Criticism of suburbia

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the English-speaking world and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (August 2022) |

Criticism of suburbia dates back to the boom of suburban development in the 1950s and critiques a culture of aspirational homeownership.[1] In the English-speaking world, this discourse is prominent in the United States and Australia being prevalent both in popular culture and academia.

In the United States[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2021) |

While the United States government has yet to define what counts as a "suburban neighborhood," more than half of Americans have described their neighborhoods as suburban.[2]

Racism[edit]

Suburbs in the United States have often been criticised for instituting explicitly racist policies to deter people deemed as other.[3]

Urban sprawl[edit]

The demand for single-family housing has led to urban sprawl in many metropolitan areas across the United States, notably in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area and the Northeast Megalopolis.

Environmental Issues[edit]

One of the major environmental problems associated with sprawl is land loss, habitat loss, and subsequent reduction in biodiversity. A review by Czech and colleagues[4] finds that urbanization endangers more species and is more geographically ubiquitous in the mainland United States than any other human activity.

Sprawl leads to increased driving, which in turn leads to vehicle emissions that contribute to air pollution and its attendant negative impacts on human health. In addition, the reduced physical activity implied by increased automobile use has negative health consequences. Sprawl significantly predicts chronic medical conditions and health-related quality of life, although it doesn't predict mental health disorders.[5] The American Journal of Public Health and the American Journal of Health Promotion, have both stated that there is a significant connection between sprawl, obesity, and hypertension.[6]

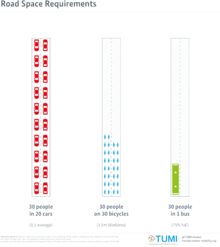

A heavy reliance on automobiles increases traffic throughout the city as well as automobile crashes, pedestrian injuries, and air pollution.[7]

Increased infrastructure/transportation costs[edit]

Living in larger, more spread out spaces generally makes public services more expensive. Since car usage becomes endemic and public transport often becomes significantly more expensive, city planners are forced to build highway and parking infrastructure, which in turn decreases taxable land and revenue, and decreases the desirability of the area adjacent to such structures.[citation needed] Providing services such as water, sewers, and electricity is also more expensive per household in less dense areas, given that sprawl increases lengths of power lines and pipes, necessitating higher maintenance costs.[8]

Residents of low-density areas spend a higher proportion of their income on transportation than residents of high density areas.[9] The unplanned nature of outward urban development is commonly linked to increased dependency on cars. In 2003, a British newspaper calculated that urban sprawl would cause an economic loss of 3905 pounds per year, per person through cars alone, based on data from the RAC estimating that the average cost of operating a car in the UK at that time was £5,000 a year, while train travel (assuming a citizen commutes every day of the year, with a ticket cost of 3 pounds) would be only £1095.[10]

In Australia[edit]

Sprawling cities define the urban Australian landscape. The iconic "quarter-acre" block is often cited as fundamental to the Australian Dream; it has both cultural and political currency.[11] In 1901, the year of Australian Federation, "almost 70 per cent of Sydney's population were living in the suburbs".[12]

There is a profound cynicism that exists in much commentary on suburbia that is promoted by "intellectuals and others seeking to delineate the suburb"[13] which has been characterised by "conformity, control and some sense of false consciousness".[14]

Suburbia bashing[edit]

Despite the fact the majority of Australians still live in the suburbs, or maybe because of it, negative discourse about suburbia, often termed "suburbia bashing", perseveres in the mainstream media.[15] Dame Edna Everage typifies this as she demonstrates both "nostalgia and disdain for the Australian suburb and suburban life".[13]

Prominent journalist Allan Ashbolt satirised the suburb that represented Australian nationalism, rooted in the post-World War II era, as passive and uninspired, inscribed strongly in spatial terms. In 1966, he described Australian reality accordingly:

"Behold the man – the Australian of today – on Sunday morning in the suburbs when the high decibel drone of the motor-mower is calling the faithful to worship. A block of land, a brick veneer, and the motor-mower beside him in the wilderness – what more does he want to sustain him."[16]

Ashbolt, among others, represent a "tradition of abuse of the suburbs and of the majority of Australians" in Australian mainstream media.[17]

Suburbia vs the Australian bush[edit]

Suburbia bashing is entrenched in questions of national identity. Disparaging commentary about the suburbs often appears in contrast to the national mythology of the Australian bush. The landscape that is portrayed in the tourism advertisements, by poets and painters, does not represent the experience of the majority of Australians. The suburb and the bush are counterposed, "the bush (cast as the authentic Australian landscape) with the city (regarded as blighted foreign import)".[18] The bush landscape is a masculine construction of a more "authentic notion of Australian national identity" exemplified by the poetry of Henry Lawson.[12] Conversely, the suburb is feminised, epitomised by Dame Edna for more than fifty years, and more recently, by comedic team Jane Turner and Gina Riley in Kath & Kim.[12]

Australian ugliness[edit]

Architect and cultural critic, Robin Boyd, also criticised suburbia, referring to it as the "Australian ugliness".[1] Boyd observed a "pursuit of respectability" in suburban spaces.[1] Boyd writes of a contrived and superficial sense of place, centered on a "fear of reality":

"The Australian ugliness begins with fear of reality, denial of the need for the everyday environment to reflect the heart of the human problem, satisfaction with veneer and cosmetic effects. It ends in betrayal of the element of love and a chill near the root of national self-respect."[19]

The ugliness that Boyd describes is qualified as "skin deep".[20] However, in the tradition of suburbia bashing, he proposes that there is an emptiness of spirit that can be read through an uninformed appreciation for aesthetics.

More recently there has been suggestion of a "new Australian ugliness".[21] New suburban developments have seen the proliferation of what have become known as "McMansions". McMansions epitomise the suburbia that is attacked by Boyd for both its monotony and "featurism"[1] Journalist Miranda Devine refers to an elitist perception that those who live in such suburban assemblages display a "poverty of spirit and a barrenness of mind" that is derived from a politics of aesthetics and taste, as expressed by Boyd fifty years ago.[15] In this "new Australian ugliness" some commentators attribute a rise in consumer culture: "There's a concern about over-consumption. But there's little thought of why – beyond advertising-driven gullibility".[21] Academic Mark Peel has rejected notions of gullible "consuming" residents of new suburbs by explaining his own "choice" to move to Melbourne's outer suburbs.[21]

Peel alludes to a discourse of suburbia that is elitist, and is based on matters of taste which have translated into a socio-cultural divide. When Miranda Devine refers to the elites, she refers to an inner-city population.[15] The divide is between the urbanites and the suburbanites, and the conflict is over national identity.

In the UK[edit]

Suburbia in the United Kingdom has been a subject of criticism for many decades, with critiques focusing on various social, cultural, and environmental aspects. The criticisms often revolve around themes such as conformity, lack of community spirit, environmental degradation, and socio-economic divides.

Historical Context[edit]

The development of suburbs in the UK accelerated during the interwar period and post-World War II era. This was driven by a combination of factors including the desire for better living conditions away from crowded urban centers, government policies promoting homeownership, and advancements in transportation that made commuting feasible.

Social Criticisms[edit]

- Conformity and Monotony: One of the most persistent criticisms is that suburban life promotes conformity and lacks diversity. George Orwell famously described suburbs as “a prison with the cells all in a row … semi-detached torture chambers.”[22] This critique suggests that suburban neighbourhoods are characterised by uniformity in housing design and lifestyle, leading to a monotonous living environment.

- Lack of Community Spirit: Critics argue that suburban areas often lack a sense of community compared to urban centres. The physical layout of suburbs—characterised by detached houses with private gardens—can lead to social isolation. Unlike urban areas where public spaces like parks, squares, and cafes facilitate social interactions, suburban design can discourage spontaneous socialising.

- Cultural Stagnation: Suburbs are often seen as culturally barren compared to cities. The absence of cultural institutions like theatres, museums, and galleries contributes to this perception. Additionally, the entertainment options available in suburbs are frequently limited to shopping malls and chain restaurants, which further reinforces the stereotype of cultural stagnation.

Environmental Criticisms[edit]

- Urban Sprawl: The expansion of suburban areas contributes significantly to urban sprawl. This phenomenon involves the spread of low-density residential development over large areas of land, leading to several environmental issues such as habitat destruction and loss of agricultural land.

- Increased Car Dependency: Suburban living often necessitates car ownership due to inadequate public transportation options. This reliance on automobiles leads to increased traffic congestion, higher greenhouse gas emissions, and air pollution. The environmental footprint per capita is generally higher in suburban areas compared to urban centres.

- Infrastructure Strain: Providing infrastructure services such as water supply, sewage systems, electricity, and road maintenance becomes more challenging and expensive in sprawling suburban areas compared to denser urban environments.

Economic Criticisms[edit]

- Economic Inefficiency: The dispersed nature of suburban development can lead to economic inefficiencies. For instance, maintaining extensive road networks and utility lines for sparsely populated areas incurs higher costs per household than in densely populated urban settings.

- Negative Equity Risks: During economic downturns or housing market crashes, suburban homeowners may face higher risks of negative equity (owing more on their mortgage than their home is worth) compared to those living in city centres where property values tend to be more stable.

Cultural Criticisms[edit]

- Suburbia Bashing: In popular culture and media discourse within the UK, there has been a trend known as “suburbia bashing.” This involves portraying suburban life negatively as dull or uninspired. Prominent figures like journalist Allan Ashbolt have satirized suburbia for its perceived passivity and lack of dynamism.[23]

- Nostalgia vs Disdain: Figures like Dame Edna Everage have encapsulated both nostalgia for traditional suburban life while simultaneously expressing disdain for its perceived limitations.

See also[edit]

- The 'Burbs

- Home ownership in Australia

- Home-ownership in the United States

- White flight § Government-aided white flight

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Boyd (1960).

- ^ "US Is Majority Suburban but Doesn't Define Suburb". Bloomberg. 14 November 2018.

- ^ Adams (2006), pp. 601–602.

- ^ Czech, Brian; Krausman, Paul R .; Devers, Patrick K. (2000). "Economic Associations among Causes of Species Endangerment in the United States". BioScience. 50 (7): 593. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0593:EAACOS]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Sturm, R.; Cohen, D.A. (October 2004). "Suburban sprawl and physical and mental health". Public Health. 118 (7): 488–496. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2004.02.007. PMID 15351221.

- ^ McKee, Bradford. "As Suburbs Grow, So Do Waistlines Archived August 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine", The New York Times, September 4, 2003. Retrieved on February 7, 2008.

- ^ De Ridder, K (2008). "Simulating the impact of urban sprawl on air quality and population exposure in the German Ruhr area. Part_II_Development_and_evaluation_of_an_urban_growth_scenario". Atmospheric Environment. 42 (30): 7070–7077. Bibcode:2008AtmEn..42.7070D. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.06.044. S2CID 95045241.

- ^ Snyder, Ken; Bird, Lori (1998). Paying the Costs of Sprawl: Using Fair-Share Costing to Control Sprawl (PDF). Washington: U.S. Department of Energy's Center of Excellence for Sustainable Development. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ McCann, Barbara. Driven to Spend Archived June 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Surface Transportation Policy Project (2000). Retrieved on February 8, 2008.

- ^ "Is your car worth it?", The Guardian, Guardian Media Group, February 15, 2003. Retrieved on February 8, 2008.

- ^ Horin (2005).

- ^ a b c Turnball (2008), pp. 15–32.

- ^ a b Healy (1994).

- ^ Simons (2005), p. 28.

- ^ a b c Devine (2004).

- ^ Ashbolt (1966), p. 353.

- ^ Simons (2005), pp. 11–36.

- ^ Gleeson (2006).

- ^ Boyd (1960), p. 225.

- ^ Boyd (1960), p. 1.

- ^ a b c Peel (2007).

- ^ Huq, Rupa (16 November 2009). "Suburbia: the new utopia?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ Jackson, James (5 June 2024). "Still sneering at the suburbs? That's passé now". www.thetimes.com. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

Bibliography[edit]

- Adams, L. J. (1 September 2006). "Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism". Journal of American History. 93 (2): 601–602. doi:10.2307/4486372. ISSN 0021-8723. JSTOR 4486372.

- Ashbolt, Allan (December 1966). "Godzone 3: Myth and Reality". Meanjin Quarterly. 25 (4): 353.

- Boyd, Robin (1960). The Australian Ugliness. Melbourne: Penguin Books.

- Devine, Miranda (24 October 2004). "Copping the bile in Kellyville". The Sun-Herald.

- Gleeson, Brendan (2006). The Australian Heartlands: Making Space for Hope in the Suburbs. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

- Healy, Chris (1994). "xv". In Ferber, Sarah; Healy, Chris; McAuliffe, Chris (eds.). Beasts of Suburbia: Reinterpreting Cultures in Australian Suburbs. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Horin, Adele (4 August 2005). "The end of the mythical quarter-acre block". The Age.

- Peel, Mark (16 September 2007). "McMansions: The inside story of life on the outer". The Age.

- Simons, Margaret (2005). Schultz, Julianne (ed.). "Ties that Bind". Griffith Review: People Like Us. 8, Winter: 11–36.

- Turnball, Sue (2008). "Mapping the Vast Suburban Tundra: Australian comedy from Dame Edna to Kath and Kim". International Journal of Cultural Studies. 11 (1): 15–32. doi:10.1177/1367877907086390. S2CID 146717661.