Florianopolitan dialect

| Florianopolitan dialect | |

|---|---|

| manezês, manezinho | |

A view of Ribeirão da Ilha, an Azorean settlement in Florianópolis, where Florianopolitan dialect is traditionally spoken. | |

| Region | Florianópolis |

| Ethnicity | Azorean Brazilians |

Early form | |

| Portuguese alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

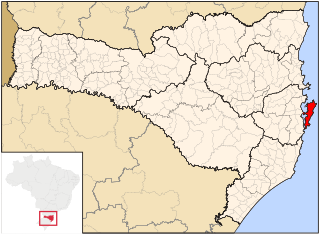

Florianópolis in Santa Catarina (state), Brazil. | |

Florianopolitan dialect, informally called manezês or manezinho,[1] is a variety of Brazilian Portuguese heavily influenced by (and often considered an extension of) the Azorean dialect.[2][3][4] It is spoken by inhabitants of Florianópolis (the capital of Santa Catarina state) of full or predominant Azorean descent[5][6] and in cities near the capital but with slight variations.[5] The dialect was originally brought by immigrants from Azores who founded several settlements in the Santa Catarina island from the 18th century onwards. The isolation of their settlements[7] made Florianopolitan differ significantly from both Standard European and Brazilian Portuguese.[8]

Once widely spoken in the Santa Catarina island, the Florianopolitan dialect is now almost restricted to the traditional Azorean settlements, and the standard Brazilian Portuguese became the predominant variant for the island inhabitants, many of which come from other parts of Santa Catarina state, other Brazilian states, or even other countries.[9]

Phonology[edit]

Florianopolitan is not a uniform dialect, and there are many variations, depending on the community and generation of the speaker. However, here are several principal characteristics of the Florianopolitan dialect speech:

- An 's' is often pronounced [ʃ] before a 'c', 'p', 'qu', or 'e'. It is also pronounced [ʃ] at the end of a word, very softly. The phrase as festas (the parties) is thus pronounced [ɐʃˈfɛʃtɐʃ] or [ɐʃˈfɛʃtɐ].

- An 's', before a 'd', 'm' or 'n', is pronounced [ʒ]. Thus, mesma (same) is pronounced [ˈmɛʒmɐ].

- /t/ and /d/ are pronounced respectively as [t] and [d] even before /i/. In most of Southeastern Brazil, they are affricates [tʃ] and [dʒ].

- Both word-initial and preconsonantal /ʁ/ are glottal [h], but there is some variation. Some speakers, the older generations, use an alveolar trill [r], as in Spanish, Galician, old varieties and some rural developments of European Portuguese, and some other Southern Brazilian Portuguese dialects. Others pronounce it as a uvular trill [ʀ] or a voiceless dorsal fricative, velar [x] or uvular [χ].

- As in Caipira dialects and most speakers of Fluminense dialect, word-final /ʁ/ is deleted unless the next word is without a pause and starts with a vowel.

Forms of address[edit]

The Florianopolitan dialect retains forms of address that are obsolete elsewhere in Brazil.

Tu is used, along with its corresponding verb forms, to address people of the same or lesser age, social or professional status, or to show intimacy, as between relatives or friends. "Você" is reserved for outsiders or to people of lesser status to stress lack of intimacy. Usage is obsolete in most of Brazil but is not exclusive to Florianópolis.

O senhor/A senhora is used to address people of a greater age or status or to preserve a respectful distance. In many families, children (especially adult children) address their parents this way (Standard Portuguese, used in all of Brazil).

Indirect third-person address can be used for those of an intermediate status, especially if one wants to be affectionate or welcoming. A solicitous grandchild might ask, "A avó quer mais café?" A respectful student could say, "O professor pode repetir a pergunta?" A 30-year-old man entering a shop for the first time will be greeted, "Que queria o moço?" (in European Portuguese).

Vocabulary[edit]

| Florianopolitan dialect | Standard Portuguese | English | Usage | Examples | Notes |

| A três por dois | Com demasiada freqüencia | Too often | Ele vem à minha casa a três por dois – He comes to my home too often | Literally "at three for two". Widespread in Brazil but not typical of Florianópolis. | |

| Acachapado | Muito triste, deprimido | Very sad, depressed | "Triste", "deprimido" are the usual words in Florianópolis. | Widespread in at least Southern Brazil but not typical of Florianópolis. | |

| Antanho | Antigamente | Of old | "Antigamente" is the usual word in Florianópolis. | In most of Brazil, it is considered archaic or bookish. | |

| Bispar | Espiar | To spy | "Espiar" is the usual word in Florianópolis. | In most of Brazil, it means "to understand" or "to grasp." | |

| Cabreiro | Desconfiado | Distrustful | "Desconfiado" is the usual word in Florianópolis. | Used only in a colloquial register. | Widespread in Brazil but not typical of Florianópolis. |

| Na casa do chapéu | Muito longe | Very far (away) | Literally "in the house of the hat." Used only in colloquial register for (sometimes humorous) emphasis. "Muito longe" is the usual wording in Florianópolis. | Essa loja fica na casa do chapéu – This shop is really far away | Widespread in Brazil but not typical of Florianópolis. |

| Esculacho | Repreensão | Rebuke | Used only in a colloquial register. | Widespread in at least Southern Brazil but not typical of Florianópolis. | |

| Gervão | Lagarta | Caterpillar | |||

| Mal de bitaca | Sem dinheiro | Broke (without money) | Actually a local slang. | Estou muito mal de bitaca – I am really quite broke. | |

| Rapariga | Rapariga (feminine form of "rapaz") | Teenage girl, young adult woman | Standard Portuguese but, in other parts of Brazil, archaic or, especially in the popular or colloquial registers, may stand for "prostitute." |

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Lima, Ronaldo; Souza, Ana Cláudia de (2005). "Flutuação de sentido: um estudo na Ilha de Santa Catarina" [Fluctuation of Meaning: A Study on the Island of Santa Catarina]. Revista Philologus (in Portuguese). 11 (33).

- ^ "I Congresso Internacional de Gestão de Tecnologia e Sistemas de Informação: Florianópolis" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2011-07-06.

- ^ Nascimento, Leila Procópia do; Guimarães, Valeska Nahas (2019). "Reestruturação econômica e suas implicações no trabalho e na educação: relações de gênero em contexto" [Economic Restructuring and Its Implications for Work and Education: Gender Relations in Context]. Revista Trabalho Necessário. 7 (9). doi:10.22409/tn.7i9.p6098.

- ^ Haupt, Carine (2007). Sibilantes coronais – o processo de palatalização e a ditongação em sílabas travadas na fala de florianopolitanos nativos: uma análise baseada na fonologia da geometria de traços [Coronal Sibilants – the Palatalization Process and Diphthongization in Syllables Caught in the Speech of Native Florianopolitans: An Analysis Based on the Phonology of Trace Geometry] (PDF) (master's thesis) (in Portuguese). Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina.

- ^ a b Monguilhott, Isabel de Oliveira e Silva (2007). "A variação na vibrante Florianopolitana: um estudo sócio-geolingüístico" [Variation in Vibrant Florianopolitana: A Socio-Geolinguistic Study] (PDF). Revista da ABRALIN (in Portuguese). 6 (1): 147–169. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-24.

- ^ Görski, Edair Maria; Coelho, Izete Lehmkuhl (2009). "Variação linguística e ensino de Gramática" [Linguistic Variation and Grammar Teaching]. Working Papers em Linguística (in Portuguese). 10 (1): 73–91. doi:10.5007/1984-8420.2009v10n1p73.

- ^ Muniz, Yara Costa Netto (2008). Comunidades semi-isoladas fundadas por Açorianos na Ilha de Santa Catarina [Semi-Isolated Communities Founded by Azoreans on Santa Catarina Island] (doctor's thesis) (in Portuguese). Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto. Archived from the original on 2012-09-09.

- ^ Rogers, Francis Millet (1947). "Brazil and the Azores". Modern Language Notes. 62 (6): 361–370. doi:10.2307/2909270. JSTOR 2909270.

- ^ Peluso Júnior, Victor Antônio, O crescimento populacional de Florianópolis e suas repercussões no plano e na estrutura da cidade [The Population Growth of Florianópolis and Its Repercussions on the Plan and Structure of the City] (PDF) (in Portuguese), archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06