joining a government headed by Cartier. Galt entered into negotiations with Cartier, who brought in Macdonald. They were able to reach agreement on the terms for Galt to join the government: he insisted that the new government would explore the possibility of a federation of the British North American colonies, as a way to end the perpetual political instability of the Province of Canada.[36]

In addition to recruiting Galt, another factor supporting the new ministry was that the lost vote on the seat of government issue did not indicate a major loss of political support from the Bleu members generally.[37]

Based on Galt's support, Cartier and Macdonald advised the Governor General that they could form a government. The Governor General insisted that Cartier be considered the head of the government, so it was known as the Cartier–Macdonald ministry.[36]

The two Cabinet shuffles: August 6 and 7, 1858[edit]

The new ministry faced an immediate difficulty, namely the Independence of Parliament Act. If they formed a new government, would their seats automatically be vacated, as had happened with the Brown–Dorion ministry? If that occurred, the new Cartier–Macdonald ministry could lack a majority in the Assembly and might be defeated, leading to an election.

The solution that was found, likely by Macdonald, an experienced trial lawyer, was in an exception to the statutory requirement to resign. The act provided that when a member was first appointed to the Executive Council, their seat was vacated and they had to seek re-election. However, if a member held a ministerial office, and then was appointed to another ministerial position within thirty days, that member's seat was not vacated. This provision permitted Cabinet shuffles, allowing the premiers to move a minister from one Cabinet position to another one.[38][39]

Cartier and Macdonald proposed to the Governor General that the members of their former cabinet would be appointed to different Cabinet positions than the ones they had held in the Macdonald–Cartier ministry. Since they would be appointed to different positions within the thirty day period set out in the statute, Macdonald and Cartier took the position that the ministers would not lose their seats. They could then be moved back to their original positions the next day.

On August 6, the new Cartier–Macdonald ministry was appointed. All the former ministers (with three exceptions) were appointed to different positions than they had previously held. The next day, August 7, some were re-appointed to the positions they had held on August 1, before the Brown–Dorion ministry had been sworn in. For example, Cartier had been Attorney General for Canada East, and Macdonald had been Attorney General for Canada West. On August 6, Cartier was appointed Inspector General, and Macdonald was appointed Postmaster General. The next day, both were re-appointed to the Attorney General positions. Since they had all been moved to new positions within thirty days of August 1, although just for one day, and with a different government in between their appointments, they arguably came within the statutory exception for Cabinet shuffles, and did not lose their seats.[17][38]

There were three exceptions to the scheme. Cartier and Macdonald dropped William Cayley and Thomas-Jean-Jacques Loranger from Cabinet. Cayley had been the Inspector-General (equivalent to Minister of Finance), but was dropped to make room for Galt.[40] Loranger supported Montreal for the seat of government and was not a reliable vote for the government, so was not re-appointed.[41] The third exception was Narcisse-Fortunat Belleau, who was re-appointed Speaker of the Legislative Council. As an appointed member of the Legislative Council, he was not required to resign on re-appointment as Speaker.[34]

Since the Cabinet was changed twice in two days, on August 6 and August 7, it was dubbed the "Double Shuffle".[42]

Table of Cabinet positions[edit]

| Member of Cabinet | Position | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| July 29 to August 1 | August 2 to August 5 | August 6 | August 7 onwards | |

| George-Étienne Cartier | Attorney General for Lower Canada | Out of office | Inspector-General | Attorney General for Lower Canada |

| John A. Macdonald | Attorney General for Upper Canada | Out of office | Postmaster General | Attorney General for Upper Canada |

| Narcisse-Fortunat Belleau | Speaker of the Legislative Council | Out of office | Speaker of the Legislative Council | |

| Philip VanKoughnet | President of the Executive Council | Out of office | Commissioner of Crown Lands | |

| Louis-Victor Sicotte | Commissioner of Crown Lands | Out of office | Chief Commissioner of Public Works | |

| Charles Joseph Alleyn | Chief Commissioner of Public Works | Out of office | Provincial Secretary | |

| John Ross | Receiver General | Out of office | President of the Executive Council | |

| Sidney Smith | Postmaster General | Out of office | President of the Executive Council | Postmaster General |

| John Rose | Solicitor General for Lower Canada | Out of office | Receiver General | Solicitor General for Lower Canada |

| William Cayley | Inspector-General | Out of office | ||

| Thomas-Jean-Jacques Loranger | Provincial Secretary | Out of office | ||

| Alexander Tilloch Galt[a] | Not in office | Inspector General | ||

| George Sherwood[b] | Not in office | Receiver General | ||

| Source: J.O. Côté, Political Appointments and Elections in the Province of Canada, 1841 to 1860[17] | ||||

Consequences[edit]

Political implications[edit]

The immediate effect of the Double Shuffle was that the Cartier–Macdonald ministry was able to stay in power for the next three years, until defeated in the elections of 1861.

The entire episode contributed to ongoing personal distrust between Brown and Macdonald, and to strong political animosity between the different parties.[31]

The episode also shook Brown's faith in parliamentary and responsible government. He considered that Head had improperly favoured Macdonald and Cartier, agreeing to accept the Double shuffle, while rejecting his request for a dissolution and election.

More long term, both Brown and Macdonald found the perpetual partisanship of the Parliament fruitless and tiresome. Wearied by it all, both considered retiring from politics. In 1864, after another Macdonald–Cartier government fell, Brown approached Macdonald with a proposal for constitutional reform: either turn the Province of Canada into a true federation, or try to achieve a federation of all of British North America. Macdonald, Cartier and Galt took him up on the offer. The four of them created the Great Coalition that led to Canadian Confederation.

Court actions[edit]

The Double Shuffle was challenged in the courts in three separate actions, one in the Upper Canada Court of Common Pleas and two in the Upper Canada Court of Queen's Bench. The plaintiff in both cases was Allan Macdonell (also spelt McDonell), one of Brown's political allies, who sued members of the Cartier–Macdonald ministry. He argued that the exemption for reappointments in the Independence of Parliament Act did not contemplate ministers being replaced by a completely different ministry, and then members of the first ministry being reappointed.[45]

Both courts dismissed the actions. In the Court of Common Pleas, Macdonell sued all the members of the Cabinet in debt, seeking to recover the statutory penalty of £500 for each day that they remained in office illegally. The three judges of the Court of Common Pleas dismissed the action, concluding that the exception for reappointment within thirty days applied.[46]

Macdonell also sued in the Court of Queen's Bench, seeking to challenge their right to hold office, but the three judges of the Queen's Bench unanimously held that the exception did not mean that a cabinet minister had to be immediately appointed to a new position, as the plaintiff argued. They concluded that the drafters of the legislation may not have anticipated this particular situation, but the wording of the statute authorised the sequential appointment of a member of the Legislative Assembly to different Cabinet positions. The court held that it could not consider the motives of the cabinet ministers in taking the appointment, knowing that they may take a new position the next day.[47] In a companion case challenging the reappointment of an elected member of the Legislative Council, the Queen's Bench reached the same conclusion.[48]

Exploration of federation[edit]

Another result of the affair was that the new Cartier–Macdonald ministry was formally committed to explore the possibility of federation, as Galt insisted as a condition of joining the new ministry. Following the parliamentary session, a delegation consisting of Cartier, Galt and John Ross, the President of the Executive Council, travelled to Britain to sound out the British government on the idea of federation.[36]

The British government was receptive, but not prepared to invest any money in a railway connecting the Province of Canada to the Maritime provinces. Nor was it prepared to consider the federation project without an indication of interest from the Maritime provinces.

The idea of federation did not advance at that time, but the actions of the Canadian government meant that the issue had been formally raised in debates about the constitutional problems of the province of Canada.[49]

Ottawa as seat of government[edit]

The Double Shuffle episode led to the seat of government issue finally being settled. The next year, in 1859, the Cartier–Macdonald ministry reintroduced the motion for funding the construction of the parliament buildings in Ottawa. This time, the motion passed by a large majority. Construction of the new buildings began in 1860, and was completed in 1865.

The Parliament of the Province of Canada met for the last time in the new Ottawa buildings in 1866. When Canada was created in 1867, Ottawa became the seat of government of the new country, and the Parliament of Canada inherited the buildings.[26][50][51]

References[edit]

- ^ Christopher Moore, 1867 — How the Fathers Made a Deal (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1997), pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b c d e Donald Creighton, The Road to Confederation (Toronto: Macmillan Publishing, 1864; revised ed., Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 43–45.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Moore, 1867 — How the Fathers Made a Deal, pp. 12–21.

- ^ J.M.S. Careless, The Union of the Canadas: The Growth of Canadian Institutions 1841–1857 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1967), pp. 20–36, 209–210.

- ^ Careless, The Union of the Canadas, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c Paul G. Cornell, Alignment of Political Groups in Canada, 1841–67 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962 (reprinted in paperback, 2015), pp. 67–76.

- ^ Union Act, 1840, 3 & 4 Vict., c. 35 (UK), s. 12.

- ^ a b J.M.S. Careless, Brown of the Globe — The Voice of Upper Canada (Toronto: Macmillan Company of Canada Ltd., 1959), 250–251.

- ^ a b Donald Creighton, John A. Macdonald: The Young Politician (Toronto: MacMillan Company of Canada Ltd., 1952), pp. 258–259.

- ^ W.L. Morton, The Critical Years: The Union of British North America 1857–1873 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1964), pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b Cornell, Alignment of Political Groups in Canada, 1841–67, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Careless, Brown of the Globe, pp. 246–247.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Creighton, John A. Macdonald: The Young Politician, pp. 261–268.

- ^ Careless, The Union of the Canadas, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Careless, Brown of the Globe, pp. 255–256, 261-262.

- ^ a b c d Morton, The Critical Years: The Union of British North America 1857–1873, pp. 13–17.

- ^ a b c d e f J.O. Côté, Political Appointments and Elections in the Province of Canada, 1841 to 1860 (Quebec: St. Michel and Darveau, 1860), pp. 15, 65–68.

- ^ a b Careless, Brown of the Globe, pp. 251–254, 263–264.

- ^ Union Act, 1840, 3 & 4 Vict., c. 35, s. 30.

- ^ a b Creighton, John A. Macdonald: The Young Politician, pp. 247–249.

- ^ Careless, Brown of the Globe, p. 223.

- ^ James A. Gibson, "Sir Edmund Head's Memorandum on the Choice of Ottawa as the Seat of Government of Canada", Canadian Historical Review (1935), vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 411–417. [Article starts at fifth page of linked document.]

- ^ a b Wilfrid Eggleston, The Queen's Choice: A Story of Canada's Capital (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1961), pp. 98–101.

- ^ Careless, Brown of the Globe, pp. 239, 263.

- ^ Journals of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada, 3rd Session, 5th Provincial Parliament of Canada, 1857 (March 24, 1857), pp. 130–133.

- ^ a b Eggleston, The Queen's Choice, pp. 108–110.

- ^ a b Careless, Brown of the Globe, pp. 263–265.

- ^ Journals of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada, 1st Sess., 6th Provincial Parliament (July 28, 1858), p. 931.

- ^ a b James A. Gibson, "Head, Sir Edmund Walker", Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. IX (1861–1870), University of Toronto / Université Laval.

- ^ Careless, Brown of the Globe, pp. 266–269.

- ^ a b c Morton, The Critical Years: The Union of British North America 1857–1873, pp. 17–19.

- ^ a b c d Careless, Brown of the Globe, pp. 269–276.

- ^ Marc Bosc and André Gagnon (eds.), House of Commons Procedure and Practice (3rd ed., 2017), Chapter 4: The House of Commons and Its Members – Historical Perspective.

- ^ a b Act further to secure the Independence of Parliament, SProvC 1857, c. 22, s. 6.

- ^ Journals of the Legislative Assembly (August 2, 1858), pp. 935–937.

- ^ a b c Jean-Pierre Kesteman, "Galt, Sir Alexander Tilloch", Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. XII (1891–1900), University of Toronto / Université Laval.

- ^ Creighton, John A. Macdonald — The Young Politician, p. 267.

- ^ a b Creighton, John A. Macdonald: The Young Politician, p. 268.

- ^ Independence of Parliament Act, s. 7.

- ^ Paul G. Cornell, "Cayley, William", Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. XI (1881–1890), University of Toronto and Université Laval.

- ^ Jean-Charles Bonenfant, "Loranger, Thomas-Jean-Jacques", Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. XI (1881–1890), University of Toronto and Université Laval.

- ^ "Double shuffle", Oxford Reference (Oxford University Press, 2023).

- ^ Côté, Political Appointments and Elections, pp. 58, 64 note (235).

- ^ Côté, Political Appointments and Elections, pp. 56, 63 note (203).

- ^ Donald Swainson, "Macdonell (McDonell), Allan", Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. XI (1881–1890), University of Toronto / Université Laval.

- ^ Macdonell v. Macdonald (1858), 8 UCCP 479.

- ^ McDonnell v Smith (1859), 17 QBR 310..

- ^ McDonnell v Vankoughnet, (1859) 17 QBR 339.

- ^ Creighton, John A. Macdonald: The Young Politician, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Creighton, Road to Confederation, pp. 386, 388.

- ^ Constitution Act, 1867, s. 16.