Abu Salabikh

| Location | Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 32°16′00″N 45°05′00″E / 32.26667°N 45.08333°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | Early Uruk period |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1963-65, 1975–90 |

| Archaeologists | Donald P. Hansen, Nicholas Postgate |

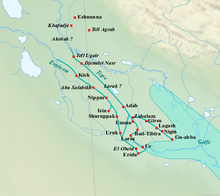

The archaeological site of Abu Salabikh (Tell Abū Ṣalābīkh), around 20 km (12 mi) northwest of the site of ancient Nippur and about 150 kilometers southeast of the modern city of Baghdad in Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq marks the site of a small Sumerian city that existed from the Neolithic through the late 3rd millennium, with cultural connections to the cities of Kish, Mari and Ebla.[1][2][3] Its ancient name is unknown though Eresh and Kesh have been suggested as well as Gišgi.[4][5] Kesh was suggested by Thorkild Jacobsen before excavations began.[6] The Euphrates was the city's highway and lifeline; when it shifted its old bed (which was identified to the west of the Main Mound by coring techniques), in the late third millennium BC, the city dwindled away. Only eroded traces remain on the site's surface of habitation after the Early Dynastic Period.[7] There is another small archaeological site named Abu-Salabikh in the Hammar Lake region of Southern Iraq, which has been suggested as the possible capital of the Sealand dynasty.[8]

History[edit]

Although signs of occupation at the site date back to the Neolithic period, primary occupation occurred during the Uruk period in the Late Chalcolithic and then in the Jemdat Nasr and Early Dynastic periods in the Early Bronze Age. An examination of the smaller outlying sites nearby showed there was also occupation in the Kassite, Sassanian, Seleucid, and Parthian periods in the area.[9]

Archaeology[edit]

The site consists of three mounds with an overall extent of roughly 900 meters by 850 meters. To the east is the 12 hectare wall enclosed Main (Early Dynastic) mound. To the west, on the other side of the bed of an ancient canal or watercourse, is the 10 hectare Uruk and Jemdet Nasr mound to the north and the 8 hectare South mound with its Early Dynastic palace to the south. The full Early dynastic extent, with outer margins now under alluvial deposits, is estimated at 50 hectares.[10]

Abu Salabikh was excavated by an American expedition from the Oriental Institute of Chicago led by Donald P. Hansen in 1963 and 1965 for a total of 8 weeks. They found the site, lying in a salt bog, had numerous robber holes. Unlike the nearby site of Nippur which continued to be occupied for millennia, at Abu Salabikh the Early Dynastic remains were near the surface. The expedition found around 500 tablets and fragments, containing some of the earliest ancient literature.[7][11][12] A number of animal remains were also found including domestic dog, lion, equid, pig, cattle, gazelle, caprines (sheep and goat), and antelope.[13] Remains of various birds were also found.[14]

Between 1975 and 1990 Abu Salabikh was excavated by a British School of Archaeology in Iraq team under the direction of Nicholas Postgate.[15][16][17] Excavations were suspended in 1990 with the Invasion of Kuwait and have not been resumed. The city, built on a rectilinear plan in the early Uruk period, revealed a small but important repertory of cuneiform texts on some 500 tablets, of which the originals were stored in the Iraq Museum, Baghdad.[5] Texts, comparable in date and content with texts from Shuruppak (modern Fara, Iraq) included school texts, literary texts, word lists, and some administrative archives, as well as the Instructions of Shuruppak, a well-known Sumerian "wisdom' text of which the Abu Salabikh tablet is the oldest copy.[18] While the writing remained Sumerian, Semitic scribal names became more common as the Early Dynastic period wore on.[19][20] The archaic form of Sumerian in the texts is not fully understood however a number of literary compositions were found that had beforehand been thought to have not existed until half a millennium later in the Old Babylonian period.[6][21] Originally it was thought that the tablet. contemporary with the ones found at Fara were dated to the period of Early Dynastic III ruler of First dynasty of Lagash Ur-Nanshe (c. 2500 BC). Subsequent study pushed the dating to a century before Ur-Nanshe though it has also been suggested that the dating was after Ur-Nanshe though before Eannatum of Lagash, his grandson. This is still an open issue.[22]

On the Uruk mound, which was abandoned after the Jemdet Nasr period, 1650 high fired clay sickles were found.[23] Two grain samples from the Middle Uruk layer of the Uruk Mound were accelerator radiocarbon dated with calibrated dates of 3520 ± 130 BC.[24] Calibration was based on that of Pearson.[25]

Seventy four Neolithic clay accounting tokens were found at the site.[26] Over one hundred pottery shards that had been filed into 3 centimeter discs and pierced were found, suggested as for use in abacus type counting devices.[27]

Eresh[edit]

The city of Eresh (eréški) is known from the Early Dynastic, through the Akkadian perod into the Ur III period and then apparently disappears from history though a year name of Sin-Muballit (c. 1813-1792 BC) is "Year Sin-muballity built the city wall of Eresz". Its location is unknown though earlier Uruk was proposed and more recently Abu-Salabikh and Jarin.[28][29] One tablet found at Abu Salabikh (IAS 505) did mention workers belonging to a "King of Eresh".[5] Its city-god was Nisaba, whose cult site was later moved to Nippur.[30] Eresh appears on an Early Dynastic geographical list.[31] It is known that during the reign of the second Ur III Empire ruler Shulgi there was a governor of Eresh named Ea-Bani and one named Ur-Ninmug, and under Amar-Sin one named Ur-Baba.[32][33] In the Ur III period there was a shrine to the goddess Annunitum at Eresh.[34]

Enheduanna, daughter of Sargon of Akkad, the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire wrote 42 temple hymns, including one to E-Zagin, the temple of Nisaba in Eresh which survives in fragmentary form.

"House of Stars. House of Lapis Lazuli, sparkling bright, you open the way to all the lands ... are set in the shrine. Eresh. Each month, the ancient lords raise their head for you. On the hill, soap ... The great goddess Nisaba has brought the great powers from heaven, adding to your powers ... Righteous woman of unmatched mind. Soothing ... and opening her mouth,consulting a tablet of lapis lazuli, giving guidance to all the lands. Righteous woman, cleansing soap, born to the upright stylus. She measures the heavens and outlines the earth:All praise Nisaba."[35]

In the Sumerian literary composition Enmerkar and En-suhgir-ana, a sorcerer, Urgirinuna, goes to Eresh and makes all the cows and goats stop giving milk.[36][37]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Moorey, P. R. S. (1981). "Abu Salabikh, Kish, Mari and Ebla: Mid-Third Millennium Archaeological Interconnections". American Journal of Archaeology. 85 (4): 447–448. doi:10.2307/504868. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 504868. S2CID 191401637.

- ^ Pettinato, G., "L’Atlante Geografico Del Vicino Oriente Antico Attestato Ad Ebla e Ad Abū Şalābīkh (I)", Orientalia, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 50–73, 1978

- ^ Pomponio, Francesco, "Notes on the Lexical Texts from Abū Salābīkh and Ebla", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 285–90, 1983

- ^ Cohen, Mark E., “The Name Nintinugga with a Note on the Possible Identification of Tell Abu Salābīkh", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 82–92, 1976

- ^ a b c M. Krebernik and J. N. Postgate, "The tablets from Abu Salabikh and their provenance", Iraq, vol. 71, pp. 1- 32, 2009

- ^ a b Biggs, Robert D., "An Archaic Sumerian Version of the Kesh Temple Hymn from Tell Abū Ṣalābīkh", vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 193-207, 1971

- ^ a b Biggs, Robert D. (1974). Inscriptions from Tell Abū Ṣalābīkh (PDF). Donald P. Hansen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-62202-9. OCLC 1170564.

- ^ Roux, G., "Recently Discovered Ancient Sites in the Hammar Lake District-Southern Iraq", Sumer, XVI, no. 1-2, pp. 20-31, 1960

- ^ Wilkinson, T. J., "Early Channels and Landscape Development around Abu Salabikh, a Preliminary Report", Iraq, vol. 52, pp. 75–83, 1990

- ^ Colantoni, Carlo, "Are We Any Closer to Establishing How Many Sumerians per Hectare? Recent Approaches to Understanding the Spatial Dynamics of Populations in Ancient Mesopotamian Cities", At the Dawn of History: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of J. N. Postgate, edited by Yağmur Heffron, Adam Stone and Martin Worthington, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 95-118, 2017

- ^ Alster, Bendt, "Early Dynastic Proverbs and Other Contributions to the Study of Literary Texts From Abū Ṣalābīkh", Archiv Für Orientforschung, vol. 38/39, pp. 1–51, 1991

- ^ [1] Alberti, A., "A Reconstruction of the Abu Salabikh God-list", Studi Epigraphici e linguistici sul Vicino Oriente 2, pp. 3–23, 1985

- ^ Clutton-Brock, Juliet, and Richard Burleigh, "The Animal Remains from Abu Salabikh: Preliminary Report", Iraq, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 89–100, 1978

- ^ Eastham, Anne, "The bird bones from Abu Salabikh", Iraq, vol. 71, pp. 99–114, 2009

- ^ Nicholas Postgate, "Excavations at Abu Salabikh 1976", Iraq, vol. 39, pp. 269–299, 1977

- ^ Nicholas Postgate, "Excavations at Abu Salabikh 1977", Iraq, vol. 40, pp. 89-100, 1978

- ^ Nicholas Postgate, "Excavations at Abu Salabikh 1978-79", Iraq, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 87–104, 1980

- ^ Krebernik, Manfred, "Die Texte aus Fara und Tell Abu Salabikh", In Mesopotamien: Späturuk-Zeit und Frühdynastische Zeit, ed. P. Attinger and M. Wäfler, Annäher-ungen 1. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 160. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 237-427, 1998

- ^ Biggs, R. D., "The Semitic Personal Names from Abu Salabikh and the Personal Names from Ebla", in Eblaite Personal Names and Semitic Name-giving, ed. A. Archi, ARES 1. Rome: Missione Archeologica Italiana in Siria, pp.89–98, 1988

- ^ Biggs, Robert D., "Semitic Names in the Fara Period", Orientalia, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 55–66, 1967

- ^ [2] Nicholas Postgate, "Abu Salabikh", in J. Curtis, ed., Fifty Years of Mesopotamian Discovery, London, pp. 48–61, 1982

- ^ Hallo, William W., "The Date of the Fara Period A Case Study in the Historiography of Early Mesopotamia", Orientalia, vol. 42, pp. 228–38, 1973

- ^ [3] Benco, Nancy L., "Manufacture and Use of Clay Sickles from the Uruk Mound, Abu Salabikh, Iraq", Paléorient, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 119–34, 1992

- ^ Susan Pollock, Caroline Steele and Melody Pope, "Investigations on the Uruk Mound, Abu Salabikh, 1990", Iraq, vol. 53, pp. 59–68, 1991

- ^ Pearson, G. W. et al., "High precision 14C measurement of Irish oaks to show the natural 14C variation from a.d. 1840 to 5210 b.c.", Radiocarbon 28, pp. 911-34, 1986

- ^ Overmann, Karenleigh A., "The Neolithic Clay Tokens", The Material Origin of Numbers: Insights from the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press, pp. 157-178, 2019

- ^ Woods, Christopher, "The Abacus in Mesopotamia: Considerations from a Comparative Perspective", The First Ninety Years: A Sumerian Celebration in Honor of Miguel Civil, edited by Lluís Feliu, Fumi Karahashi and Gonzalo Rubio, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 416-478, 2017

- ^ [4] Matthews, R. and Matthews, W., "A palace for the king of Eres? Evidence from the Early Dynastic City of Abu Salabikh, south Iraq" In: Heffron, Y., Stone, A. and Worthington, M. (eds.) At the dawn of history. Ancient Near Eastern studies in honour of J. N. Postgate. Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake, pp. 359–367, 2017 ISBN 9781575064710

- ^ Postgate, J. N., and Moorey, P. R. S., "Excavations at Abu Salabikh, 1975", Iraq, vol. 38, pp. 133–69, 1976

- ^ Michalowski, P., "Nisaba. A. Philologisch", in vol. 9 of Reallexikon der Assyriologie. Edited by D. O. Edzard. 10 vols. Berlin: W. de Gruyter, pp. 575–79, 2001

- ^ D.R. Frayne, "The Early Dynastic List of Geographical Names", AOS 74, New Haven, 1992

- ^ Frayne, Douglas, "Table III: List of Ur III Period Governors", Ur III Period (2112-2004 BC), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. xli-xliv, 1997

- ^ Sharlach, T. M., "An Ox of One’s Own: Provisioners and Influence", An Ox of One's Own: Royal Wives and Religion at the Court of the Third Dynasty of Ur, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 211-238, 2017

- ^ Sharlach, T. M., "Belet-šuhnir and Belet-terraban and Religious Activities of the Queen and the Concubine(s)", An Ox of One's Own: Royal Wives and Religion at the Court of the Third Dynasty of Ur, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 261-286, 2017

- ^ Helle, Sophus, "The Temple Hymns", Enheduana: The Complete Poems of the World's First Author, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 53-94, 2023

- ^ Attinger, P., "Remarques a Propos de la 'Malédiction d'Accad'", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 78, no. 2, pp. 99–121, 1984

- ^ Michalowski, Piotr, "Maybe Epic: the origins and reception of Sumerian heroic poetry". Epic and History, pp. 7-25, 2010

Further reading[edit]

- Robert D. Biggs, "The Abu Salabikh Tablets. A Preliminary Survey", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 73–88, 1966

- Biggs, Robert D., "Ebla and Abu Salabikh: The Linguistic and Literary Aspects", in La lingua di Ebla: Atti del convegno internazionale (Napoli, 21–23 aprile 1980), Edited by Luigi Cagni, Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale, pp. 121–33, 1981

- Biggs, R. D. and Postgate, J. N., "Inscriptions from Abu Salabikh, 1975", Iraq 40, pp. 101–117, 1978

- Crawford, Harriet E. W., "Some fire installations from Abu Salabikh, Iraq (Dedicated to the Memory of Margaret Munn-Rankin)", Paléorient, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 105–14, 1981

- Crawford, H. E. W., "More Fire Installations from Abu Salabikh", Iraq, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 32–34, 1983

- Angela von den Driesch, "Fischknochen Aus Abu Salabikh/Iraq", Iraq, vol. 48, pp. 31–38, 1986

- Edzard, D. O., "Fara und Abu Salabih. Die 'Wirtschaftstexte'", ZA 66, pp. 156–195, 1976

- [5] Jones, Jennifer E., "Standardized Volumes? Mass-Produced Bowls of the Jemdet Nasr Period from Abu Salabikh, Iraq", Paléorient, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 153–60, 1996

- Manfred Krebernik and Jan J. W. Lisman, "The Sumerian Zame Hymns from Tell Abū Ṣalābīḫ With an Appendix on the Early Dynastic Colophons", dubsar 12, 2020 ISBN 978-3-96327-034-5

- Moon, Jane, "Some New Early Dynastic Pottery from Abu Salabikh", Iraq, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 47–75, 1981

- Payne, Joan Crowfoot, "An Early Dynastic III Flint Industry from Abu Salabikh", Iraq, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 105–19, 1980

- [6] Pollock, S., "Political Economy as viewed from the Garbage Dump : Jemdet Nasr Occupation at the Uruk Mound, Abu Salabikh", Paléorient, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 57–75, 1990

- Pollock, Susan, "Making Fire in Uruk-Period Abu Salabikh", At the Dawn of History: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of J. N. Postgate, edited by Yağmur Heffron, Adam Stone and Martin Worthington, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 413–422, 2017

- Pomponio, F., "I nomi personali dei testi amministrativi die Abu Sal?bih", Studi Epigrafici e Linguistici sul Vicino Oriente Antico 8, pp. 141–147, 1991

- Pope, Melody, "Remembrances from the Field – Excavating at Abu Salabikh with Susan Pollock. A Photo Essay", Pearls, Politics and Pistachios. Essays in Anthropology and Memories on the Occasion of Susan Pollock's 65th Birthday, hrsg. v. Aydin Abar, pp. 203–218, 2021

- Nicholas Postgate and J.A. Moon, "Excavations at Abu Salabikh 1981", Iraq, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 103–136, 1982

- Nicholas Postgate, "Excavations at Abu Salabikh 1983", Iraq, vol. 46, pp. 95–114, 1984

- Postgate, J. N. - Killick, J. A., "British Archaeological Expedition to Abu Salabikh, Final Field Report on the 8th Season", Sumer, vol. 39, pp. 95–99, 1983

- Postgate, John Nicholas, "City of Culture 2600 BC: Early Mesopotamian History and Archaeology at Abu Salabikh", Archaeopress Publishing Ltd, 2024 ISBN 9781803276700

- R.J. Matthews and Nicholas Postgate, "Excavations at Abu Salabikh 1985-86", Iraq, vol. 49, pp. 91–120, 1987

- Nicholas Postgate, "Excavations at Abu Salabikh 1988-89", Iraq, vol. 52, pp. 95–106, 1990

- S. Pollock, M. Pope and C. Coursey, "Household Production at the Uruk Mound, Abu Salabikh, Iraq", American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 100, no. 4, pp. 683–698, 1996

- Nicholas Postgate, "Early Dynastic burial customs at Abu Salabikh", in Sumer 36, pp. 65–82, 1980

- Postgate J.N. and Moon J.A., "Excavations at Abu Salabikh, a Sumerian city", National Geographic Research Reports: 1976 projects, vol. 17, pp. 721–743, 1984

- [7] Unger-Hamilton, Romana, et al., "Drill bits from Abu Salabikh, Iraq", MOM Éditions 15.1, pp. 269–285, 1987

- Wencel, M., "ABU SALABIKH – ABSOLUTE RADIOCARBON CHRONOLOGY.", Iraq, vol. 83, pp. 245–258, 2021 doi:10.1017/irq.2021.7

- Abu Salabikh Excavations:

- Volume I - J.N. Postgate, "The West Mound Surface Clearance",Oxbow Books, 1983 ISBN 0903472066 PDF [8]

- Volume II - H.P. Martin, J. Moon & J.N. Postgate, "Graves 1 to 99", Oxbow Books, 1985 ISBN 9780903472098 PDF [9]

- Volume III - Jane Moon, "Catalogue of Early Dynastic Pottery", Oxbow Books, 1987 ISBN 9780903472111 PDF [10]

- Volume IV - A.N. Green, "The 6G Ash-Tip and its Contents: Cultic and Administrative Discard from the Temple?", Oxbow Books, 1993 ISBN 9780903472135 PDF [11]

External links[edit]

- Oriental Institute Annual Reports 1964-1965 - The Soundings At Tell Abu Salabikh

- Oriental Institute Annual Reports 1965-1966 - Tablets from Tell Abu Salabikh

- Oriental Institute Annual Reports 1967-1968 - Tablets from Tell Abu Salabikh

- Oriental Institute Annual Reports 1971-1972 - Tablets from Tell Abu Salabikh

- Oriental Institute Annual Reports 1972-1973 - Tell Abu Salabikh

- Digital tables from Abu Salabikh at CDLI

- Site photographs from Oriental Institute Archived 2014-01-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Populated places established in the 3rd millennium BC

- Populated places disestablished in the 3rd millennium BC

- History of Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate

- Archaeological sites in Iraq

- Sumerian cities

- Former populated places in Iraq

- Tells (archaeology)

- Kish civilization

- Early Dynastic Period (Mesopotamia)

- Uruk period